Many of us recognise that rather striking modernist building in Cromwell Gardens near South Kensington tube, having seen it on the way to the V&A or perhaps a Prom at the Albert Hall but not been sure what it is exactly. I hadn't actually been inside until last week when I was given a guided tour. The space was discussed at one point as a potential site for the National Theatre. It’s actually the Ismaili Centre, the first of six throughout the world (pictured below, the latest in Toronto) and was built by the Casson Cander Partnership and opened (by Margaret Thatcher and the spiritual leader of the Ismailis, the Aga Khan) in 1985.

The design has stood up well, and its mix of sleek modern lines and the sacred geometry of Islam says a lot about the Ismailis themselves, adeptly mixing tradition and modernity as they do. The space is primarily a religious and community centre, but has numerous exhibits, talks and concerts that are open to the general public.

The Ismailis are, it is fair to say, a more tolerant branch of Islam than the more head-banging fundamentalists that so often feature in the media. I became interested in them in particular on a trip a few years ago to Central Asia, an area where there are a lot of Ismailis, and the Aga Khan’s Development Network with its Music Initiative was doing some of the most impressive work in developing and sustaining music in the region. They support older musicians and pay them to teach younger ones, and have put on tours to showcase different musical forms from this most enigmatic place.

Central Asia is huge – Kazakhstan on its own is bigger than Western Europe and the ninth largest country in the world – and the culture of the Stans is almost entirely unknown outside the vast steppes. The fast-changing region is also arguably a key to how large chunks of the world may develop: there are the forces of oligarchy and despotism – and those struggling for democracy opposing them – as well as thrusting capitalism, all within an Islamic framework.

Central Asia is huge – Kazakhstan on its own is bigger than Western Europe and the ninth largest country in the world – and the culture of the Stans is almost entirely unknown outside the vast steppes. The fast-changing region is also arguably a key to how large chunks of the world may develop: there are the forces of oligarchy and despotism – and those struggling for democracy opposing them – as well as thrusting capitalism, all within an Islamic framework.

The first group I met in Central Asia were some hours north of Bishkek, the surprisingly cosmopolitan capital of Kyrgyzstan. The group's leader, Nurlanbek Nyashanov, described his group Tengir-Too as "a new ensemble that plays old music" and indeed this is music that is hundreds of years old, rhythmically sophisticated with an appealing countryish twang. It's played on rare instruments such as the three-stringed komuz or the archaic qyl qiyak, which is made of horsehair and apricot wood. Some musicologists believe it to be the forerunner of the European violin.

Such instruments are easily portable and it is likely that a version of this music was once played at the court of Genghis Khan after a hard day's conquering and pillaging (although someone tried to convince me that Genghis Khan had got a bad press and wasn't nearly as bad as he has been portrayed). Anyway, Tengir-Too are the closest thing anyone is ever likely to hear to Genghis's house band, and “what could be more rock'n'roll than that?” Tengir-Too were one of the groups that played a memorable Concert at the Coliseum in 2004. The cultural influence of communism and the former Soviet Union was not entirely bad – the large choirs in places like Bulgaria (made famous on the unlikely bestseller Les Mystères Des Voix Bulgares) were Soviet concoctions, disciplining raw folk music in a thrilling and beguiling way.

But the Soviets distrusted Islamic or shamanistic cultures and suppressed much of the indigenous music of this part of the world. The Aga Khan’s Development Network has sprung into action to help out with the ongoing post-Soviet economic and humanitarian crisis. Their considerable resources, with funds from ordinary Ismailis, have helped to fund the new University of Central Asia, its campus spread over three remote sites in Tajikistan, Krygyzstan and Kazakhstan. The Music Initiative is a branch of their activities, seeing culture and music as an essential part of development.

He dug out a cassette tape of a mugam singer, recorded nearly a century ago. The sheer passion of the music broke through the veils of time

Musicians who kept traditions alive in secret in the Soviet era have been beneficiaries of the Aga Khan’s Music Initiative, such as Alim Qasimov from Azerbaijan. When I met him at his charming but modest flat in downtown Baku, he dug out a cassette tape of a mugam singer, Mashadi Fazzaliyev, recorded nearly a century ago. The sheer passion of the music broke through the veils of time and poor recording quality. Qasimov said that one day he hoped to emulate the power of the music we heard. In a sense, the Soviet occupation caused a break in a tradition to which he is intuitively reconnecting himself.

One of the most important older forms is the shashmaqam, which I caught in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, music of great refinement and profound beauty. This was tolerated to some extent by the Soviets, but only as a kind of "frozen" conservatory music, shed of any its more ecstatic elements. At the Academy of Shashmaqam in Dushanbe, musicians are now trying to rediscover the vitality of the music and more authentic, older performance styles. The ethnomusicologist Theodore Levin, author of A Hundred Thousand Fools of God, the definitive introduction to Central Asian music, was moved to tears by a performance we witnessed there. One of the striking things about this music is how surprisingly accessible it is to Western ears, compared to, say, Indian or Chinese music.

Fairouz Nishanova, a director of the Aga Khan Trust, organised this trip. Nishanova's mother is the princess of a local principality and her father was a top Soviet politician; her connections proved invaluable, particularly when the Kygyrz military police tried to arrest me because I didn't have a visa to enter this small, mountainous country. We flew back to Kyrgyzstan to stay in a sanatorium once favoured by Communist Party bigwigs on the shores of the vast lake of Issyk-Kul. Perhaps the most impressive artistic achievement of Central Asia is the Manas epic, which recounts the exploits of the hero Manas as he battles foes and reunites the Kyrgyz clans. The epic remains popular today – I saw a plastic cola bottle with a picture of Britney Spears dressed in traditional Manas warrior queen gear.

Soviet scholars transcribed this oral epic, which has more than 500,000 lines of verse (by comparison, the Indian Mahabharata comprises 200,000 lines, the Iliad around 13,000). But when we meet the self-styled shaman Rysbek Jumabaev, he is dismissive of those who have learnt the work this way – he "received the Manas in a series of seven dreams". We heard him perform parts of the Manas in the stunning setting of the Kochkor plateau, considered a sacred site from before the time of Genghis Khan. As thunder rolled in the distance, Jumabaev contacted the spirits and then began an extraordinary performance, entering a trance-like state as he sang.

Since my trip, the Aga Khan Music Initiative has widened its horizons (including to West Africa) and it will be possible to to see a truly dazzling array of musicians this Wednesday at the Royal Albert Hall, just up the road from the Ismaili Centre. The concert is to mark the Diamond Jubilee of the Aga Khan’s leadership of the Ismailis.

Since my trip, the Aga Khan Music Initiative has widened its horizons (including to West Africa) and it will be possible to to see a truly dazzling array of musicians this Wednesday at the Royal Albert Hall, just up the road from the Ismaili Centre. The concert is to mark the Diamond Jubilee of the Aga Khan’s leadership of the Ismailis.

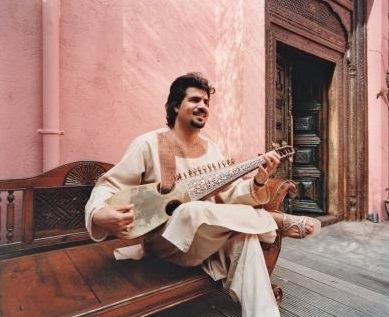

Among the stars are Homayoun Sakhi, an innovative performer of the rubab from Afghanistan; Wu Man, virtuoso on the pipa, a four-stringed lute that has been part of Chinese culture for 2,000 years; Sirojiddin Juraev, from northern Tajikstan; Basel Rajoub, saxophonist and composer-improviser from Syria; Saler Nader, virtuoso tabla player; Feras Charestan, a highly accomplished and innovative player of the qanun, a Middle Eastern zither; Andrea Piccioni, a master percussionist; and Abbos Kosimov, from a famous musical family in Uzbekistan. Probably the best known artists to Western audiences are Bassekou Kouyaté from Mali and the ever-adventurous Kronos Quartet, ageing enfant terribles of the classical world who have recorded with some of the best known Central Asian and West African artists.

At the least the concert and the ongoing work of the Music Initiative ensure that the music of this little-known region is preserved and developed for future generations, and that the wider world has a welcome chance to hear it.

- Jubilee at the Royal Albert Hall, 8pm Wednesday 20 June

As part of the celebrations for his Jubilee, the Aga Khan will be visiting the UK this month and will inaugurate the Aga Khan Centre in London’s Knowledge Quarter, Kings Cross

Add comment