theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Peter Blake | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Peter Blake

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Peter Blake

The godfather of Pop Art pays tribute to 10 artists who have inspired him

Peter Blake (b 1932) seems to have gone seamlessly from a groovy Sixties mover and shaker – he would probably dispute that but, after all, he did hang out with The Beatles – to National Treasure. His new one-man exhibition, Homage 10 x 5 – Blake’s Artists, is a tribute to 10 of the artists who have excited and interested him over the past 50 years. “These are my nod of appreciation,” he says. “A way of saying thank you to the artists I like.”

Trained at Gravesend School of Art and the Royal College of Art, Blake quickly decided to paint the subjects that had enthralled him since his teens - wrestlers, music-hall entertainers, film stars – which, combined with his trademark planes of bright colour and use of collage, paved the way for English Pop Art. In 1969 he moved to Wellow in Somerset and a year later he became a founder member of the Brotherhood of Ruralists, a group of artists who took their inspiration from nature and the Pre-Raphaelites, and exchanged painting blowsy strippers for Titania and Ophelia. (Homage to Henri Matisse, pictured above.)

Trained at Gravesend School of Art and the Royal College of Art, Blake quickly decided to paint the subjects that had enthralled him since his teens - wrestlers, music-hall entertainers, film stars – which, combined with his trademark planes of bright colour and use of collage, paved the way for English Pop Art. In 1969 he moved to Wellow in Somerset and a year later he became a founder member of the Brotherhood of Ruralists, a group of artists who took their inspiration from nature and the Pre-Raphaelites, and exchanged painting blowsy strippers for Titania and Ophelia. (Homage to Henri Matisse, pictured above.)

However, in 1979 he returned to London where he has lived ever since and his work continues to draw upon a wide range of sources from popular culture, often combined with references to other artists. Embraced by the YBAs, he was the Associate Artist at the National Gallery from 1994-96 after which he announced he was retiring. He later explained that he was retiring from all he did not like in the art world, such as “jealousy and avarice” and, indeed, he continues to work as hard as ever. Ongoing projects include a forthcoming book of alphabets, the illustrations to a new edition of Under Milk Wood (so far 10 years in the making) and a commission from the Knights Bachelor for a painting to hang in the corner of St Paul’s where Millais is buried – the artists’ equivalent of Poets’ Corner.

An inveterate collector, Blake’s vast two-storey studio could quite legitimately be described as a folk museum of the Fifties and Sixties. Birds’ nests, tiny figures of people afraid of B-movies (of which more later), Kendo Nagasaki’s mask and Tom Thumb’s calling cards are all neatly displayed alongside signed photographs of Sixties pop icons, although items come and go – several pieces have recently been sent to the Museum of Everything in Primrose Hill which Blake is co-curating with James Brett.

It is from this magpie-like hoard that Blake has created his latest exhibition, consisting of five pieces of work dedicated to each of the 10 artists he has chosen to pay tribute to, taking the artist’s style and making it his own. The artists are: Joseph Cornell, Sonia Delaunay, Mark Dion, Damien Hirst, Henri Matisse, Jack Pierson, Robert Rauschenberg, Kurt Schwitters, Saul Steinberg and H C Westermann.

HILARY WHITNEY: Did you have ambitions to be an artist from a very early age?

PETER BLAKE: Absolutely not. In fact Miss Gaspar, the headmistress of Maypole School in Dartford, which Mick Jagger attended several years later, was the only teacher to single me out because of my art until I was 14. I was five years old and I drew a picture of Miss Gasper chasing me with her cane as I tried to scramble over the school wall. Apparently she was rather taken with it and she pinned it up, although I’m not sure whether she liked it because she thought it was a good drawing or because it appealed to her sense of humour – she was a kindly woman and I’m quite sure she never caned anyone.

