Rachel Whiteread: Drawings, Tate Britain & Gagosian Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Rachel Whiteread: Drawings, Tate Britain & Gagosian Gallery

Rachel Whiteread: Drawings, Tate Britain & Gagosian Gallery

The art of the thinker: drawings show the art behind the art

Rachel Whiteread is best known for her exploration of space, of presence and absence, of how we look at what is present – and absent – in the textures of our lives. House, her life-sized cast of a house in a derelict street in East London, first brought her to fame, and more recently Untitled (Plinth), her mockingly affectionate take on the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square, a resin-cast replica of the plinth itself, literally shaped a new viewpoint of that absence in the heart of the West End.

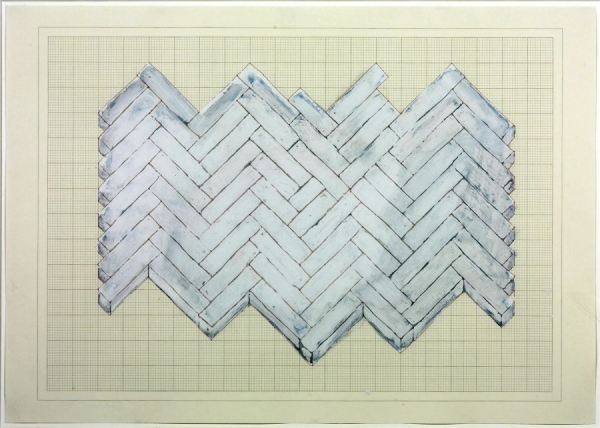

Now in two exhibitions of (mostly) drawings and some sculpture, the viewer can follow along, looking at what, in many cases, appear to be almost the blueprints of these more high-profile works. For if Whiteread's sculptures are imprints of other people’s lives, the drawings are, perhaps, traces of her own life, or at least thought-processes, as can be seen in the preparatory sketches, Study for House (main picture above).

The exhibition at Tate Britain is low-key, almost dreamlike in its slow unfolding. The early sections are divided by household objects: sections for "floors", "beds and mattresses", "doors, windows, switches", and "tables and chairs" (with a lovely resin sculpture in the centre, Table and Chair (Clear) (pictured right), where the chair - or more properly a stool - follows the outline of a gap in the table, but in proportion and depth then charts its own route, almost seemingly to set out perkily for a walk, leaving its larger progenitor behind. The colours of the drawings here are pastel-ey, low-key, with a strong linear focus, like descendants of Agnes Martin (pictured below).

The exhibition at Tate Britain is low-key, almost dreamlike in its slow unfolding. The early sections are divided by household objects: sections for "floors", "beds and mattresses", "doors, windows, switches", and "tables and chairs" (with a lovely resin sculpture in the centre, Table and Chair (Clear) (pictured right), where the chair - or more properly a stool - follows the outline of a gap in the table, but in proportion and depth then charts its own route, almost seemingly to set out perkily for a walk, leaving its larger progenitor behind. The colours of the drawings here are pastel-ey, low-key, with a strong linear focus, like descendants of Agnes Martin (pictured below).

The idea of descent is not an idle one: casts are, by definition, absences that mark where presence has once been. They are, in effect, the children of the original, just as the stool is a child of the table. The idea of descent, of cast-offs, continues in the section called "Village", with its naïve, flat gouaches of houses and streets, sketches that link to Place, Whiteread’s 2008 installation piece that so wonderfully filled a room at the Hayward: a ghost suburb, a dolls-house village, with all the fun and play removed: spaces for dying instead of spaces for living.

The idea of descent is not an idle one: casts are, by definition, absences that mark where presence has once been. They are, in effect, the children of the original, just as the stool is a child of the table. The idea of descent, of cast-offs, continues in the section called "Village", with its naïve, flat gouaches of houses and streets, sketches that link to Place, Whiteread’s 2008 installation piece that so wonderfully filled a room at the Hayward: a ghost suburb, a dolls-house village, with all the fun and play removed: spaces for dying instead of spaces for living.

The idea of small, complete worlds, however, is one that is carried through in Vitrine Objects, a new piece where objects, both found and made, have been collected by the artist and grouped in a display case. From shoes and shoe-objects – lasts, trees, soles – to pebbles, jars, toys, bits of string, jelly-moulds, casts of teeth, or light-switches, the whole detritus of life, of bits and pieces, of random and yet coherent series of objects somehow coalesce the two sides of Rachel Whiteread, in her trademark homely, yet slightly creepy.

For anyone who wants a clearer idea of the inner workings of Whiteread’s art, this is an exemplary exhibition. The show at Gagosian, in the West End, is a much lesser affair, a few drawings and a series of stools, made, unusually for Whiteread, from Portland stone, cement, and sandstone – outdoor, hard-wearing material instead of her more familiar plaster or resin. As always with Whiteread, the work is elegant and thoughtful, but this is very much a pre-selected show for buyers, not a viewing show that explores her art. The same cannot be said for two compact but fascinating shows at Annely Juda Fine Art, a few minutes’ walk from Gagosian, but a world away in spirit. Here David Nash, fresh from his triumphant retrospective at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, shows some new indoor wood pieces, which are very impressive. Even more impressive is the fact that a whole element to his work can be seen developing. For a long time Nash has produced broodingly black drawings of three basic shapes: triangle, cube and circle. Now he has moved on to extraordinarily bright versions, triptychs in red, yellow and blue, and from these, the viewer progresses to red panels (pictured above) – one, two or three at a time, framed in his signature charred black. Given their charcoal predecessors, the surprise is their radiant ability to capture an inner light, to create a sense of colour-ness. Furthermore, this show has cleverly been bookended by another artist, Lesley Foxcroft, who works not in Nash’s almost living natural woods, but in MDF: processed chipboard. Here she concentrates on elements of four, four boards, held by plain chromed washers and bolts, in an intensive exploration of the beauty of the straight edge, the classicism of a corner, all highlighted by the deceptive simplicity of this monochrome, manufactured pressed material.

The same cannot be said for two compact but fascinating shows at Annely Juda Fine Art, a few minutes’ walk from Gagosian, but a world away in spirit. Here David Nash, fresh from his triumphant retrospective at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, shows some new indoor wood pieces, which are very impressive. Even more impressive is the fact that a whole element to his work can be seen developing. For a long time Nash has produced broodingly black drawings of three basic shapes: triangle, cube and circle. Now he has moved on to extraordinarily bright versions, triptychs in red, yellow and blue, and from these, the viewer progresses to red panels (pictured above) – one, two or three at a time, framed in his signature charred black. Given their charcoal predecessors, the surprise is their radiant ability to capture an inner light, to create a sense of colour-ness. Furthermore, this show has cleverly been bookended by another artist, Lesley Foxcroft, who works not in Nash’s almost living natural woods, but in MDF: processed chipboard. Here she concentrates on elements of four, four boards, held by plain chromed washers and bolts, in an intensive exploration of the beauty of the straight edge, the classicism of a corner, all highlighted by the deceptive simplicity of this monochrome, manufactured pressed material.

While Whiteread focuses on what is not there, the shapes that are left once presence is removed, so Foxcroft illuminates our sense of limits and borders: where and why space is delineated as it is. Both of them are concerned with the built, the manufactured world, the world of cities and industry that we live in, and how we perceive these manufactured places. And then, sandwiched between these two fine artists is David Nash. Moving to the rhythm of the natural rather than the built world, he is the rich, thick, deep organic filling between the constructed realities of the Whiteread and Foxcroft.

While Whiteread focuses on what is not there, the shapes that are left once presence is removed, so Foxcroft illuminates our sense of limits and borders: where and why space is delineated as it is. Both of them are concerned with the built, the manufactured world, the world of cities and industry that we live in, and how we perceive these manufactured places. And then, sandwiched between these two fine artists is David Nash. Moving to the rhythm of the natural rather than the built world, he is the rich, thick, deep organic filling between the constructed realities of the Whiteread and Foxcroft.

- Rachel Whiteread: Drawings at Tate Britain and Gagosian

- Find Rachel Whiteread on Amazon

- David Nash and Lesley Foxcroft, at Annely Juda Fine Art

Share this article

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment