When asked about her most famous short story, "The Lottery", Shirley Jackson said, “I hate it. I’ve lived with that thing 15 years. Nobody will ever let me forget it.” Sixty-eight years later, it’s seared into the American psyche and has been a set text for decades. It was published in the New Yorker in 1948 and generated more mail – about 300 letters, mainly horrified - than any work of fiction the magazine had published.

It’s still chilling, this calmly told story of everyday villagers who have a yearly ritual: that of stoning one of the members of their close-knit community to death. Some of the letter-writers believed it to be true. Its success put Jackson firmly in the public eye, which unnerved her – partly because now the neighbours in North Bennington, Vermont (her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, was a lecturer at Bennington College) knew who she was. Rumours of black magic swirled, not surprisingly, as she called herself a “practicing amateur witch”.

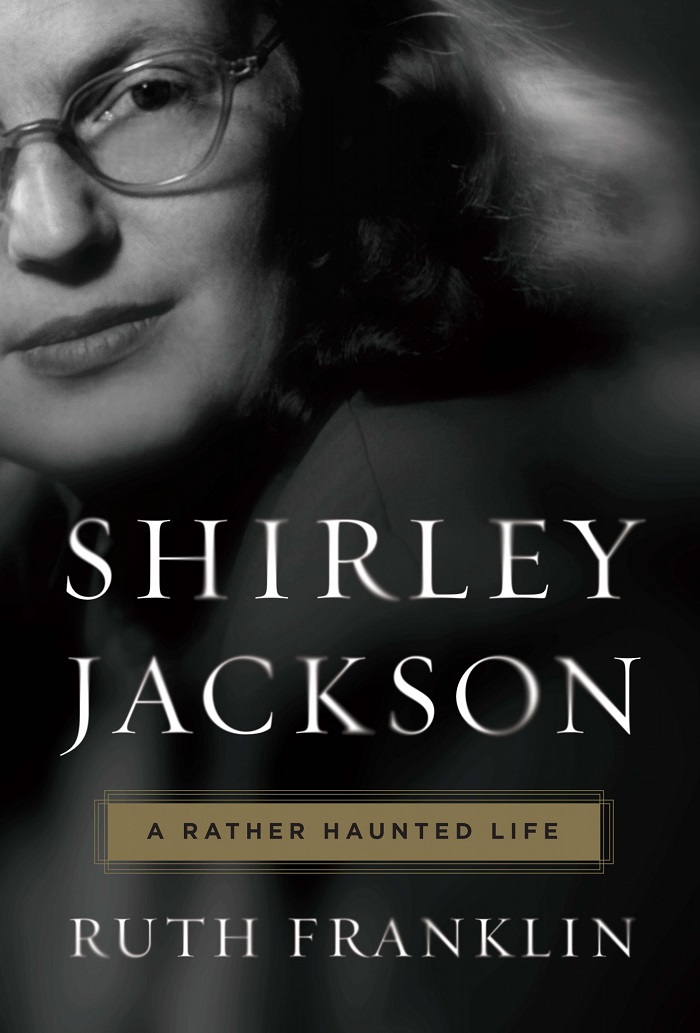

In her biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, Ruth Franklin plays down the broomstick tag and skilfully unpicks the threads of Jackson’s life and work. She gives vivid insights into the world of literary agents and editors in 1940s and '50s New York, as well as exploring Jackson’s hard-partying social circle – Hyman was a New Yorker writer as well as an academic and critic, and their friends included Ralph Ellison, Howard Nemerov and Dylan Thomas (she had a brief, drunken fling with him and dedicated one of her more mysterious short stories, "A Visit", to him. It’s included in Dark Tales, a newly published collection).

In her biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, Ruth Franklin plays down the broomstick tag and skilfully unpicks the threads of Jackson’s life and work. She gives vivid insights into the world of literary agents and editors in 1940s and '50s New York, as well as exploring Jackson’s hard-partying social circle – Hyman was a New Yorker writer as well as an academic and critic, and their friends included Ralph Ellison, Howard Nemerov and Dylan Thomas (she had a brief, drunken fling with him and dedicated one of her more mysterious short stories, "A Visit", to him. It’s included in Dark Tales, a newly published collection).

"The Lottery", although she didn’t like being defined by it, echoes a theme that is present in much of Jackson’s fiction (to help pay the bills, she also wrote jolly pieces for magazines about domestic life with Hyman, their four children and many cats): that of scapegoating and of cruelty towards the outsider, often in apparently idyllic settings – "Summer People", also in Dark Stories, is another wonderful example.

She’s also very skilled in the subtle exposure of racism and prejudice. In the story "A Fine Old Firm", in the collection The Lottery and Other Stories, Mrs Friedman pays a visit to the WASP-y Mrs Concord – their sons are both in the army – and you have to read it twice to glean the anti-Semitism within. And "Flower Garden", a story of a woman being shunned in an initially friendly Vermont community where unspoken racism forms a poisonous backdrop, is a slowly unfolding marvel. But often the more insidious poison is in the protagonist’s mind - a self-destructive, inescapable force.

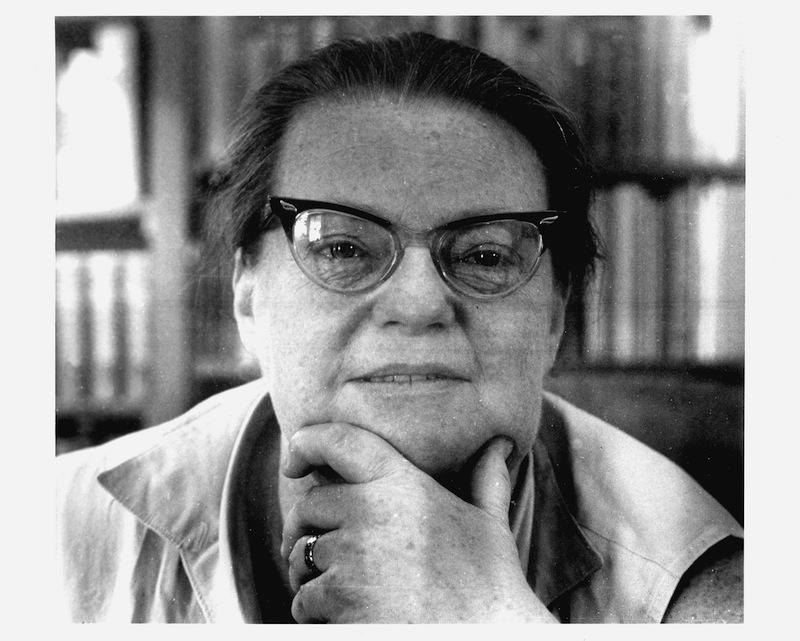

Franklin is keen to home in on the limitations imposed on Jackson as a pre-Feminine Mystique woman of the Fifties (she was born in 1916). A clerk asks her to state her occupation when she arrives at a hospital to give birth to her third child; she tells him to put writer. “I’ll just put down housewife,” he replies. But in spite of many stress factors, including a nightmarishly critical mother and an unfaithful and unhelpful husband – her earnings were much higher than his, which sometimes annoyed him - she was very good at using the chaos of her messy household as copy for her bestselling books about her children, Life among the Savages and Raising Demons, as well as writing four collections of stories and six novels. The last one, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, published in 1962 and acclaimed as her masterpiece (it sold 30,000 copies), is a brilliantly strange, claustrophobic tale of two sisters who barricade themselves in against the torments of the outside world.

Franklin is keen to home in on the limitations imposed on Jackson as a pre-Feminine Mystique woman of the Fifties (she was born in 1916). A clerk asks her to state her occupation when she arrives at a hospital to give birth to her third child; she tells him to put writer. “I’ll just put down housewife,” he replies. But in spite of many stress factors, including a nightmarishly critical mother and an unfaithful and unhelpful husband – her earnings were much higher than his, which sometimes annoyed him - she was very good at using the chaos of her messy household as copy for her bestselling books about her children, Life among the Savages and Raising Demons, as well as writing four collections of stories and six novels. The last one, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, published in 1962 and acclaimed as her masterpiece (it sold 30,000 copies), is a brilliantly strange, claustrophobic tale of two sisters who barricade themselves in against the torments of the outside world.

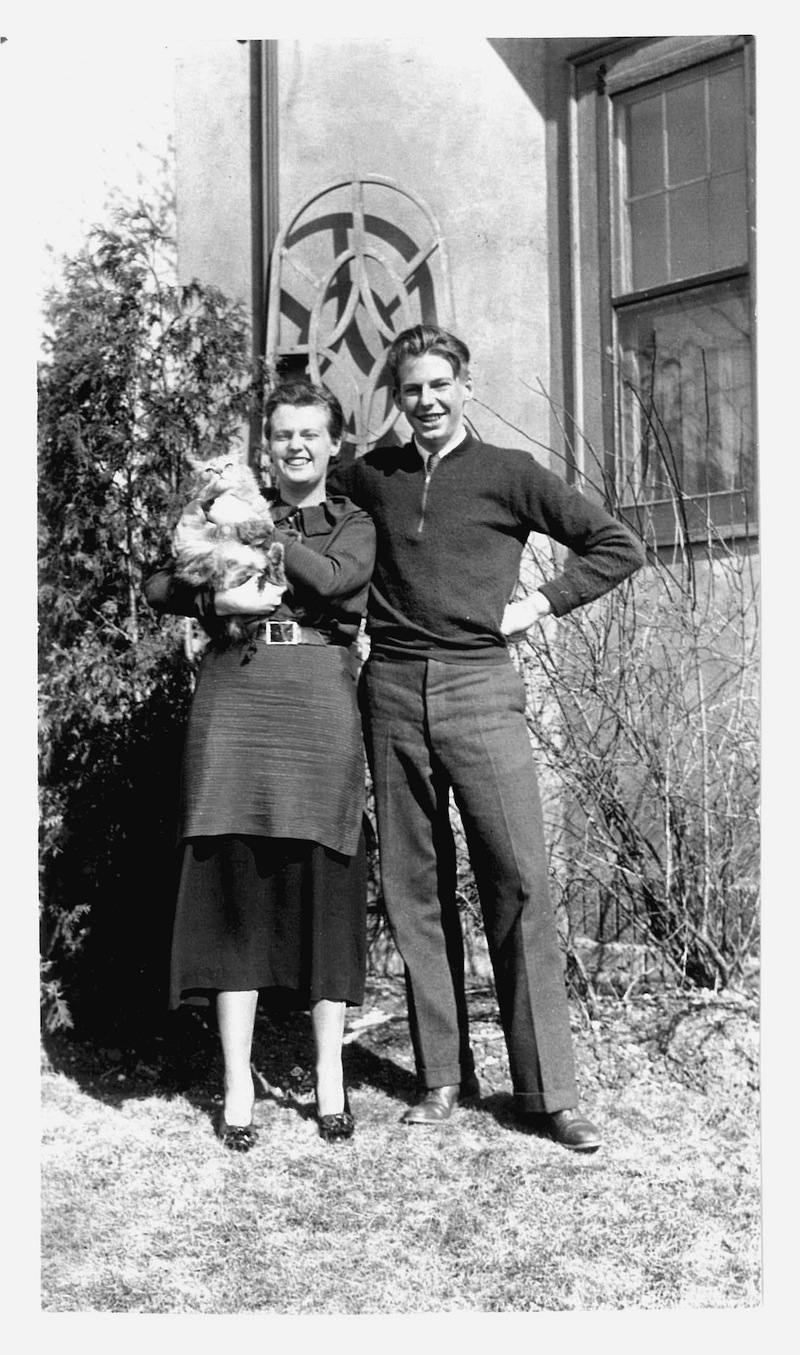

Jackson (pictured above with her brother, Barry Jackson, c. 1935) came down with crippling agoraphobia, anxiety and writer’s block not long after its publication. The crisis may have been sparked, Franklin says, by mood swings caused by the amphetamines and tranquilisers she was prescribed, as well as by one of her mother’s typically unsupportive letters in which instead of congratulating Jackson on her wonderful reviews, she just criticised her appearance in a photo in Time. Jackson was also obsessed with Stanley’s affair with one of their close friends, a former student of his who even moved in with them for a while.

Finally the block lifted and she wrote three new stories, all with the theme of homes that have been corrupted: the unnerving "Home" and "The Bus" are both in Dark Tales. Towards the end of her life – she died, seriously overweight, as she had been for years, when only 48 - she was planning to leave Stanley and wrote in her diaries of the wonderful possibility of being “separate, alone” and of a “glorious world of the future”. She never found it, but Franklin succeeds in bringing Jackson’s demons and angels into sharp, satisfying focus in the present.

- Dark Tales by Shirley Jackson is published by Penguin Classics

- Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin is published by Liveright

- Laurence Jackson Hyman's memories of his mother written exclusively for theartsdesk

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment