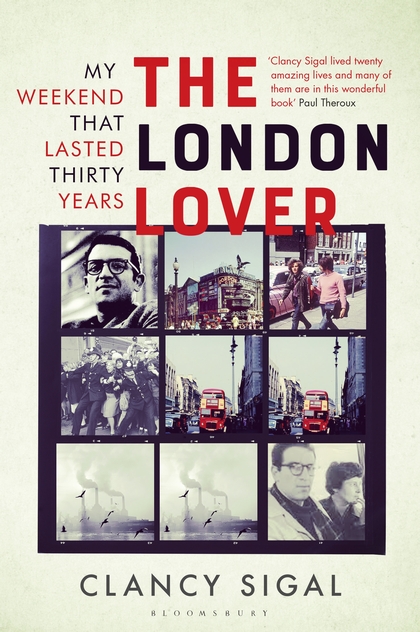

To readers of newspapers and magazines, the name Clancy Sigal will be very familiar, probably as a film reviewer. Addicted to writing, and to his old Smith Corona #3 portable typewriter, “Hemingway’s preferred machine”, he was a version of the man who came to dinner. He arrived – inevitably, for this was the early 1950s – off the boat in Dover, intending to spend a weekend exploring before returning to the US. He stayed 30 years.

“Kicked out of Paris by the French police for having a cancelled US passport and no visa” – years later, he would discover the FBI had branded him SUBVERSIVE – he jostles a teenager to distract the attention of the Immigration Officer and is soon heading up the A28 aboard a Victoria-bound bus. He has $40 in his pocket and his meagre possessions fit into a GI duffel bag, tagged Sgt C Sigal, 36929935. He is proud to be a Yankee “living rough in the Smoke”, following in the dusty footsteps of Benjamin Franklin, Henry James, Mark Twain, Hart Crane and Jack London.

George Plimpton ranked Sigal alongside Jack Kerouac and Joseph Heller, their shared genre the American picaresque. His earliest days in London are spent keeping warm on tube trains and buses, and there is certainly a Magic Bus/Merry Prankster feel about The London Lover: My Weekend That Lasted Thirty Years.

He gets lucky early on: Jean, a “clippie” on the No 88, takes a shine to him. She is “my first Englishwoman” who keeps condoms in her bedside drawer and likes a cup of tea (“three sugar lumps”) before getting down to business. She stares at what she calls (in Cockney rhyming slang) his “Mars and Venus”. Sigal apologises for its modest size and wonders to himself: “What happened to my plan to join the revolution in Poland and Hungary?”

Jean would marry her route supervisor and Sigal is soon bedded by (or is bedding – the power seems to shift) a young and divorced Doris Lessing. Indeed, readers of The Golden Notebook will know Clancy as Saul Green. They meet when he’s directed to her Warwick Road address by Stanley Harrison, editor of the Daily Worker, who says she has a room to rent. Sigal is immediately smitten by her “High cheekbones, astigmatic green eyes, Pendleton blouse”. For an American, the conditions are basic, and cold. But the sex is good and continues, on and off, for a number of years – despite the novel.

Jean would marry her route supervisor and Sigal is soon bedded by (or is bedding – the power seems to shift) a young and divorced Doris Lessing. Indeed, readers of The Golden Notebook will know Clancy as Saul Green. They meet when he’s directed to her Warwick Road address by Stanley Harrison, editor of the Daily Worker, who says she has a room to rent. Sigal is immediately smitten by her “High cheekbones, astigmatic green eyes, Pendleton blouse”. For an American, the conditions are basic, and cold. But the sex is good and continues, on and off, for a number of years – despite the novel.

The sash windows of Lessing’s “split-level maisonette” (an edit, along with Aldermaston being relocated to Hertfordshire, which should have been spotted) provide an escape route from immigration officers while Sigal explores London, and far beyond, joining CND marches and other left-leaning activities, and hanging out with gangs. Visitors include “the four Johns” – Osborne, Amis, Braine and Wain – plus occasionally Christopher Logue and John Berger. Lessing is jealous when he runs into Iris Murdoch. Listening to skiffle at a coffee bar, he tries to chat up Princess Margaret.

It’s a report of a North London gang fight that gets Clancy in to the Observer, “with its stately masthead and patrician literary journalists”. His “shadowy existence” is known and when Scotland Yard shows up, “just like in a spy movie”, it is editor David Astor who protests. The following day, the Home Office grants him permission to remain. (He’s long been availing himself of the NHS, however.)

It is Astor who suggests he go into analysis – he’s already happily paying out for sessions for many of his journalists. But analysis doesn’t work for Sigal, who has much more success with R D Laing, tripping on then-legal LSD fresh from the Swiss lab, sometimes with a Beatle or two. With the shrink he sets up A Radical Place for Healing, in Kingsley Hall, a former Baptist chapel in East London. “Incurable schizophrenics” answer Laing’s call, along with innumerable celebrities, including John Lennon.

By this time Sigal has moved from Lessing’s home to more centrally located abodes, where sex is on offer from various neighbours. Meantime he’s chronicling the life of Yorkshire coalminers for the Observer, work which leads to an invitation from Fred Warburg – George Orwell’s publisher, he proudly notes - for a book. The result is the novel Weekend in Dinlock. Then it’s back to the States, for his “American rebirth”, where he chronicles the black struggle in Georgia, meets “Miss Sara Mayfeld, a white lady of the Old Confederacy” who’d grown up with Zelda Fitzgerald, checks out Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters, and hears early testimony from disoriented Vietnam vets.

He returns to “a new and foreign London” to pick up where he left off, sort-of, and where he remains until 1984 (where the book ends) when the Observer despatches him to LA to report on the Olympics. There he re-meets and marries Janice Tidwell, forming with her a screenwriting team. He died in June 2017, failing health and vision forcing him to dictate much of his memoir.

Along the way, Sigal rubbed shoulders, Zelig-like, with innumerable history makers – some of them players, some of them walk-ons. He was, you feel, a natural-born journalist with a sharp ear, keen eye and an insatiable curiosity. His book is a long strange trip – and well worth the fare.

- The London Lover: My Weekend That Lasted Thirty Years by Clancy Segal (Bloomsbury, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment