Male dancers are a puzzle to British audiences, where they are an uncomplicated, taken-for-granted treasure in Latin or Slav countries. I point this out gratuitously, as it's a point that wasn't touched upon by Melvyn Bragg's film about three iconic men of ballet, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov and Carlos Acosta.

But this was not a historical survey of attitudes to male dancers and how Oliver Cromwell messed with British heads - that interesting possibility remains unrealised on TV. This was about the act of fleeing slavery to find freedom, from constricted motherland to liberated Western art world, Nureyev and Baryshnikov both being Soviet Union defectors, Acosta having left Cuba. The familiar escape stories were retold, flavoured by some insightful comments by the ballerina Tamara Rojo, who asked if the public didn't in fact love this "outsider" status to use it to romanticise their view of them.

Extremes of emotion have been replaced by extremes of motion

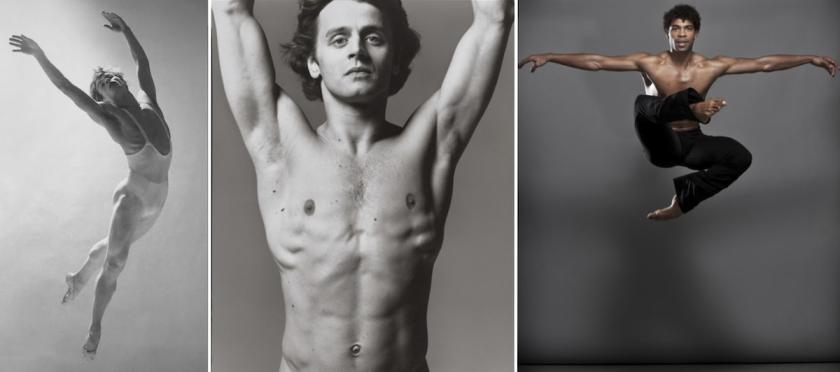

She's right - yet there was enough performance film here to excite. Nureyev, always on the edge, daring and feral, a high-wire-over-Niagara-Falls act; Baryshnikov, supremely well-contained in his natural brilliance; Acosta, the most courteous of them, the most careful, the most self-tamed. It's easy to forget that dancers are rarely filmed, and indeed hardly ever filmed at the point the public would most want them to be.

Bragg’s interviews with all three, dating back to 1991 in Nureyev's case, discovered little in common between them except for their news-making emigrations, and we were left no wiser about what their past training particularly contributed to their lustre nor what they passed on to other male dancers.

But the programme did unwittingly expose how the British view of male dancers now has subtly altered, along with the dismantling of barriers and mystique between men and women in our society. Rojo said that "when a male dancer captures the public it's usually because he's outrageous, and so it should be. His dance is usually more abandoned and wild." It was evidently true of Nureyev in the clips and interviews - a magnetic, restive character seen in his last years, naked on his Caribbean island, gilding his self-image as an innately isolated soul.

But outrageous isn't so easy now. To talk of a “male star” is not so simple nor even, maybe, as welcome. Today's Royal Ballet principal Edward Watson performs the more dramatic roles arrestingly (pictured right in Mayerling, by Charlotte MacMillan) but told Bragg he finds fulfilment dancing the abstract gymnastic ensembles of the choreographer Wayne McGregor, exercising his remarkable physique, rather than tearing out his emotions and psychoses. Extremes of emotion have been replaced by extremes of motion, you might say.

But outrageous isn't so easy now. To talk of a “male star” is not so simple nor even, maybe, as welcome. Today's Royal Ballet principal Edward Watson performs the more dramatic roles arrestingly (pictured right in Mayerling, by Charlotte MacMillan) but told Bragg he finds fulfilment dancing the abstract gymnastic ensembles of the choreographer Wayne McGregor, exercising his remarkable physique, rather than tearing out his emotions and psychoses. Extremes of emotion have been replaced by extremes of motion, you might say.

That leap - from the fervent male drama of personal dislocation that MacMillan felt Nureyev had uncorked in the Sixties and Seventies (a time of large changes in male perception, sexuality-wise) to the cool, nerveless athletic feats expected of today's male dancers - was not explored, a large question begged.

Their stories and motivations were compared: Nureyev an angry poor boy seeking a place of personal validation, Baryshnikov (more intellectual) seeking to join modern cultural conversation, Acosta (less solipsistic) fuelled by regret for what his native Cuba was not doing, and storing up stuff to take home again for his countrymen's sakes. His career, he said, was "a compensation pursuit".

Too little was revealed of the peculiar demands and complexity of male ballet steps and technique, the tricky balance between showstopping solo athleticism and partnering of ballerinas, and what extra talent it was that drove a stellar artist past merely executing them precisely to making every single step sing out with some instinctive meaning. Baryshnikov, sporting an unflattering little moustache, analysed the pre-defection Nureyev as "lacking basic skills, a very sloppy dancer" who had "streamlined" himself in the West. Today's male dancers, he said, are technically far superior to Nureyev and himself when they were young. Acosta pointed out, however, that when he watched video of Nureyev and Baryshnikov, he saw inspiring creatures who not only performed astonishing jumps but "cultivated the imagination of the mind. That's crucial."

For added proof, there was the choice footage of Lynn Seymour, the original bad girl of MacMillan's Mayerling, technique simply not visible as she slid and twiddled herself around David Wall like a plasticine model to be fitted to his fantasy, unbelievably erotic in effect. You asked no questions about ballet as an art form with her.

But technical matters, crucial as they are, were not Bragg's area so much as perception and image, and he threw Michael Clark's punk, ambiguous creations of the 1980s into the mix briefly to bring the male dancer up to date. Clark, in fact, was a key evolution in “the male dancer” and he could fruitfully have been examined further. So too could the astounding Akram Khan (pictured left with Sylvie Guillem, by Tristram Kenton), who fuses contemporary dance conventions to the powerfully masculine depictive traditions and mystique of Kathak.

But technical matters, crucial as they are, were not Bragg's area so much as perception and image, and he threw Michael Clark's punk, ambiguous creations of the 1980s into the mix briefly to bring the male dancer up to date. Clark, in fact, was a key evolution in “the male dancer” and he could fruitfully have been examined further. So too could the astounding Akram Khan (pictured left with Sylvie Guillem, by Tristram Kenton), who fuses contemporary dance conventions to the powerfully masculine depictive traditions and mystique of Kathak.

Yet was it because their backgrounds are formed from England and its cosmopolitan cultural stewpot, and not about romantic escapees from foreign badlands, that they were not made part of this story?

Add comment