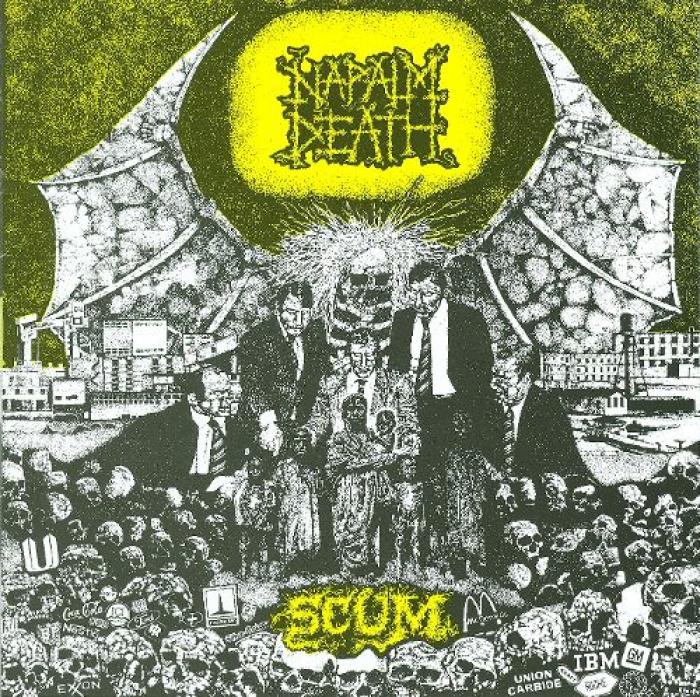

Nicholas Bullen is an artist and composer, based in Birmingham. He works across disciplines and media, including sound, installation, film, performance and text. In 1981, Bullen founded the Grindcore legends Napalm Death with Miles Ratledge. He will perform a new solo piece Universal Detention Centre at this year’s Supersonic Festival to mark the 30th anniversary of their seminal album, Scum, a disc which includes “You Suffer”, the world’s shortest song according to the Guinness Book of Records.

GUY ODDY: Scum was not only a seminal album for Napalm Death but also for the grindcore movement. What are your abiding memories of that scene from a distance of 30 years?

NICHOLAS BULLEN: I think we were at a crossroads for two sizeable sub-cultures of the time: on one hand “punk”, on the other “heavy metal”, both of which still had a lot of influence. I think what set Napalm Death apart though, was that we fused the different genres together rather than aping a particular sub-genre within them.

At the time, in England, hardcore thrash was a form that came from elsewhere and was a very minority interest. Even among many heavy metallers, it wasn’t even really seen as music at all. You know, “There’s no tunes. You can’t sing along to that.” Many of those bands would also ape American bands, so you’d have bandanas and check shirts and Converse sneakers and talk about things being “rad” and “gnarly”. We didn’t do that. We fused our particular interests and took tiny elements from different groups and different movements.

I think that in itself was fresh. We also did it with a dedication which I think set us apart from a lot of the bands in Britain at the time. The speed element was also of interest to people. Although, initially it was a very negative thing for those people that would shout abuse at us or leave the room. But that wasn’t really an issue for me at all.

Scum was a very political album, with song titles like “Multinational Corporations” and “Control”. Does it sadden you that musicians seem less confident or even interested in putting the world to rights these days?

Well, the thing is that you had the Miners’ Strike and the Battle of the Beanfield with the Travelling Community. Nelson Mandela was let out of jail. The Berlin Wall came down and then CND just disappeared in a puff of smoke. There was an attitude of “Well, it’s all right now”, and you noticed the CND sign diminishing in its usage.

I also think that the trouble with politics is that it tends towards the extreme and a lot of people are alienated by that. You think of how many people were vegetarians in the early ‘80s and part of that was the extremism of the viewpoint. That moral line that people had to obey and, if they weren’t good enough, then they were criticised and who wants to put themselves into that position ultimately?

It’s funny but the Right are the same. The internecine fighting among the Right is fascinating. But the thing is that I can see what people get out of extremism in politics, and the trouble is I am an extremist! I can be nicely Manichean – black and white!

But of course, decadence always trumps moralism. Always. If you think about the end of the ‘80s: raves, the credit card boom, living off loads of money and not having to worry. I think you then get the fall-out from that for a long time. So, you’ve got at least two generations who have been relatively non-political. I wouldn’t say apolitical but not “political”. But now you’ve got “Stormzy says Vote Corbyn”. But I don’t think that will necessarily translate because it’s an easy badge to wear and then you’re on to the next thing. It doesn’t involve any real engagement. Also, what else does Stormzy represent? Consumer capitalism? Macho sexism? It’s all in the lyrics. But then I’m looking from the outside and ruminating and I like everyone who’s shouty and noisy. I don’t discriminate. I find it all interesting.

John Peel was an early champion of Napalm Death and the Grindcore scene. Did you ever have much to do with the man?

