theartsdesk in Brussels: The EU Takes On Google | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Brussels: The EU Takes On Google

theartsdesk in Brussels: The EU Takes On Google

Translating books, linking museums and libraries - not as simple as it looks

This year the Eurozone is going to be the big political subject; fragmentation the looming concern. Culturally too, one would think that Europe, with 23 official languages, and another 60 minority languages spoken, is too much of a warren to be able to find any possible unanimity. But two ambitious projects are afoot in Brussels: to enable the translating of major literature across languages, and to join up all the museums, galleries and centres of knowledge in one great cultural cornucopia. And before you mutter that this is as exciting as sprouts, think for a moment of the implications - an online equivalent of a vast library of all the major known cultures, a gigantic linking of the great libraries, museums, galleries and universities in a single place for all humanity to access.

The two projects are both only in infancy, and neither is well known. And yet the moment you hear of them they become obvious. Given the globalisation of information technology, it does seem downright contrary for the leading books of so many great world cultures to be passing the other great world cultures by year after year, for lack of translation. And surely, when you can find the Louvre and the British Museum and the Cinecittà Luce and the University of Athens all online individually, it is the next step for you, the Scottish child, the Maltese pensioner, the Bulgarian schoolteacher, to be able to find them all linked up in one beautiful portal, accessible to all online, a grand gateway to European cultures?

While we welcome ever more non-verbal international art, we're ever more restricting our access to each others' books

How simple and desirable these aims sound - one of those genteel tea-time discussions you imagine Eurocrats settling down to over Cognac and Belgian chocolate snails on a sleepy afternoon after a power lunch discussing the Greek economic collapse or illicit cross-border migration into Germany.

Not so fast. For the licit movement of words across borders is an even more complex issue than the licit movement of workers and trade. And smuggling, curiously enough, is just as large and complex a problem, as I discovered unexpectedly on an illuminating trip last month to Brussels to hear more about European cultural initiatives.

The EU has a tiny little cultural budget - about 400 million euros shared over seven years between 35 countries, a sum not even close to what our Arts Council spends in a year here. Prioritising this, the EU has put communication at the heart of its simple culture agenda. While there are a few European grants handed out to the easy cultural travellers - the non-verbal performance arts groups like children's dance-theatre or puppets - the more valid and (to me) compelling projects are to straddle the language and culture barriers between countries by funding translation of literature and by digitisation of access to Europe's spectacular museums and libraries.

In the first case, we have taken for granted that the only second language required in day-to-day usage is English, and largely the world has agreed on that. But in a world joined up by instant electronic access, even the best-read of us has to confess we've read few (if any) good novels in their native German, Spanish, Swedish or French, let alone Macedonian or Lithuanian. Does it matter? Little Englanders might think it doesn't, but it's paradoxical and surely constrictive that while we welcome ever more and more non-verbal international culture (music, dance, visual art), we are ever more restricting our access to each other's books, films and music lyrics by our non-understanding of language.

We've all been stuck with the clunky surtitles and translations on Stieg Larsson's Lisbeth Salander films and novels, to take just one instance. At least we got the surtitles. In Latvia, Greece and Portugal, local viewers need good English to get the entertainment that millions of English readers and filmgoers have taken as a natural right.

The stumbling block is of course translation, and - in a tight publishing world - persuading publishers to take on the gamble of publishing major works in translation from other cultures. It particularly hits emerging contemporary voices.

By far the majority of translation is from English books, films, TV etc into other European languages, but only a tiny proportion in reverse. Translation of major novels or poetry, say, from Czech to Irish, or from Norwegian to Greek, remain mostly theoretical aims.

And then there is the question of how readable the translation is: should it be a literal word-for-word translation, ie entirely accurate to the meaning of the words the writer used, or a more creative and idiomatic version vitalised for the reader in the new language (as, say, the late crime novelist Michael Dibdin spoke of in theartsdesk Q&A)? In the area of poetry this is clearly a stumbling block, but even in prose the second may be a more desirable end, and it requires a translator of much greater gifts, more an interpreter than a transliterator.

All of which shows the complexity of the task the European Union set out to address in some way with its European Prize for Literature, an annual rotating award installed in 2009 where up to 12 countries a year will get to nominate a work of new fiction by a relatively unknown writer for which the EU will fund the translation, so as to tempt publication of it in another country.

The issue of the need for Europe to translate and cross-communicate its literature is one of those that depends very much from where you look at it. In Brussels we were told that a mere 1,600 foreign books have been published in translation into any other European language since 2007. Indeed that would appear particularly niggardly and narrow-minded of the dominant English publishing industry. Yet for some of the British books editors attending this trip to see the 2010 European Prize, the question was whether there was genuinely any need further to swell the cascade of books published weekly in the UK with less than top-drawer foreign imports. And yet again, for the Macedonian, Cypriot, Ukrainian, Icelandic and other foreign authors among the winners of this year’s translation prize, this opportunity was heaven-sent. Even to be published in one other country than their own would be a gigantic step forward.

