Time was when a Boulez concert with the LSO would have been directed by the man himself, but that is no longer possible. In Peter Eötvös they have the next best thing, a conductor who has known the man and his music for decades, whose listening ear is scarcely less acute and whose most recent appearance wth the LSO, in Lachenmann and Brahms with Maurizio Pollini, made quite miraculous music from intensive rehearsal. It was evident that similar care had gone into the preparation of orchestral rites by Stravinsky and Boulez, preceded by the Livre pour cordes which the French composer fashioned in 1968 from a suppressed string quartet.

If the opening entries were more cautious in their impression than their actual sound – see the Rituel below – the strings of the LSO burrowed purposefully into this (literally) muted refraction of the string quartet tradition, like late Beethoven filtered through the half-light of Debussy’s Jeux. Encouraged by Eötvös, they spun a delicate web of call and response no less effective in its way than the sumptuous, showpiece treatment that the Vienna Philharmonic used to give it with the composer in charge.

The offbeat chords of the final 'Danse sacrale' were phrased in medieval-style ligaturesThe Rite of Spring that followed was loud without ever becoming deafening, quiet without whispering, by and large steadily paced. So what made it out of the ordinary? The quality of listening. The orchestra played it last just three months ago, under Sir Simon Rattle, but I wonder what kind of preparation that had offered. Without taking the orchestra’s collective virtuosity for granted, Eötvös seemed to start from scratch. Flutes and piccolos fluttered and swooped through the close of the introduction with more open intonation than usual – not out of tune so much as in tune with the octatonic scale from which Stravinsky drew the Rite’s musical materials.

Even at the points of highest volume and complexity in Part One, the multiple conflicting metres – warring tribes – were counterpoised in audible and distinct arrangement: the Rite as chamber music, not concerto for orchestra. Colouristic touches such as the sighing shudders evoked by Rattle and others at the start of Part 2 build up a picture of the Rite as a single albeit multifarious event. These were shunned in favour of a less unified, more unpredictable encounter between conflicting personalities. The offbeat chords of the final "Danse sacrale" were phrased in medieval-style ligatures, gradually drawn together and superimposed on one another with a brutality that looked neither right nor left but did its work without feeling or remorse.

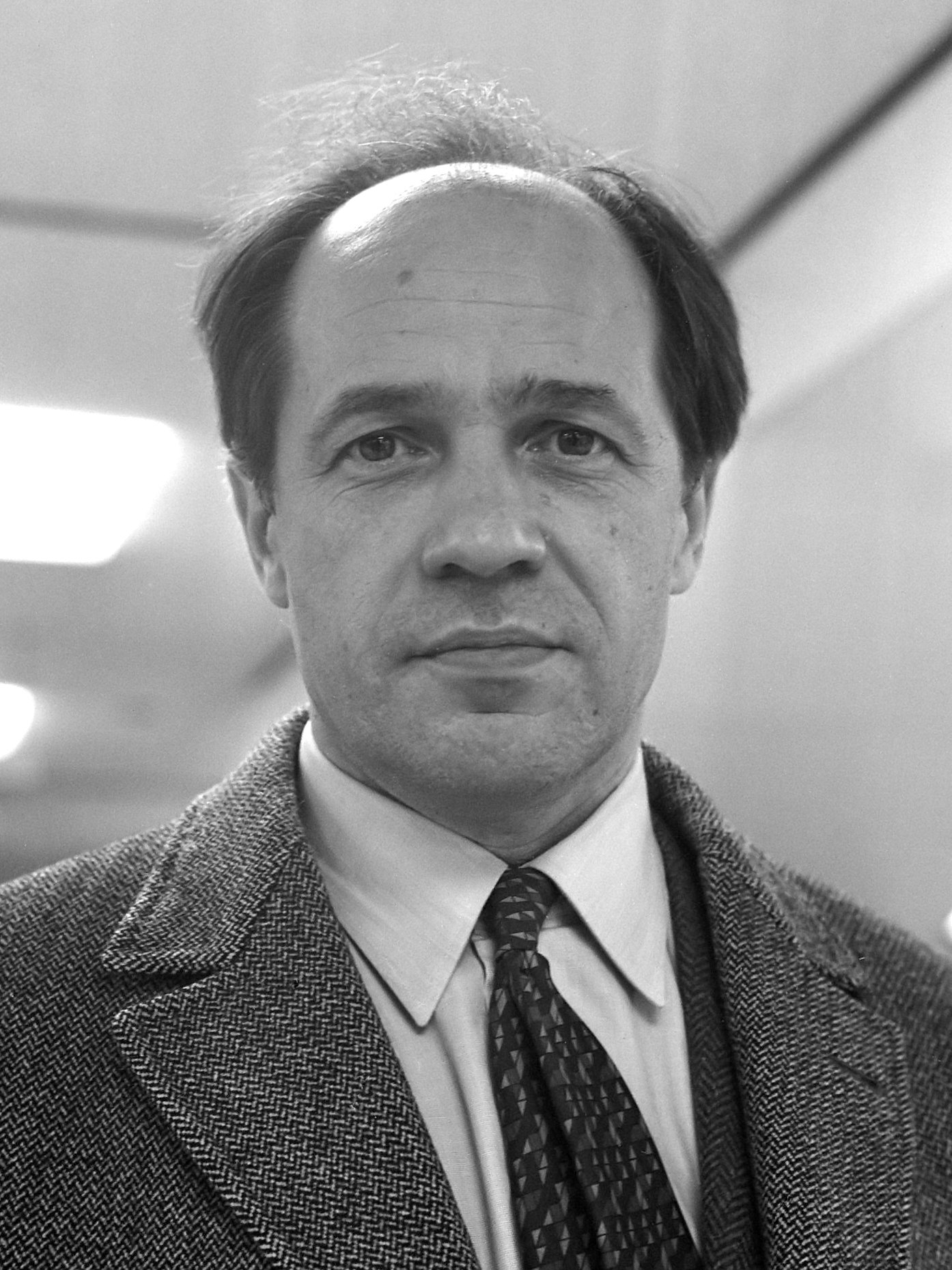

It takes a special piece to shunt the Rite into the first half of a concert, but Rituel is that piece. Boulez (pictured right in 1968) wrote it after the early death of his friend and colleague Bruno Maderna in 1973, and the grief within it is raw and angry. Something of the Italian composer/conductor’s anarchic spirit lives on in the scoring, which is for eight separated groups of instrumentalists. Each has a percussionist measuring out its own beat, and during the works’ first half they appear one by one like groups of mourners converging on a space. Not a square: that would be too regular, for Rituel is a funeral anti-march, rebelling against lockstep conformity, preserving the quality of individual response to tragedy. The form of the piece resists interpretative shaping by a conductor even as it demands an alert central figure of coordination and organisation: again, this may be considered a politically motivated move in the postwar era to call not only for new kinds of music but new musicians, unhierarchically prepared to work together for a common cause.

It takes a special piece to shunt the Rite into the first half of a concert, but Rituel is that piece. Boulez (pictured right in 1968) wrote it after the early death of his friend and colleague Bruno Maderna in 1973, and the grief within it is raw and angry. Something of the Italian composer/conductor’s anarchic spirit lives on in the scoring, which is for eight separated groups of instrumentalists. Each has a percussionist measuring out its own beat, and during the works’ first half they appear one by one like groups of mourners converging on a space. Not a square: that would be too regular, for Rituel is a funeral anti-march, rebelling against lockstep conformity, preserving the quality of individual response to tragedy. The form of the piece resists interpretative shaping by a conductor even as it demands an alert central figure of coordination and organisation: again, this may be considered a politically motivated move in the postwar era to call not only for new kinds of music but new musicians, unhierarchically prepared to work together for a common cause.

A great deal of irregularity is implied by the score, and still more is left to the judgment of the conductor, so it was not possible to say exactly how much uneven rhythm was by chance or design. Eötvös gave clear enough cues and chose a steady basic tempo, slower than Boulez himself. Even so, for the first half of the piece, as the ensembles entered one by one, the feeling of insecurity was there and never quite disappeared. The groups played to their own beat when they had to, and came together when they should. However, most of the groups were tentative in attack, most prominently the six strings, and not all the percussionists were as sure of their part as Sam Walton and Neil Percy.

Given the nonchalant ease with which the LSO met some unusual and exacting requirements in Stravinsky, their lack of confidence was dismaying. Here was a top-ranked orchestra playing a 20th-century classic, rehearsed and directed by a conductor experienced in both idiom and work. What it needed was either greater basic familiarity or another rehearsal session and a couple more performances, as it would have had on tour or on the Continent. Classic? A step too far, you say? Let us take the BBC Proms as a barometer of classical programming. All the major works of Boulez have been heard there, as might be expected given that he was principal conductor of the BBCSO for five years, but with five performances, Rituel is his most-performed work (as well as his most frequently recorded, even more than the orchestral Notations), and the composer conducted none of them; 31 years ago, it was led by Eötvös, and he conducted it with the London Sinfonietta in 2008, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. He last appeared at the Proms 12 years ago. They need him back.

Add comment