Cinema Paradiso is having a third outing 25 years on. A commercial flop in 1988, Giuseppe Tornatore’s homage to the big screen as an escape route into other worlds excited love on a global scale only after it was re-released as winner of the best foreign film Oscar the following year. After so many films from New York's Italian diaspora had glamourised the mob, here was a bitter-sweet picture postcard from Sicily that had nothing to do with the Cosa Nostra (or very little: one local don does get popped off, but blink and you miss it).

Tornatore’s specialist subject is nostalgia - Italian lives fragmented by internal migration, and the necessity of growing away from the world of one’s childhood. It’s a fruitful line of enquiry for a country where campanilismo – loyalty to the chimes of the nearest belltower – still governs hearts. But the reason why, almost alone among his films, Cinema Paradiso travelled is down to one thing above all: to play his younger self, Tornatore found a young actor who could embody all our youthful dreams – a longing for adventure and an innocent veneration for the silver screen.

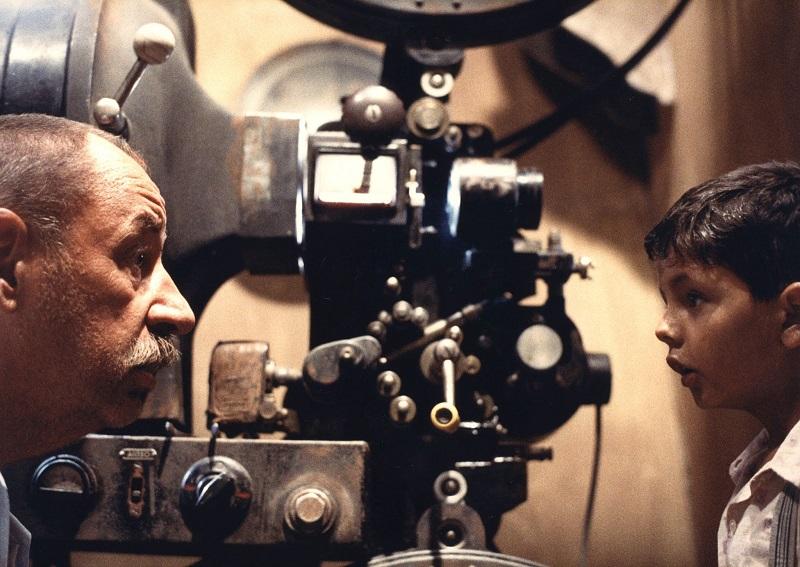

Salvatore Cascio (pictured right) plays Totò, a boy so in love with cinema that he pesters Alfredo, Philippe Noiret’s curmudgeonly projectionist in Giancaldo’s ropey old fleapit, to let him hang around and help. Totò’s father hasn’t come back from the Eastern front, so the cinema in the village square offers a refuse from home where he is battered by a lonely grieving mother. The addiction to cinemascopic escape is shared by the whole village. Cinema has replaced religion as the people’s opiate. But this being Sicily in the 1940s, the Church in the person of the tut-tutting priest still has the power to censor the naughty bits.

Salvatore Cascio (pictured right) plays Totò, a boy so in love with cinema that he pesters Alfredo, Philippe Noiret’s curmudgeonly projectionist in Giancaldo’s ropey old fleapit, to let him hang around and help. Totò’s father hasn’t come back from the Eastern front, so the cinema in the village square offers a refuse from home where he is battered by a lonely grieving mother. The addiction to cinemascopic escape is shared by the whole village. Cinema has replaced religion as the people’s opiate. But this being Sicily in the 1940s, the Church in the person of the tut-tutting priest still has the power to censor the naughty bits.

If there were such a thing as an Oscar for best boy, Cascio would have run away with it that year. His bug eyes and impish Cupid’s bow somehow fill the screen, and his scenes with Noiret (who, as in Il Postino, was dubbed into Italian) are wonderful examples of parry-and-thrust between innocence and experience. The wrench that happens halfway through the film, when little Totò grows up in a bog-standard Italian teen mooning like a milksop after a pretty blonde (pictured above left, Marco Leonardi and Agnese Nano), still causes the heart to sink ever so. This was doubtless Tornatore’s intention, but the film succumbs to a kind of blood-sugar low which finds you cheering the now blinded Alfredo on as he urges Totò to run away from Sicily and never come back. It’s only in the beautiful valediction that our hearts go back out to the film. Totò, now a celebrated film director (Jacques Perrin) who has never managed to marry, returns for Alfredo’s funeral which, in a convenient double goodbye, happens to coincide with the demolition of the cinema (to make way for a carpark).

If there were such a thing as an Oscar for best boy, Cascio would have run away with it that year. His bug eyes and impish Cupid’s bow somehow fill the screen, and his scenes with Noiret (who, as in Il Postino, was dubbed into Italian) are wonderful examples of parry-and-thrust between innocence and experience. The wrench that happens halfway through the film, when little Totò grows up in a bog-standard Italian teen mooning like a milksop after a pretty blonde (pictured above left, Marco Leonardi and Agnese Nano), still causes the heart to sink ever so. This was doubtless Tornatore’s intention, but the film succumbs to a kind of blood-sugar low which finds you cheering the now blinded Alfredo on as he urges Totò to run away from Sicily and never come back. It’s only in the beautiful valediction that our hearts go back out to the film. Totò, now a celebrated film director (Jacques Perrin) who has never managed to marry, returns for Alfredo’s funeral which, in a convenient double goodbye, happens to coincide with the demolition of the cinema (to make way for a carpark).

The other pleasure of the film is in a kind of innocent narcissism. Tornatore turns his camera on the audience as they thrill and enchant and, in the case of a front row of boys watching Bardot in And God Created Woman, masturbate. For better or worse, that's all of us up there in the mirror. The big question for anyone going back for a second look is whether the glucose levels, augmented by Ennio Morricone's score, are now intolerable. It depends on the individual but for this viewer it still pulls the right levers – above all in the wonderful final montage of screen kisses and bared breasts, spliced together as an exquisite billet-doux from yesteryear (see clip overleaf).

The other pleasure of the film is in a kind of innocent narcissism. Tornatore turns his camera on the audience as they thrill and enchant and, in the case of a front row of boys watching Bardot in And God Created Woman, masturbate. For better or worse, that's all of us up there in the mirror. The big question for anyone going back for a second look is whether the glucose levels, augmented by Ennio Morricone's score, are now intolerable. It depends on the individual but for this viewer it still pulls the right levers – above all in the wonderful final montage of screen kisses and bared breasts, spliced together as an exquisite billet-doux from yesteryear (see clip overleaf).

Perhaps there is an extra patina of meaning to Cinema Paradiso a quarter of a century down the line. It was originally a film about Italy’s relationship with its past as embodied by the benighted south. Now it seems to ask questions about its future. In the shape of the little Totò, Italy is the enchanting manipulative eternal child to whom it is impossible to say no however gruffly the rest of Europe may insist that it grow up and stop living in a fantasy. Italy is a repository of all our sentimental dreams, and perhaps we need it to remain the same.

Overleaf: watch the final montage from Cinema Paradiso

Add comment