At the prize-giving, Doris Pack, the Chair of the European Parliament’s Culture and Education committee, made the trenchant point that despite the richness of cultural exhibitions that circle the world, for every artefact and domestic pot on show there is hardly one written word. Without the linguistic expertise of top-class translators there is no bridge for books to cross from one language culture to another, from one era to another.

In 2011 - for the Prize’s third year - it will be the UK’s turn to nominate a new novel for translation abroad. I question why non-fiction and biography are excluded from the EU’s scheme (the latter I would have thought as valuable as contemporary fiction), and some of the UK publishing experts on the Brussels trip felt that both the name of the Prize is misleading (this is not, after all, a literature competition on quality) and its judgment criteria are unclear.

All the same, this translation prize is one of two notable schemes that only the EU could aim to do, and I think the second is truly a remarkable one. It is the digitising and linking of the major museums and galleries of Europe into a global cultural portal freely available to the public.

So far the Europeana website is a not very impressive-looking place, embryonic in function and in design, but with France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Germany already making great strides to join up, it has the potential indeed to become an epic online library of the arts as glorious as any of the legendary libraries of antiquity, and of course vastly more accessible.

So far the Europeana website is a not very impressive-looking place, embryonic in function and in design, but with France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Germany already making great strides to join up, it has the potential indeed to become an epic online library of the arts as glorious as any of the legendary libraries of antiquity, and of course vastly more accessible.

The project was instigated five years ago by a panicky realisation by political leaders that Google was changing the internet landscape, starting to digitise books and records, and altering completely the way the public searched for what it wanted to know. A monopoly was stealthily falling into place, and an opportunity might soon be lost to take control of cultural access for more altruistic motives.

The aim appears straightforward enough: to encourage all museums, galleries, libraries and archives to join the database and allow the world to see what they have. Scientific writings, classic literature, past contemporary work, out-of-print and ancient books, major newspapers, all of these are examples that once published on paper have a short shelf-life before vanishing into obscurity in libraries. Online digitising has the utopian possibility of restoring and conserving for tomorrow vast tracts of published thought and reportage thought lost.

The problems are massive, however. First, who pays? There are several candidates. The state who issues the national strategy, the participating museums and libraries, the digitising agencies, commercial operators (such as Google), or the end-user (you or me)?

The second, equally tricky, is the question of rights - who should own the copyright of a book 50 years out of print when it has been with cost, care and expertise digitised and restored to light by an outside agency? About 80 per cent of the cost of digitising is spent on simply researching the rights to it, for instance. The 20th-century literature boom is festooned with so many rights and access problems that the difficulty in selecting a comprehensive range for a digital global library is obvious. Paradoxically materials from the pre-19th and 21st centuries are much easier to deal with, being either out of copyright or formulated for the IT age.

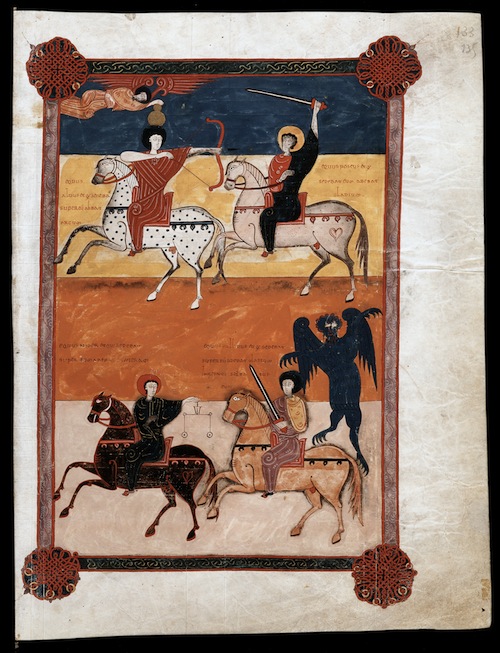

And if someone in France wants to reproduce Mary Queen of Scots’ last letter (in the National Gallery of Scotland) in their student thesis or newspaper article via Europeana, how and from whom should the gallery gather a reproduction fee to help in its conservation of future royal last letters? (Or royal SMS, for that matter.) Should it be freely available on Europeana like the eighth-century Spanish treasure, the Comentarios al Apocalipsis (pictured right)?

And if someone in France wants to reproduce Mary Queen of Scots’ last letter (in the National Gallery of Scotland) in their student thesis or newspaper article via Europeana, how and from whom should the gallery gather a reproduction fee to help in its conservation of future royal last letters? (Or royal SMS, for that matter.) Should it be freely available on Europeana like the eighth-century Spanish treasure, the Comentarios al Apocalipsis (pictured right)?

And take intellectual rights: should research scientists be obliged to let their raw data be published by their university, when other scientists might make potentially commercial use of it?

A third, even more thorny issue is: in what form can people agree on preserving it? Video, floppy disk and wax cylinder are all technologies long ago made redundant by technological changes. It's hard to conceive that those who dominate software today - the Microsofts and Sonys of this world - may be in 100 years' time as forgotten as His Master’s Voice and Vitagraph, but their dominance of consumer sales makes them the obvious dictators of the media by which this information needs to be transmitted now to the masses, and therefore the foreseeable future.

Finally: who is this all for? Denmark, for instance has restricted access to university offerings to Europeana to visitors with .dk domains only, effectively only Danes or Danish operators - which is unacceptable to the EU.

With all these problems lurking under the surface of what appears such a noble and uncontroversial cultural aim, it is possibly unsurprising to find that Britain has been far more reluctant to join in so far than France and Germany. Oxford University has linked its First World War poetry archive: the British Library has made some links, but nowhere near the wholesale scale desired. Many European countries have yet to get involved at all.

Where all this circles back to the books prize is that Google is at the forefront of development of web translation engines. Having funded and developed these to an ever-greater level of sophistication, it wants a return on its investment by controlling the rights of the translations made by its software, such as to allow users to access Europeana. Web translation software is moving so fast that many books for which the EU Prize is the only opportunity for translation right now will soon be able to be read in simultaneous translation by the viewer in any country.

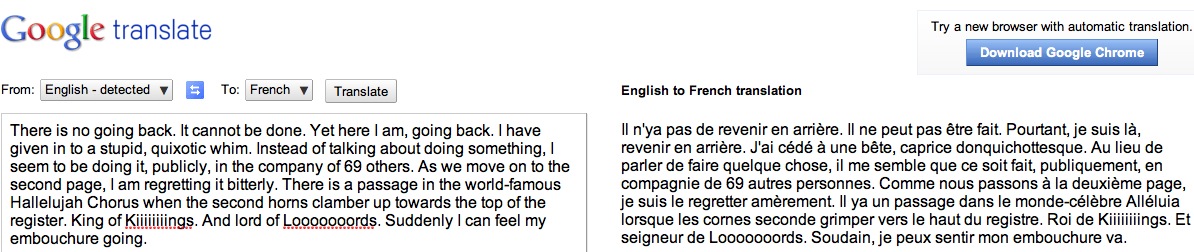

This, superficially, looks pretty marvellous, until you think of the control Google has over the process, by natural process. The languages available, for instance. The obvious linguistic horrors that this will certainly (temporarily at least) transmit like a contagion through usage. (See below how an extract from Jasper Rees's I Found My Horn turns, via Google Translate, into bad and deviant French:)

And the commercial/political side: would a Google-translated book be accessible only via the Google search engine? And thus in thrall to Google’s own business stratagems (a hot potato in countries such as China right now)? Private partners in any form of digitisation (which involves them paying for the technical, linguistic and other experts to formulate the programmes) naturally expect a return on their investment and a measure of control on the product. It now becomes clarion clear why the EU needs to act fast with a unison voice and in a very joined-up way.

Whatever happens in the European economic and fiscal areas, this is one cultural area - the translating of culture from country to country - where as in Aesop’s fable single sticks are useless by themselves, but bound into a bundle can become a force for everyone’s good. A very big stick in the form of Google already exists. Good or bad, it appears that the European Union sees this as likely to determine the direction of the future preservation of major European cultures. Who controls Google could, they fear, control access to culture for future generations.

In 2012 the European Commission is due to review how the Europeana project is going. Under the present timetable the best financial model should be agreed by next year, to ensure the online database of knowledge has a solid perpetual future. From 2011 to 2020 the agenda is to bring the entire European cultural heritage online in some comprehensive form available to European citizens.

One imagines that to get three dozen or more countries to agree will be a piece of cake compared to finding a method for authors, researchers, painters, art dealers, curators, translators and software tycoons to share their interests. But as a grand projet, it embodies all the very best aspirations to civilisation that the EU was set up for, as well as the most lethally unnavigable minefields.

- Find the Europeana website

- A European Literature Brainstorming meeting is being held on 25 January at Europe House, 32 Smith Square, London, involving publishers, editors and critics from the UK books industry who took part in this trip and want to discuss generating more liaison between them and other countries’ books industries. Contact Rosie Goldsmith rosiegold@tiscali.co.uk

Watch the Europeana website's trailer (no words, of course, all visuals and muzak)

{vimeo}15018411{/vimeo}

Share this article

more Visual arts

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Add comment