William Klein + Daido Moriyama, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

William Klein + Daido Moriyama, Tate Modern

William Klein + Daido Moriyama, Tate Modern

New York and Tokyo seen in grainy black and white through the lenses of an American and a Japanese

William Klein’s exhibition opens with Broadway by Light (1958), a celluloid elegy to advertising made in the days before neon. Myriad bulbs flash the names of brands like Coca Cola, Camel, Budweiser and Pepsi across New York’s night sky.

Dubbed the first pop art film, it has a celebratory mood that is in stark contrast to the black and white photographs of the city for which Klein is justly famous. His wide-angle shots are crowded with people taking part in marches, political rallies, religious meetings and funerals or simply hanging out in Chinatown, Harlem, Brooklyn or Central Park. In response to his camera, adults grin, leer, menace or posture, while gun-toting kids pull threatening faces. Klein’s love of signage is apparent in shots of hoardings and the lettering on street signs, shop fronts, vans, clothing, garbage and graffiti.

The pictures were intended for a book envisaged “as a tabloid gone berserk, gross, grainy, over-inked, with a brutal layout, bull-horn headlines. This is what New York deserved and would get.” But his unflattering view of the city horrified American publishers, so the book had to be published in Paris, in 1956. Since recognised as one of the most iconic photo books of the postwar era, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (An Anagram of Chance Witness Reveals) had a huge impact on photographers such as Daido Moriyama, whose Tate Modern retrospective follows the rooms dedicated to Klein.

The pictures were intended for a book envisaged “as a tabloid gone berserk, gross, grainy, over-inked, with a brutal layout, bull-horn headlines. This is what New York deserved and would get.” But his unflattering view of the city horrified American publishers, so the book had to be published in Paris, in 1956. Since recognised as one of the most iconic photo books of the postwar era, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (An Anagram of Chance Witness Reveals) had a huge impact on photographers such as Daido Moriyama, whose Tate Modern retrospective follows the rooms dedicated to Klein.

Klein later turned his unflinching eye on Rome, Moscow (above right: Bikini, Moscow, 1959) and Tokyo. Understandably, these photos feel like the response of an outsider to an alien culture, but the New York pictures could also have been taken by a stranger, which suggests that Klein felt ambivalent towards the city of his birth. Born in Manhattan in 1928, he grew up in a predominantly Irish neighbourhood on the edge of Harlem, a Jewish boy who never felt he belonged. He later studied sociology, became a radio operator during World War II and won his first camera in a poker game, then left New York for Paris.

In Paris he studied with Fernand Léger who advised him “to get out of the galleries” and “think about the street”. Klein’s fascination with signage prompted him to make paintings based on letter forms, which led to a commission to make rotating room dividers for a Milan apartment. He photographed them in action, fell in love with the blurring effect of their movement and began experimenting in the darkroom. He produced photograms (abstract patterns made with paper stencils), which he exhibited alongside the kinetic panels. The editor of American Vogue saw the work and offered him a job as a photographer so, after eight years away, Klein returned to New York and the rest, as they say, is history.

In Paris he studied with Fernand Léger who advised him “to get out of the galleries” and “think about the street”. Klein’s fascination with signage prompted him to make paintings based on letter forms, which led to a commission to make rotating room dividers for a Milan apartment. He photographed them in action, fell in love with the blurring effect of their movement and began experimenting in the darkroom. He produced photograms (abstract patterns made with paper stencils), which he exhibited alongside the kinetic panels. The editor of American Vogue saw the work and offered him a job as a photographer so, after eight years away, Klein returned to New York and the rest, as they say, is history.

In his fashion shots (pictured above left), Klein contrasted the supercool elegance of the models with the gritty realism of his street photography, often taking the models outside to mingle with the unsuspecting crowds. His film Who Are You Polly Maggoo? (1956), a satire on the fashion industry, reveals his contempt for the business that provided him with a living. Several documentaries followed – on Muhammad Ali, Little Richard and Black Panther, Eldridge Cleaver. (Clips are included in the exhibition and screenings are programmed for November and December).

Ironically more than 50 years on, the beauty of Klein’s gross, grainy and brutal photographs is apparent. In many ways ahead of his time, he should be accorded the respect given to seminal figures such as Andy Warhol; but perhaps because he left America, perhaps because he has operated outside the art world for so much of his career, he hasn’t received the same degree of adulation.

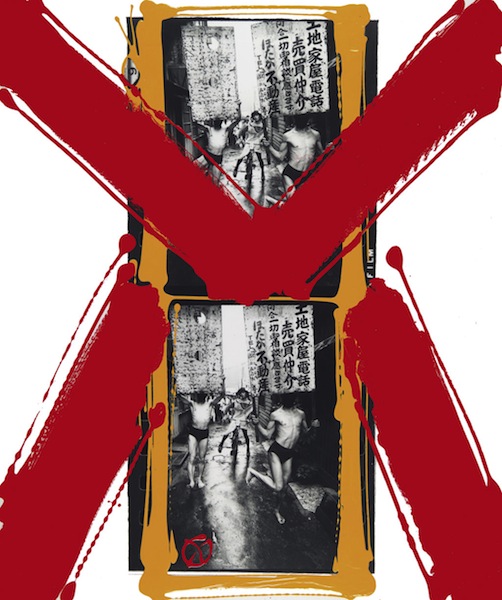

The last room feels like a bid for that kind of recognition. Enlarged sections from his contact sheets are attached to foam panels (pictured right: Dance Happening in Ginza, Tokyo, 1961). The wax crayon used to outline a chosen shot has been replaced by enamel paint freely splurged around the images to create elegantly arty panels. For the first time in his career, Klein seems to be following fashion rather than pioneering a look, trying to seduce rather than to shock his audience – understandable but sad.