I wasn’t at that school for very long, however, because when I was seven, my sister Shirley and I were evacuated. It was all very fast. War was declared on the Sunday and there was an instant panic. There was only one Anderson air-raid shelter in our street in Dartford and there was also the added complication that my brother was about to be born - he was actually born 10 days later on 13 September - so my parents arranged for us to be evacuated to this village called Helions Bumpstead in Essex. It was an unofficial evacuation, arranged by someone in our street who came from there, so Shirley and I were the only children at the school who didn’t come from the village and we were considered rather freaky.

We stayed with a family called the Lofts and it was a very strange household. Mrs Lofts wasn’t unkind, she used to buy us a comic every week as a treat, but she was also very strict and very religious and we had to go to church three times on a Sunday wearing our best clothes. It was a great revelation when I came back to Dartford after the war and realised you didn’t have to wear a little grey flannel suit on a Sunday, you could wear what you liked.

We stayed with a family called the Lofts and it was a very strange household. Mrs Lofts wasn’t unkind, she used to buy us a comic every week as a treat, but she was also very strict and very religious and we had to go to church three times on a Sunday wearing our best clothes. It was a great revelation when I came back to Dartford after the war and realised you didn’t have to wear a little grey flannel suit on a Sunday, you could wear what you liked.

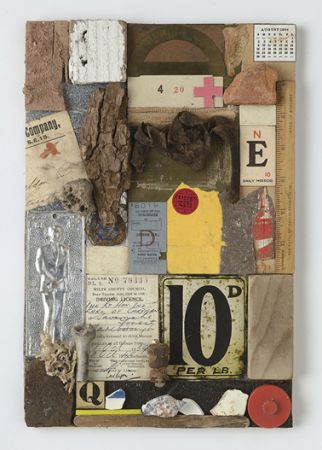

Mr Lofts had been in the Navy and by then was a batman at Greenwich Naval College. He would come back every three months with great stories of being at sea. They had a very gangly son who was about 12 and spent his whole time clutching a plate, pretending to drive a bus, and a daughter who was about the same age as me. She had a little withered hand and was slightly unstable - she once chased my sister around with a carving knife. (Homage to Kurt Schwitters, pictured above.)

There were also two lodgers: Phil, a farm labourer, who was a bachelor and had probably lived there all his life. He got up at five o’clock every morning and would fart all the way down the stairs – and they were very steep stairs. The other lodger was Mr Grace, who was most intriguing. His leg had been amputated on the battlefield during the Boer War and he had retreated from everyday life. He hardly ever came out of his room and the priest would visit him every Friday, although very occasionally you’d glimpse a very tall figure on the top of the hill with one leg and crutches.

There was no electricity, just paraffin lamps that had to be cleaned every morning and the water came from a pump in the kitchen. Mrs Lofts was quite a good cook but the food was pretty basic and the bread was always at least a day stale because she believed that freshly baked bread was bad for you. Sometimes we ate quite odd things like crow, pigeon or rabbit – country food that they could get their hands on – although Phil was sometimes able to get us extra rations from the farm, extra cheese and eggs and so on.

We were never subjected to physical cruelty but it was an unhappy time and it was far worse for Shirley because she was so much younger. We used to be given a penny for sweets but we had to earn that penny by filling buckets with the soil from molehills, which was quite distressing. On Sundays we would be sent for a long walk after the evening service, I suppose so that the family could have some time together and I would refuse to walk with Shirley simply because she was my little sister.

It was like a missing childhood and although it did affect me, it affected Shirley far more. I look back on it now a bit like National Service – something I had to get through. It was also quite pointless because there would be a period of a kind of false peace, so we’d come back to London and then it would all start again, so I was in London for all the bad stuff – the Blitz, the Battle of Britain, the doodlebugs.

For the last year of the war I was evacuated to my grandmother, who was equally weird. I didn’t pass my 11 Plus so I had to go to this really rough secondary modern where you were caned for the slightest misdemeanour. And again, it wasn’t an official evacuation, so I was the only kid there who wasn’t from Worcester – everyone thought I was from Birmingham because my accent was different. Then I came back to Dartford and spent a year at the secondary school there. That was another rough school but the headmaster was a kindly man. He arranged for me to do the exam for the technical school in Gravesend and when I went to do the exam, I was told that if I popped round the corner and did a drawing test - because the art school was part of the technical school - I might be able to go to the art school, which is what happened.

But up until that point, apart from Miss Gaspar, there had been no recognition of your artistic ability?

No, although it might have been different if I’d been at home. People have sometimes asked me if my parents were artistic and there again, I think their situation would have been different if they’d been born a generation later. My dad was always drawing little pictures for us and obviously loved drawing but he didn’t have the chance to go to art school – he was an electrician. My mother came down from Newcastle to be a nurse and then she got married and had a family, but she loved making clothes and I’m pretty convinced that if she had been born just a bit later, she’d have done a fashion course.

So what was it like at Gravesend School of Art?

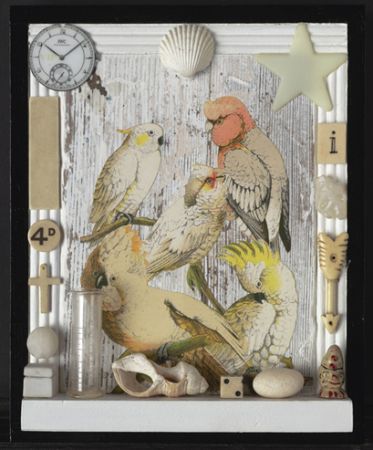

It was a very old-fashioned, nicely run art school. We were building up to the Intermediate exam – which had been in place since Queen Victoria’s reign, although we were the last year to take it - so we were taught wood-carving, stone-carving, wood-engraving, life-drawing, costume life-drawing, architecture, anatomy. It was an incredible education. For instance, the Italians were traditionally great artists’ models, so this Italian family would turn up - you’d have the husband and wife and the child - and they’d have the gypsy costumes, the Roman togas or whatever you wanted. (Homage to Joseph Cornell, pictured right.)

It was a very old-fashioned, nicely run art school. We were building up to the Intermediate exam – which had been in place since Queen Victoria’s reign, although we were the last year to take it - so we were taught wood-carving, stone-carving, wood-engraving, life-drawing, costume life-drawing, architecture, anatomy. It was an incredible education. For instance, the Italians were traditionally great artists’ models, so this Italian family would turn up - you’d have the husband and wife and the child - and they’d have the gypsy costumes, the Roman togas or whatever you wanted. (Homage to Joseph Cornell, pictured right.)

Wasn’t Quentin Crisp one of the models?

Yes, there were one or two famous gay models – Johnny Noble was another one, who worked all the London art colleges and would come down to Gravesend and Bromley as well. I certainly remember drawing Quentin during my first year at Gravesend – I would have been just 14 and still wearing grey flannel shorts and there was Quentin, who would only have been in his twenties then, an extraordinary apparition with full make-up, dyed-blue hair and blue fingernails. There’s a great story about him leaving the art school to catch the train and a lorry driver leaning out of his cab shouting, “You’re a bloody fairy!” and Quentin replying, as quick as anything, “If I was a fairy, dear, I’d wave my magic wand and turn you into a pile of shit!” It might be apocryphal but it’s a great story.

After the Intermediate exam you had to choose which course you wanted to do for your National Diploma. I wanted to do painting but the general advice was that it would be too difficult to make a living as a painter and I was advised to do the commercial art course, which I did. But one of the teachers, Peter Todd, who had taken an interest in me, thought I should apply to go to the Royal College of Art and, quite against the wishes of the other staff, helped me get my portfolio together.

I actually tried to get in as a graphic designer but Sir Robin Darwin, who was the Principal then, sometimes used to sit in with the tutors when they went through the portfolios, and he saw a painting of my sister that I’d done at home and suggested that the painting tutors should have a look at my folder – which they did and I was accepted into the painting school.

That was quite a marked change of fortune.

Yes. I wouldn’t have known much about it but I did know other people who’d gone from Gravesend to the Royal College and I was very excited. However, having been accepted into the Royal College, I had to do two years National Service, which was compulsory then. It was neither nice nor horrible – I was just killing time until I could go to art college. So I came out of the Air Force in June 1953 and went to the Royal College in the October to join these big hairy paint-bespattered painters – graphic designers were always rather smart. Suddenly I was surrounded by these very serious, proper painters – Frank Auerbach was the year above me, Leon Kossof was in my year – and there was I, a half-trained graphic designer, training to be a painter.

There was something of a sea-change at art colleges at that time, wasn’t there?

Yes, suddenly there was a Labour Government and a lot of people, like myself, who wouldn’t have been able to go to college before the war and were now able to get a grant. It was definitely a key factor in the emergence of Pop Art. I mean, my interpretation of Pop Art is that there were three key stages. It started in the States in 1953 with [Jasper] Johns and [Robert] Rausenburg and was picked up in London, by Independent Group, which was a discussion group really, consisting of people like Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton and the Smithsons [architects Alison and Peter].

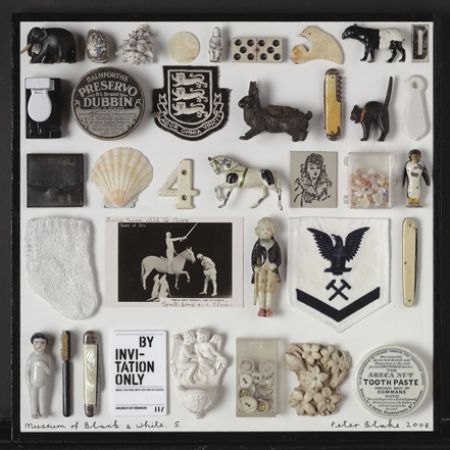

I was at the Royal College, having come out of this working-class background and, having spent my first year doing life-drawing or painting, I started thinking, what do I do now? All the studios at the Royal College were life rooms so at any time you had 10 models with a group around them and that was the basis of what you did. Beyond that there was the still-life room which had a cupboard where a trumpet and a Chianti bottle and a bottle of VAT 68 were kept, so you’d buy an apple and set up a traditional still life. But there was also something called a composition room which was a bit of a throwback to the time when you were told to paint a picture incorporating three men, a dog and an aeroplane, except that I started to paint autobiographical things, the children reading comics, that kind of biographical matter. (Homage to Mark Dion, pictured above.)

I was at the Royal College, having come out of this working-class background and, having spent my first year doing life-drawing or painting, I started thinking, what do I do now? All the studios at the Royal College were life rooms so at any time you had 10 models with a group around them and that was the basis of what you did. Beyond that there was the still-life room which had a cupboard where a trumpet and a Chianti bottle and a bottle of VAT 68 were kept, so you’d buy an apple and set up a traditional still life. But there was also something called a composition room which was a bit of a throwback to the time when you were told to paint a picture incorporating three men, a dog and an aeroplane, except that I started to paint autobiographical things, the children reading comics, that kind of biographical matter. (Homage to Mark Dion, pictured above.)

So what did your tutors make of that?

Well, things were already happening. There were the Kitchen Sink artists – Jack Smith and John Bratby and [Derrick] Greaves – who were sort of working-class social realists, and people like Frank Auerbach and Joe Tilson were around. But to answer your question, the staff at the Royal College were Johnny Minton, Carel Weight and Ruskin Spear – and Spear was already painting pictures of people in pubs, barmaids, people with handkerchiefs knotted on their heads, that kind of thing. In one way it was in the tradition of Sickert and in another it was the pre-amble to Pop Art. Spear was always slightly scornful of what I was doing – “What are you up to now, Blakey?” he used to ask – but I think he was also intrigued by these funny little pictures of boys and badges and things.

You left the Royal College in 1956 and thanks to a Levehulme scholarship you were able to travel extensively around Europe. That must have been amazing after grey old post-war England.

Well, I’d never been abroad before at all. It was a scholarship given by Leverhulme, the big soap company up in Liverpool, and until then it had been very academic, it hadn’t covered art at all. I saw the other entries and they were very much what I’d call in the academic art league, and were to do with things like studying the light on North European churches. I just said I wanted to study popular art and got £500 to travel for a year and make a report at the end of it.

I set out with a group of friends who were having a holiday in Rotterdam for the weekend and then they went home and I was completely on my own with Europe ahead of me. It was incredibly exciting. Although I was meant to be studying popular art, Colin Hayes, who was one of the tutors at the college, gave me a list of what to do and see and which towns to go to, which was pretty much the Grand Tour. So I was partly following that and at the same time, in those days most towns had a folk museum which I would visit. I also did lots of popular-culture things, like going to wrestling matches. I went to a lot of bull fights in Spain, picked up old cigarette packets and things like that. I kept the cigarette packets and then about five years ago, I found them again in a drawer and they were brilliant – one had a target on, so maybe that totally anticipated the targets I did.

I had some great experiences. I travelled with a circus for a while and then I travelled for a while with a Scottish artist called Peter McGinn in his Bedford van. We crashed outside Monaco and went to a British garage to be told that it would take a week to get hold of the necessary part. We were totally broke but the man at the garage said that the Catholic seminary would put us up. So we went and rang on the bell and interrupted this American priest, Father Tucker, who was in the process of introducing Grace Kelly to Prince Rainier. But he let us use his library floor where we slept and answered phone calls from Grace Kelly.

But let me take you round the studio and show you some of the work that will be in the Waddington exhibition. Not all of it’s here, some of it’s at the gallery being photographed for the catalogue.

We start to make our way around the vast barn-like building which, despite being crammed full of Blake's many and often quite bizarre collections, appears to be extremely well organised. One gets the impression that Blake could locate his Elvis Christmas-tree decoration or the hat Douglas Fairbanks wore as Robin Hood in a jiffy.

So this is Saul Steinberg. (Homage to Saul Steinburg, pictured right.) What I’m doing is taking drawings that he’s done and translating them into sculptures. He made sculptures himself and they were always made of plywood, so I’ve used the plywood as a hint of that but then I’ve used real objects to recreate his drawings. This is based very specifically on Double Still Life.

So this is Saul Steinberg. (Homage to Saul Steinburg, pictured right.) What I’m doing is taking drawings that he’s done and translating them into sculptures. He made sculptures himself and they were always made of plywood, so I’ve used the plywood as a hint of that but then I’ve used real objects to recreate his drawings. This is based very specifically on Double Still Life.

Then this is for Mark Dion (pictured above) who did the exploration of the foreshores of Tate Britain and Tate Modern and exhibited everything he found from Roman antiquities through to a phone card in a great big cabinet. It was literally everything they found - apart from mud or stones. This isn’t anything like that but it’s thanking him for the right to excavate stuff and exhibit it.

My tribute to H C Westermann is a series of galleons with battles going on. This one is Farmers versus Punks. I had the figures of the farmers anyway but I put one of the seven dwarfs in so that people will go, “Well, they’re not all farmers.” I got the punks from the States - you can buy packets of punks, you get four in a packet, and my daughter Liberty, who lives over there, sent me three or four packets. Look at this very angry blonde girl who’s shouting at that poor little farmer.

Originally I had some soldiers and I wondered who they could be battling with - I thought Disney characters would be quite nice and it went on from there. One of the pairings is Knights in Armour versus People Frightened by B-Movies – yes, you can also buy packets of people frightened of B-movies in America.

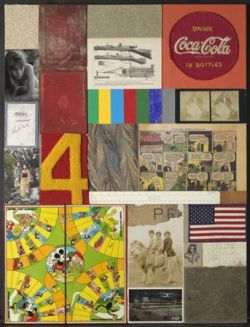

And that’s one of the Rauschenberg homages. I must explain that I attempted to paint like him but I couldn’t do it as he paints so beautifully, so they are very formalised Rauschenbergs. I used children’s board games because I had a huge collection from boot sales and I thought they were rather pretty so I made it into a kind of running theme. Oh and this [Blake is waving a stick in the air], this is nothing to do with the Waddington exhibition. It’s a stick that a fan gave Ian Dury. It’s a Rhythm Stick!

You taught Dury, didn’t you?

