Treasures from Budapest: European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Treasures from Budapest: European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele, Royal Academy

Treasures from Budapest: European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele, Royal Academy

A rich goulash: an exhibition that will exhaust and delight

Treasures from Budapest – phew! It’s overwhelming. One staggers out quite cross-eyed and wobbly-kneed. There are over 200 works, for heaven’s sake. And so many Virgins: sweet-faced Italian Madonnas, austere Eastern European Madonnas, pallid German ones. There’s a tiny, exquisite yet unfinished Raphael Madonna, known as The Esterházy Madonna, since much of the collection of Old Masters shown here was amassed by Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy. Oh, and there’s the stubby-nosed, chinless Viennese one by an unknown altar-piece painter (such an arrestingly odd face; are her eyes actually going in the same direction?). She can’t compete in the beauty stakes, but you’re spoiled for choice in the line-up.

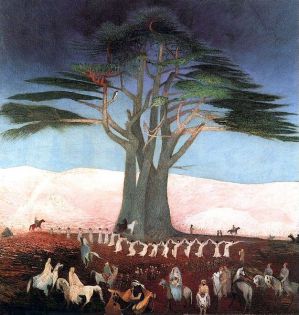

Still, cross-eyed or not (me, not the pregnant Viennese Virgin), it’s difficult to come away from the exhibition not pleased to have become acquainted with so many of Hungary’s fine-art treasures. And though we’re not overwhelmed by too many native artists, there are a few beguiling Eastern Europeans of the early 20th century to make you want to know more, such as Hungary’s own Tivadar Csontaváry Kosztka (a line of white-robed nymphs, looking like a bunch of crazy druids dancing round a tree in his Pilgrimage to the Cedars of Lebanon, 1907: pictured right); or another Hungarian Symbolist, and one of the country’s most popular artists of the 20th century, József Rippl-Rónai.

Still, cross-eyed or not (me, not the pregnant Viennese Virgin), it’s difficult to come away from the exhibition not pleased to have become acquainted with so many of Hungary’s fine-art treasures. And though we’re not overwhelmed by too many native artists, there are a few beguiling Eastern Europeans of the early 20th century to make you want to know more, such as Hungary’s own Tivadar Csontaváry Kosztka (a line of white-robed nymphs, looking like a bunch of crazy druids dancing round a tree in his Pilgrimage to the Cedars of Lebanon, 1907: pictured right); or another Hungarian Symbolist, and one of the country’s most popular artists of the 20th century, József Rippl-Rónai.

Still, the Royal Academy’s exhibition title is a bit misleading. There is just one Egon Schiele – a scurrilous 1915 watercolour of two lesbians involved in a spot of frottage, one in a kind of strange, pink frou-frou dress and who, dare I say, could pass for a gentleman in over-the-top sexy lingerie – but the last century is not particularly well represented. The Renaissance and the Baroque pretty much triumph.

Jacob Jordaens’ Fall of Man, 1630 (pictured left), for example, stops you in your tracks, though this may be because the couple look like a pair of middle-aged lushes. Jordaens was Rubens’ most talented pupil, and he depicts the amply fleshed Eve right at the point of accepting the Serpent’s offer of the apple. Surrounded by the fat of the land, the scene, nonetheless, is rather ordinary, domestic: humble farm animals gather round - a cow, a sheep, a foraging goat with its rump smack in the middle of the picture, on the same vertical line of vision as the proffered apple. It contrasts greatly with the rather exotic treatment of the same subject by Jan Brueghels, a close friend and collaborator of Rubens.

Jacob Jordaens’ Fall of Man, 1630 (pictured left), for example, stops you in your tracks, though this may be because the couple look like a pair of middle-aged lushes. Jordaens was Rubens’ most talented pupil, and he depicts the amply fleshed Eve right at the point of accepting the Serpent’s offer of the apple. Surrounded by the fat of the land, the scene, nonetheless, is rather ordinary, domestic: humble farm animals gather round - a cow, a sheep, a foraging goat with its rump smack in the middle of the picture, on the same vertical line of vision as the proffered apple. It contrasts greatly with the rather exotic treatment of the same subject by Jan Brueghels, a close friend and collaborator of Rubens.

The exhibition is crowded with big names, though there are far less celebrated painters who also cajole and dazzle. One such is Sleeping Girl (main picture). Although previously ascribed to Veronese, she is, in fact, by an unidentified painter, noted as active in Rome in the first half of the 17th century. Her head, which is dressed in jewelled flowers and feathers and pearls, rests on folded arms, one hand still clutching a lace handkerchief. A smile plays on her lips as if she is dreaming of a lover, whose scent, perhaps, she can still smell on that white kerchief.

The exhibition also presents an impressive number of drawings, and it is here that Leonardo presents himself in two dimensions, rather than in painting (there are also two equestrian sculptures). Two sketches of the heads of soldiers, produced for the Battle of Anghiari mural that no longer exists (for the Hall of the Grand Council of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence), one bordering on generic caricature, the other incomparably life-like (pictured right). The dramatic force of their expressions, which convey the unrestrained ferocity in the heat of battle, was given a specific term by Leonardo: pazzia bestialissima – bestial madness.

The exhibition also presents an impressive number of drawings, and it is here that Leonardo presents himself in two dimensions, rather than in painting (there are also two equestrian sculptures). Two sketches of the heads of soldiers, produced for the Battle of Anghiari mural that no longer exists (for the Hall of the Grand Council of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence), one bordering on generic caricature, the other incomparably life-like (pictured right). The dramatic force of their expressions, which convey the unrestrained ferocity in the heat of battle, was given a specific term by Leonardo: pazzia bestialissima – bestial madness.

Leonardo was not alive when the Florentine Republic achieved its decisive victory against the Milanese at Anghiari in 1440, but in his imagination at least, he clearly must have been to have produced these treasures.

- Treasures From Budapest: European Masterpieces from Leonardo to Schiele at the Royal Academy until 12 December

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment