At around the same time that Oliver Postgate, that singular genius of children’s television, was knocking up new worlds in his garden shed in Kent, so, in a garden shed in Wiltshire another remarkable maverick, Professor James Lovelock, was assembling a new world of his own. Postgate’s was a moon inhabited by Clangers, while Lovelock’s was a re-imagining of Earth as “Gaia” - and what is perhaps unexpected is that it is children’s entertainer Postgate who comes across as the more melancholy of the two men. Lovelock, by contrast, seems remarkably chipper for a doomsayer who predicts the imminent mass extinction of humanity.

Postgate had only a benignly neglectful BBC to contend with; Lovelock was up against a scientific establishment that he clearly despairs of. “Nearly all scientists these days are slaves”, was just one of many tasty statements made during the course of the second part of Paul Bernays' Beautiful Minds, an intelligent and uncondescending three-part series that reminds you just how far BBC Two’s Horizon has fallen since the decision was taken to make it more “popular”.

Lovelock came across as eminently sane, lucid, humorous and reasoned – his calm in the face of extinction so at odds with the more strident noises of the ecology movement, and all the more chilling for it. But Bernays’ film wasn’t primarily just another platform for the eco-prophet of doom to expound views that were here compared to Copernicus displacing the Earth from the centre of the universe, or Darwin displacing God from the centre of creation. It was more a look at the conditions that allowed his originality to flourish in the first place.

There were biographical elements to Lovelock’s freedom of thought: the nature-loving father who made a present to the young lad of a box of old wires, switches and bulbs, and told him to get on with it; a boyhood spent freely roaming the vaults of Brixton's public library; and a job at the National Institute for Medical Research in wartime London. Apparently the great scientific minds of this establishment, usually firmly closed to callow underlings, opened up as V-1 flying bombs scraped past the building – a passing-on of wisdom inspired by the proximity of their own mortality, reckoned Lovelock.

By contrast, the aridity of his science lessons at grammar school nearly put Lovelock off the subject for life – while inculcating a vital spirit of resistance that would become sorely tested once he had proposed his theory of our planet as a self-regulating organism (the name Gaia – the Greek goddess of the Earth – was suggested by his friend and neighbour, William Golding, it transpires). To Lovelock’s surprise, it was religious people, including the Church of England, who first embraced his grand idea, followed (to Lovelock’s displeasure) by the New Age counter-culture. I first came across Gaia in Troy Kennedy Martin’s 1985 BBC drama Edge of Darkness, as the guiding philosophy of Joanne Whalley’s murdered anti-nuclear protester, which is retrospectively ironic given Lovelock’s recent conversion to nuclear energy.

The first scientific critic of Gaia to go into print was an unfortunately-named (given mankind’s sluggish response to climate change) biologist, W Ford Doolittle, followed, considerably more destructively, by Professor Richard Dawkins, who frightened off other scientists so that it became impossible for Lovelock to publish in reputable journals (“Dawkins hated Gaia as much as he hated God”, chuckled his victim). I was interested to see whether Dawkins, seen here in archive form, had recanted at all in the intervening years, and was now willing to accept that Lovelock may have been just a little bit right after all, but there was no new input from the evangelical atheist.

Lovelock’s strength - and his weakness from the point of view of the rigidly micro-specialised scientific community - is that he is a polymath. Actually more of a natural physicist and mathematician than a chemist, a mild form of dyslexia meant that he couldn’t tell his right from his left, and had difficulty writing equations. He is variously described as “thinking out of the box”, “thinking around corners” and thinking “at an angle”, and Lovelock ascribes much of his success to keeping out of academia. Instead, as mentioned above, he works from his glorified garden shed, building his own instruments, including the “electron capture detector” with which he first realised that the atmosphere was saturated with fluorocarbons emitted from spray-cans and leaked by fridges.

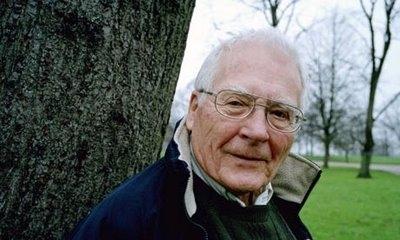

He may have missed out on a Nobel Prize (Mario Molina and Sherwood Roland claimed that in 1995 for their subsequent work on the depletion of the ozone layer), but you get the feeling he doesn’t care. As he says, he’s “totally blue sky... it’s not done for the money, it’s just done for curiosity and interest.” This may even be the secret to his longevity. And if he remains calm and cheery, it’s not because, at the age of 90 (but looking a good 15 years younger), he knows he’ll be dead sooner rather than later. He might, he says, live to be 100 and, by his calculations, in 10 years' time his terrible vision of the future may have started to arrive.

Add comment