I did – at Walthamstow and then at the Royal College and I remember very clearly the first morning I met him. When I was a teacher I had a mad principle that I wouldn’t leave the house until nine o’clock - I didn’t want to be consumed by teaching – and as Walthamstow was a train journey and a long bus ride away, I arrived about two hours late. The headmaster said, “Your class has gone out drawing somewhere in Walthamstow, you’d better go and find them.” However, I had a hangover so I went into the nearest pub for a beer only to find Ian in there with two of the other students so that’s how we met. Obviously, I wasn’t going to moan at them - well I couldn't really, could I? - so I bought them all a drink and we were friends from that moment.

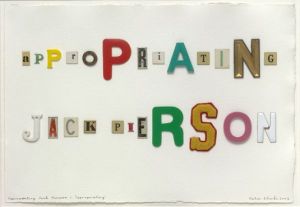

Ah, this is for Jack Pierson. The whole idea for the exhibition started with this - Appropriating Jack Pierson (pictured left). I liked Pierson’s work and wanted one for myself, so decided to make my own. He [Pierson] said he didn’t mind because he’d been influenced by my work but when he saw Appropriating Jack Pierson, he said, “That really spooks me,” so I did another collage called Spooky using ghostly lettering.

Ah, this is for Jack Pierson. The whole idea for the exhibition started with this - Appropriating Jack Pierson (pictured left). I liked Pierson’s work and wanted one for myself, so decided to make my own. He [Pierson] said he didn’t mind because he’d been influenced by my work but when he saw Appropriating Jack Pierson, he said, “That really spooks me,” so I did another collage called Spooky using ghostly lettering.

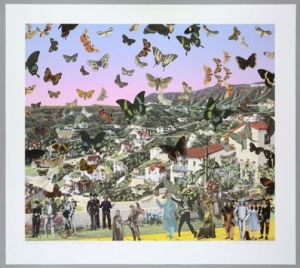

Now these are in homage to Damien Hirst and they are part of an ongoing series called The Butterfly Man. The background is an inkjet print and then all the butterflies and the crowd are collaged.

Do you have an assistant to help you?

No, I do it completely by myself. If you look, you’ll see that all the figures are cut out with scissors. I do that kind of thing at home. I have a very comfortable desk in the sitting room and I sit with my back to the television – although if the football is on, I’ll turn round to watch the goal when they play it again - and cut things out or do illustrations for Under Milk Wood. It’s how I relax.

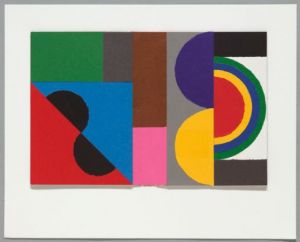

And this is for Sonia Delaunay. She was the wife of Robert Delaunay, who was the more famous of the two, but she made beautiful book jackets and some wonderful clothes. But she had a difficult life and she wasn’t as famous as she ought to have been.

OK. Now I’m sure you’re tired of talking about this, but I’m going to have to ask you about The Beatles.

[Very pleasantly, considering] I know.

I read that you said you would have rather done the cover for Pet Sounds [by The Beach Boys] than Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Is that true?

It’s true that I said it, yes. Because of the fallout, it’s true. You know the story, I’m sure – we [Blake and Jan Howarth, Blake’s first wife who co-designed the Sgt Pepper album cover] were only paid £200 and Apple behaved very badly. I’ve now given up on it but I still feel that The Beatles didn’t really appreciate the visual help they got - it was always an integrally important part [of their albums] and they’ve never really credited us for that. They certainly never have financially and never really gave us the due we should have had – and that includes Richard Hamilton who designed The White Album and Eduardo [Paolozzi] who worked for them a lot. (Homage to Damien Hirst, pictured above.)

It’s true that I said it, yes. Because of the fallout, it’s true. You know the story, I’m sure – we [Blake and Jan Howarth, Blake’s first wife who co-designed the Sgt Pepper album cover] were only paid £200 and Apple behaved very badly. I’ve now given up on it but I still feel that The Beatles didn’t really appreciate the visual help they got - it was always an integrally important part [of their albums] and they’ve never really credited us for that. They certainly never have financially and never really gave us the due we should have had – and that includes Richard Hamilton who designed The White Album and Eduardo [Paolozzi] who worked for them a lot. (Homage to Damien Hirst, pictured above.)

You met The Beatles right at the beginning of their career and by the time you worked on Sgt Pepper, they were beyond famous.

Well, The Beatles story is that I first met them at the recording of their first TV show in London. A friend of mine called Philip Harrison, who was an art director for the BBC, had been working in Liverpool and he told me there was some really good music up there. He gave me a whole list of bands, people like Gerry and the Pacemakers and The Undertakers. The Beatles were also on the list but although they didn’t get a special mention or anything, they just got bigger and bigger. Then Philip came back to London and when he was working on The Beatles’ first TV show, which came out of Twickenham, he invited me to the rehearsal. I’m not sure which show it was but Billy Fury was at the top of the bill. Philip introduced me to them at the rehearsal and then after they had recorded their song in their little grey suits with high collars they had to do some interviews. They came and sat right in front of me and they kept turning round and doing stuff like this [grins and does the thumbs up sign] and kind of informally incorporated me into the conversation.

Then, not long after that, they were playing Luton and Bob Freeman, the photographer, had done one of their covers so we went to the gig and came back to London to meet them at their hotel. We sat in the foyer with George, John and Ringo – Paul wasn’t there – and George eventually said, “I’m tired, I’m going up to bed,” and then John said, “Do you know any clubs in London? We’ve never been to any of the clubs.” I’d been taken a week before to a club called the Crazy Elephant which was the smart club to go to at the time - I wasn’t a member but I thought we’d give it a try so we all got into Joe Tilson’s jeep and set off for the Crazy Elephant. I went up to the doorman – The Beatles' latest record was playing, "Please, Please Me", I think - and I explained the situation and asked if we could come in. He asked if I was a member and I said, “No,” so, of course, he wouldn’t let us in. Then John came up and said, “Well, that’s our song,” and the doorman said, "Yeah, that’s what everybody says,” and he still wouldn’t let us in.

And then a voice from just inside the club said, “It’s all right, they’re friends of mine” - it was Paul who had already found the smartest club in town. He was there with Jane Asher and so we went in and had some drinks there. Then we went on to The Flamingo all-nighter, which was just finishing, and Georgie Fame came up and we introduced John and Ringo to Georgie Fame – he knew about them of course, and they knew about him – and amazingly, I think only one girl came up and said “Are you The Beatles?” So that’s how I met them originally and by the time I worked with them I knew them quite well.

The other link is that by then, they had become good friends with Robert [Fraser, who was Blake’s art dealer at the time]. Robert was a very good dealer. He was there right at the beginning of Pop Art and one of first people to bring in artists like Warhol and Oldenburg from the States, but on the other hand he was doing lots of drugs and probably supplying – via other people – The Stones and The Beatles. So as well as being my art dealer, he was probably their drug dealer. But he was a lovely, brilliant man. (Homage to Sonia Delauney, pictured above.)

The other link is that by then, they had become good friends with Robert [Fraser, who was Blake’s art dealer at the time]. Robert was a very good dealer. He was there right at the beginning of Pop Art and one of first people to bring in artists like Warhol and Oldenburg from the States, but on the other hand he was doing lots of drugs and probably supplying – via other people – The Stones and The Beatles. So as well as being my art dealer, he was probably their drug dealer. But he was a lovely, brilliant man. (Homage to Sonia Delauney, pictured above.)

Robert was advising Paul what art to buy and I think he took him to meet Magritte. Robert dealt with Magritte and got that little picture of an apple that says “I’m a pipe” or whatever, and took it to Paul’s house. Paul was busy so Robert left it on the table in the hall, this little picture for Paul to buy – Paul’s got about four Magrittes that he bought through Robert – and that’s where the idea for the Apple symbol [for Apple Records, The Beatles' record label] came from.

Anyway, originally the cover for Sgt Pepper had been designed by a Dutch design group called The Fool – they later painted the outside of the Apple Boutique in Baker Street – and it was all swirls of green and red and purple. Robert pointed out that it was just another psychedelic cover and suggested that one of his artists should design something – and he proposed that I did it, so we met up to discuss it.

They [The Beatles] already had this idea that Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band would be a German marching-band version of The Beatles and quite recently Paul showed me a drawing which he claimed he showed me at the time – perhaps he did – of a crowd of people. My main contribution was the idea of making a magical crowd that would be their fans and I asked them to make a list of their favourite people to include, so we ended up with everyone from Marilyn Monroe to Aleister Crowley. There’s a few of my ideas on there too – Dion of Dion and the Belmonts, Sonny Liston, Shirley Temple.

It was a lot of work just setting the whole thing up and then there were two weeks of physical work building the set in [photographer] Michael Cooper’s studio. We had cut-outs of all the people we were going to feature made of plywood and cardboard which were then photographically hand-coloured and fixed to the wall. A little stage was made with a sloping front and a flower bed in the front, except on the evening we put the flowers in – which were all fresh cut flowers - we had a phone call: “We can’t do it tonight, we’ve nearly finished a song and it’s more important to get on with that.” So all the flowers had to go back to go into fridges and be held for another day. But the next day they [The Beatles] turned up and there was a big party in the studio.

With the exception of That Lucky Old Sun for Brian Wilson, all the album covers you have done since Sgt Pepper seem to be for bands or performers who are somehow profoundly English – Paul Weller, Oasis, The Who, for example.

I know, they are, aren’t they? And it’s just chance but oddly enough most of them came to me via The Beatles. I mean Paul Weller is an enormous Beatles fan so he called me and asked me to do Stanley Road, which I was very excited about. Then, of course, the Gallagher brothers [Liam and Noel from Oasis] are both huge Beatles fans. They asked me to do an album cover [Stop the Clocks] but actually, up until then, all their covers had been almost recreations of Beatles albums. (Homage to Rauschenburg, pictured left.)

I know, they are, aren’t they? And it’s just chance but oddly enough most of them came to me via The Beatles. I mean Paul Weller is an enormous Beatles fan so he called me and asked me to do Stanley Road, which I was very excited about. Then, of course, the Gallagher brothers [Liam and Noel from Oasis] are both huge Beatles fans. They asked me to do an album cover [Stop the Clocks] but actually, up until then, all their covers had been almost recreations of Beatles albums. (Homage to Rauschenburg, pictured left.)

They already had an idea which was to use an image of a shop that used to be in the King’s Road called Granny Takes a Trip which famously had a painting on the blind. So they gave me that idea and I then put them in as if they were real people in front of the shop and we made it look as if there was graffiti, which was actually all the credits and information about the record. We were all finished and ready to go and when the man who used to own Granny Takes a Trip decided he was going to make an album himself and use exactly the same photograph - which he did – so that idea had to be dropped. So Liam came over, we talked about it, did a walk round the studio like we’ve just done and collected everything that he really liked - there was a big double dartboard which is now in the Museum of Everything and a locker that’s gone to the Waddington [Galleries].

Then I put the dartboard next to the locker and got some Punch and Judy figures and some other things that Liam had picked and arranged everything in the locker and on a table in front of the dartboard. My concept was to make up lots of potential myths, lots of things that could be turned into stories later on. So, for instance, when I put the Seven Dwarves on the shelf of the locker, I put five in the front and two at the back. That was simply because I couldn't fit them all in but I must admit, I also liked the idea that one day people might try to work out if there is any meaningful reason for Happy and Dopey to be at the back, separated by the others.

There is one tangible real myth, however, and that is that the little blue Snow White figure in the locker is also in the flower bed on Sgt Pepper. So that’s the only actual piece of mythology. And as references go, I think it’s rather appropriate.

- Homage 10 x 5 - Blake's Artists at the Waddington Galleries from 17 November until 11 December

- Find Peter Blake on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Comments

i am curious as to which

Does anyone know the location

Great concept for an exhibit