John Peel was an early champion of Napalm Death and the Grindcore scene. Did you ever have much to do with the man?

Not really. When we were doing sessions, because they’d be at the weekends or the middle of the week, he’d be busy. But he would be seen at concerts, particularly around Ipswich. Extreme Noise Terror were from Ipswich and they’d bring a lot of other bands there.

I think his influence is more that almost everybody from that generation listened to his programme and had been opened up to lots of different kinds of music through it. It sat within a much wider continuum, back to the Blues, ‘20s dance bands, and Reggae was always there. So, it was very diverse and yet at the same time, perhaps the only place you could hear certain kinds of music. Swans certainly didn’t get played anywhere else. So, I don’t think you can underestimate his appeal and influence. But I think like everyone, he was busy.

You parted ways with Napalm Death a long time ago but they’re still plugging away and put out the excellent Apex Predator - Easy Meat album a couple of years ago. Are you still in touch with the band?

When I was in Napalm Death, I’d reached the end point of exploring that approach. I felt it was starting to limit the possibilities for me but, you know, I get absolutely fine with them. I sometimes see Lee Dorian who used to do the vocals and played on the B-side of Scum. I have talked to them before now about collaborating but time and logistics haven’t made it possible. It’s hard for me though because I tend be quite mercurial and to focus on my interests. There may be things that spark an interest but I look elsewhere for my extremities in sound.

I believe that you’ve undertaken a special commission for this year’s Supersonic Festival. What can you tell me about it?

Universal Detention Centre will be a one-off, just for this festival. It could be characterised as harsh electronics, in that it will have an electronic sound and use my voice as a further instrument – as I like to use it as a primary source of material. So, in terms of the scope of the sound, it’ll tend to be non-narrative, not necessarily linear and not focused on traditional structures. In that I mean, not in terms of song. There are rhythmic elements. Pulses. But they’re usually to add a bedrock to other developments in the electronic sound across the field.

The reason I wanted to do a harsh, electronics performance is because it’s related to Napalm Death. That was an element that I wanted to echo and also because of the subject matter. In terms of the material, all the sounds apart from the sound of my voice are from the first side of Scum and a cassette of the first Napalm Death rehearsal. Every bit of electronic sound is from those two elements, which bookends my period with the group. Consequently, it includes for me the continuum that moves through that time period and then into the future.

I also wanted to limit access to the material, which is something that I do with all of my compositions. I like to restrict because then it makes it more creative. Trying to find ways to take part of the material and build something new from it.

The purpose of it is ultimately political, to get back to Napalm Death and also links to me. I was particularly focusing on the forces used across the world for detaining those people who don’t fit into the wider programme, whether they are refugees or punks in Indonesia, and that seems to be a microcosm of the wider political world itself. I wanted to explore something that isn’t necessarily commented upon, to open it out. The title Universal Detention Centre takes the idea and opens it out across the globe. I use my own texts for my voice and I’m also using some other political texts from the past which I’ve melded together to create a range of reference points that form into a whole.

I’m looking forward to doing this performance but I think that it’ll be the last one that I do for a while. I don’t want to reduce the meaning of something to its fiscal qualities. I don’t want it just to be a commodity. I mean it would be easy to just make commodities, perhaps. But with this performance at the Supersonic Festival, I wanted to do something of myself. I could have got a Grindcore band together and played a set but that’s not want I wanted to do. The possibilities can remain open with what I have planned, which is the interesting thing really. It means you can express yourself in wider ways.

Your fellow Midlander noise merchant (and former collaborator in Napalm Death and Final) Justin Broadrick is also playing the Supersonic Festival (with Kevin Martin of The Bug). Do you have any plans to meet up with him, and could you see yourself working with him again at some point?

I’ll see him on the day he’s playing. In terms of collaboration, I probably don’t think so. But that’s not to say it would never happen. But I probably don’t think so, simply because we do have a slightly different field of interest and, on a personal level, I think I need to explore the areas I’m interested in and focus on that. And that takes enough time without thinking I really need to go to speak to other people about working with them.

You’ve worked with and formed a considerable number of outfits over the years (including Napalm Death, Final, Scorn, Germ, Umbilical Limbo, Black Galaxy, Migrant and Alienist) as well as creating sound installations and films: has there been one project that sticks out as being the most artistically satisfying?

Probably working on my own material under my name, Nicholas Bullen (pictured below by Kevin Thomas). Largely because there’re endless possibilities, there’s endless scope and it’s also freed from the need to make it easily accessible. It doesn’t rely on any financial return, which means that creatively it can be the purest expression I can find and gives me the widest scope to explore. It’s also the hardest area for me to work in, which makes it interesting in itself.

The recordings of my stuff have been on all kinds of things but I don’t really pay much attention once it’s done. I had a reappraisal of many things that I was doing many years ago now, and decided that it would work better for me to earn a living elsewhere, and that meant that everything that I did creatively was freed from any of that restriction. I do find it hard now though, as people ask me to do records or releases quite frequently and I have to say “no”.

I’ve got hundreds of compositions that I‘ve got stored at home that I’m not satisfied with. But I also feel that I don’t want to cost anybody any money, and so it was a deliberate thing to make it not an issue for me.

For my next couple of performances, I’m doing some new pieces based around “breath”. Three pieces which use one element of breath in the widest sense of “air”. I’ve got a piece made from a single trombone note. I’ve got a piece that’s from the voice and a piece from the radiators in my house. Than I’ve got another performance in Norway which is going to be just about my voice. I like to keep trying other things. I understand that they may be of limited appeal though, and I don’t particularly have a problem with that.

You started performing at a young age (Bullen formed Napalm Death with Miles Ratledge at the age of 13). Why did you choose music as a way to express yourself creatively?

I really don’t know. Music came to me in a sudden way when I was 10 years old. Before that I hadn’t really had an interest in music per se. I’d been a cultural magpie and picked at small elements. But when I discovered punk, something within me that I didn’t know, needed answering immediately and I responded to it very physically. So, I think it was only natural that I’d then go on to begin expressing myself through music at some point.

Miles and I had written songs and recorded them since 1979 in our bedrooms. Very rudimentary set-up of begged and borrowed equipment that wasn’t suited to the task, and we’d already been playing together making duo recording, where we’d do overdubbing on the tapes. Recording onto one tape and then playing over it and recording that as well. Very rudimentary form of multitracking. So, it seemed only natural, when we were a little bit older, that we would formalise a group with other people.

I was never focused on visual art. I had no ability to understand that there was a possibility to extend writing further than fanzines – possibly because I was so young. Music seemed like an immediate way to express yourself – which is the key.

In terms of other projects you’ve been involved in over the years, I was reading that you started a record label called Monium but information about it is hard to find. What happened with that?

In terms of other projects you’ve been involved in over the years, I was reading that you started a record label called Monium but information about it is hard to find. What happened with that?

Yes. It was short-lived. Its anonymous nature was, in part, deliberate. I was very excited by the possibility of the home-produced CD. Thinking in terms of tapes and how important they were for me. Cassette recordings were a really amazing way of accessing stuff. So, I produced a lot of homemade CDs of people’s music that would then be sold at live events rather than be stocked in shops.

The idea was that once they were gone, they were gone and then we’d go on to something else. It was based purely around the content rather than any desire to recoup any money that was expected, or to have any kind of longevity as a going concern. I viewed them very much like fanzines, in a sense that they had a certain amount of ephemerality built-in and they just came and went.

Miles and I would regularly write off for cassettes from all over the world and from a wide range of creativity. It was a fantastic process for opening up avenues. I first heard primitive tape looping through that, through a cassette called The Electronic Sylvia Plath which cut recordings of her voice and combined them with electronics. I think it came out of Essex. Very unusual for me at the time as a 12-year-old to be opened up to that possibility, which I’d heard in Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, but this was a fuller aesthetic. Cassettes always played that important part because they were accessible and because they were cheap.

All the early Napalm Death cassettes were recorded in homes, then duplicated in homes and then given out to people with their representative cover and lyric sheet. It was very important, that accessibility, and they bypassed the traditional structures, with the exception of the mail service.

You’ve been based in the West Midlands all your life. How do you think that the music and arts scene there has developed over that time?

In a strange way, I don’t think it’s changed at all. If you just take Birmingham for example, it’s always had a really vibrant music scene, from the R’n’B going back to the ‘60s through the post-punk era of Au Pairs, Duran Duran, Kevin Rowlands, who went on to do Dexy’s Midnight Runners and many others. But then it’s always had quite a vibrant clubbing culture. So, I don’t think it’s changed so much as it’s continued to explore and revitalise itself. I think it’s always been rather separate in that there isn’t a lot of cross-pollination between the different scenes. But I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing.

Also with the arts scene, again it’s been very vibrant when you think back to the ‘70s and you had Birmingham Arts Lab and the Ikon Gallery. There’s always been a wide range of art from traditional visual art through to conceptual art, and there is some degree of cross-over now between the arts scene and the music scene, particularly among the younger curators. I’m thinking particularly of Vivid and Centrale. They’ve been pulling together different strands and combining perhaps conceptualised performance and sound. I think that is a development that has been going on for a long time and, hopefully, will continue.

I think one thing I like about this city is there isn’t necessarily a need to look to anywhere else as there’s such a wide range of possibilities that you can see or hear, from amazing art to music, without leaving the city. But there perhaps needs to be a bigger public profile for some parts of the cultural milieu – simply because it would open it out to a wider group of people. I mean, I really try to promote BEAST (Birmingham Electro-Acoustic Sound Theatre) at the University because they’re composers who’re operating at a global level in terms of their dedication and the quality of the events they produce. I’m always trying to promote that to people.

Add comment