The last room feels like a bid for that kind of recognition. Enlarged sections from his contact sheets are attached to foam panels (pictured right: Dance Happening in Ginza, Tokyo, 1961). The wax crayon used to outline a chosen shot has been replaced by enamel paint freely splurged around the images to create elegantly arty panels. For the first time in his career, Klein seems to be following fashion rather than pioneering a look, trying to seduce rather than to shock his audience – understandable but sad.

Stepping from here straight into the retrospective of Japanese photographer, Daido Moriyama is a bit of a jolt. In 1971, Moriyama took a photo of a stray dog glancing warily over its shoulder to assess its surroundings (pictured overleaf: Misawa, 1971). Since then he has obsessively returned to the shot, as though this image of the wolf-like loner were some kind of self-portrait. He even tilted his autobiography Memories of a Dog, as though his profession had cast him in the role of a restless wanderer never able to settle or come in from the cold.

Whether photographing in Tokyo’s crowded streets or in the isolated town of Tono in north-east Japan, Moriyama seems always to be on the outside, recording random sightings and chance encounters with strangers whose lives appear remote, alien or incomprehensible. In cities, the restlessness and sense of alienation seem endemic; commuters wait listlessly on platforms; a woman disappears down a rubbish-strewn alleyway; in the red-light district, a dancer spreads her legs; other performers take to the streets; and no one seems at ease or at home.

Whether photographing in Tokyo’s crowded streets or in the isolated town of Tono in north-east Japan, Moriyama seems always to be on the outside, recording random sightings and chance encounters with strangers whose lives appear remote, alien or incomprehensible. In cities, the restlessness and sense of alienation seem endemic; commuters wait listlessly on platforms; a woman disappears down a rubbish-strewn alleyway; in the red-light district, a dancer spreads her legs; other performers take to the streets; and no one seems at ease or at home.

After reading Jack Kerouac’s classic beat novel On The Road, Moriyama began photographing the roads leading into and out of Japanese towns. Instead of places people live in and feel comfortable with, he portrays cities primarily as destinations to be visited and left behind. The resulting book, Hunter (1972), is described as a “road map of images from all over Japan through a moving car window. Routes and roads are the hunting field for me as a photographer.”

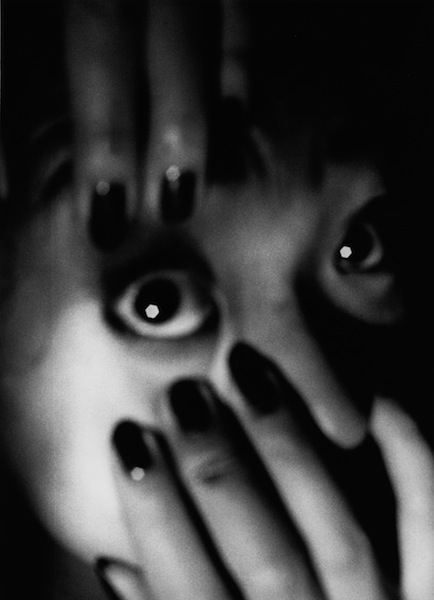

Occasionally he finds beauty – in snowflakes falling, a train speeding past, or the patterning of fishnet tights or perforated steel – but ramping up the contrast of his black and white prints, Moriyama more often portrays the world as a dangerous place engulfed in existential darkness.

Occasionally he finds beauty – in snowflakes falling, a train speeding past, or the patterning of fishnet tights or perforated steel – but ramping up the contrast of his black and white prints, Moriyama more often portrays the world as a dangerous place engulfed in existential darkness.

In all this chaos, his studio appears like a beacon of calm and stability. Recorded in a grid of polaroid shots, the room is recreated as an installation that offers a rare glimpse of clarity and colour in what can otherwise feel like a miasma – the world as seen through a dark fog.

While Klein undoubtedly influenced Moriyama’s love of grainy, out-of-focus shots taken from odd angles, to pair him with the American tells only half the story. Warhol was equally important as the inspiration behind his Accident series, which includes car crashes, shipping disasters, executions and a health scare linked to overcrowded beaches. Moriyama’s use of found images (the car crashes come from posters), his fascination with serialisation (banks of tins on supermarket shelves) and with juxtaposing unrelated images on a page were also inspired by Warhol. So pairing him with Klein is interesting, but doesn’t do him justice. Moriyama deserves to be seen as a law unto himself, rather than an acolyte of a more familiar western photographer.

- William Klein + Daido Moriyama at Tate Modern until 20 January

Watch a clip of Who Are You Polly Magoo?

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

more Visual arts

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Issy Wood, Study for No, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris review - too close for comfort?

One of Britain's most captivating young artists makes a big splash in Paris

Add comment