It was a month before Christmas and I was watching venerable folkies the Battlefield Band at Edinburgh’s Queen’s Hall. Halfway through their set they played “Robber Barons”, a new song about the nefarious medieval practice of German feudal lords charging exorbitant tolls on traffic travelling on the Rhine; as the verses mounted, it moved – seamlessly, like all good folk songs – to expose the habits of the unscrupulous bankers of the early 21st century.

The message was clear: times may change, but we are still at the mercy of a different kind of robber baron, lining his own castle with silver while his subjects’ houses are up for repossession.

It wasn’t a particularly sophisticated point but it was, I thought, a resonant one. The Scottish capital, after all, remains both the physical and spiritual home of RBS, Public Enemy No 1 in the British leg of the credit crunch saga. On the outskirts of the city – situated near the airport, as though its thousands of inhabitants were ever ready to make a quick getaway, like Central American dictators of old - is the RBS village, a massive self-contained site which now looks like a gaudy monument to gross incompetence, and probably worse. It was finished just as the financial pillars began to crumble. A year or so ago, the entire banking structure was teetering on the edge of collapse, with RBS as Ground Zero.

Post credit-crunch, there’s certainly been those who would cleave to Basil Fawlty’s 'Don’t Mention The War' dictum

Yet in the Queen’s Hall as “Robber Barons” was played there was no great sense of release, no celebratory roar of anger or defiance. Instead, men in good suits and shiny brogues shuffled uncomfortably in their seats; young people smiled indulgently but also seemed to shrug. There was a lone cheer, but everyone else seemed a little miffed. The feeling was unmistakable: "Oh, we were having such a nice night. Why did you have to go and mention that?"

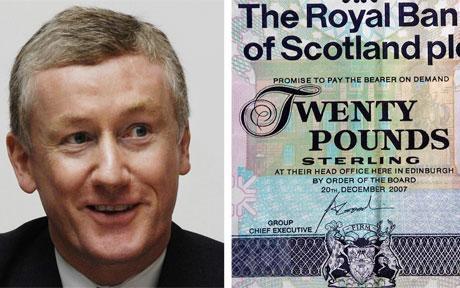

A week or so later I was at the same venue to see Lau and a similar moment occurred. The band played Les Rice’s 1950 anti-capitalist anthem “Banks Of Marble” and dedicated it to Fred Goodwin, the publicly reviled RBS chief executive who lives – or lived; he’s probably sold up and gone somewhere hot with large security gates – less than a mile from this venue. Again, a feeling of inertia rather than energy filled the room. Too close to home? Too soon? Too late? More likely, who cares? Old news. Let’s move on.

Partly these reactions are down to the time of year, which tends to drape a forgiving seasonal sheen over the most unforgivable of events, but mostly it’s about Edinburgh itself. If you’re looking for a very public demonstration of opprobrium against social injustice, the home of Scotland’s most powerful and established financial institutions might just be the last place you would come. Edinburgh isn’t an up-and-down kind of city; it doesn’t wear its heartaches and victories as ostentatiously as Glasgow. Instead, it tends towards a quiet stoicism and a tacit belief in preserving the status quo. Post credit-crunch, there’s certainly been those who would cleave to Basil Fawlty’s "Don’t Mention The War" dictum, who want nothing more than to keep quiet until the dust has cleared and the old order is once again restored.

They seem to be getting their way. The following days and weeks brought more shows, more distractions. Deer Tick played Sneaky Pete’s, a scuffed institution deep in the bowels of Cowgate. A grizzled bunch of unreconstructed Rhode Island rockers peddling classic US roots manoeuvres, their music has strong echoes of Steve Earle, only shorn of any righteous agenda; “Straight Into A Storm” sounds like Lynyrd Skynyrd playing Chuck Berry. They are good, but more crucially for those watching, they are uncomplicated. This music is about the politics of the heart rather than the pocket. Beer and beards loom large. This lot wouldn’t know Fred Goodwin from Fred Flintstone, and right now we don’t care.

A few days later I caught Deerhoof (yes, there has been a cervid bent to my recent outings: a man’s gotta doe what a man’s gotta doe) in the Bongo Club. The San Franciscans are more adventurous but no less oblivious to the bailiff banging at the gate, offering up a heavy, hazy wave of sound, often instrumental. They managed to be both ominous and twee, veering from lowering to skittish as lead singer Satomi Matsuzaki invented dance moves on the spot and took the drums for an encore of, of all things, Canned Heat’s “Going Up The Country”. It was fun, but hardly “There’s A Riot Goin’ On”.

Them Crooked Vultures, playing the cavernous Corn Exchange, are clearly too rich and cool to say much beyond “Are you having a good time?” and “Let’s get hot and sticky.” Wisely, there was no attempt to preach prudence among the flying plastic pint glasses, flickering camera-phones and beery bellows. By now, I was convinced beyond reasonable doubt that no one in Edinburgh on A Big Night Out (or even a little one) really wanted to be reminded of the catastrophes that have been partly orchestrated on their own doorstep and which are still, presumably, eating away at their wallets – either that or these are sins for which they feel partly responsible.

In any case, it appears to be having little material affect on the city’s ability to socialise. Perhaps Edinburgh’s infamous dearth of decent live music venues is making things seem more vibrant than they actually are, but the mood music is easy enough to read. Clearly, punters are still paying hefty sums for tickets and are still intent on enjoying themselves. They still drink as though today was their last, and blithely talk their way through gigs as though the appearance of a band playing music is somehow an unwelcome surprise. The capital’s pubs – for decades the beneficiaries of liberal licensing laws - are still open late and long and have no shortage of custom. Even in the freezing small hours pavements are lined with drinkers, clubbers and gig-goers nipping out for a quick smoke.

On Sunday night I went to the first of Phil Cunningham’s pair of seasonal shows, a much-loved fixture on the Christmas calendar. It was packed to the rafters with a cross-section of local society, from primary school children to OAPs, families to lone wolves, old folkies to new media types. As guests like Eddi Reader joined the fray, a few Robert Burns songs were aired, bringing the remembrance of an old revolutionary spirit if not any real heat. Protest has become just another act of nostalgia.

It struck me as I looked around not just this show but all the others I’ve attended over the past month that the democratic nature of most audiences – from those watching the defiantly marginal noodlings of Deerhoof to the ones enjoying the big league powerhouse that is Them Crooked Vultures - has dissolved boundaries of class, age and culture, meaning that these days gigs rarely provide a focal point for mass consensus. On one thing, however, it seems people are starting to agree. We don’t want to hear any more about the credit crunch. Especially at Christmas. And especially in Edinburgh.

{youtube width="400" height="300"}TX5RbEXjdPI{/youtube}

Add comment