Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, V&A | reviews, news & interviews

Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, V&A

Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, V&A

Ten spectacular new rooms covering 1,300 years of European art, design and architecture

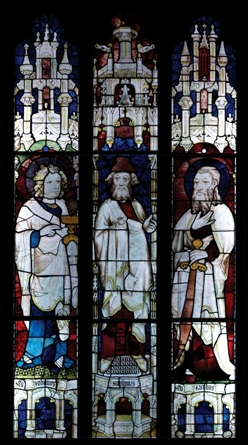

Covering the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the conclusion of the High Renaissance in 1600, the galleries offer a compelling journey. It begins, in fact, where the story ends, with a themed display called the Renaissance City. Here you’ll find 16th-century Italian street lamps, walls studded with highly decorative chunks of building masonry, garden statuary, richly ornamented sculptural altarpieces, elaborately carved fountains, tomb effigies and stained glass (stained-glass figures from Winchester Cathedral, pictured above). If you climb to the balcony and view the panoramic display from above, it's possible to appreciate just how beautifully this has all be arranged: all clean lines and spacious geometry, it’s astonishing how so many objects can be arranged without inducing an overwhelming sense of clutter and confusion.

Covering the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the conclusion of the High Renaissance in 1600, the galleries offer a compelling journey. It begins, in fact, where the story ends, with a themed display called the Renaissance City. Here you’ll find 16th-century Italian street lamps, walls studded with highly decorative chunks of building masonry, garden statuary, richly ornamented sculptural altarpieces, elaborately carved fountains, tomb effigies and stained glass (stained-glass figures from Winchester Cathedral, pictured above). If you climb to the balcony and view the panoramic display from above, it's possible to appreciate just how beautifully this has all be arranged: all clean lines and spacious geometry, it’s astonishing how so many objects can be arranged without inducing an overwhelming sense of clutter and confusion.

This is just as well since, in all, there are 1,800 works of art, artefacts and rare treasures on view, displayed in ten galleries, arranged on three floors, and taking up one entire wing of the museum. It is the final phase of part one of the V&A’s extensive “future plan” overhaul. This part of the reconstruction cost £30m (two thirds of which was privately raised, the rest coming from the Heritage Lottery Fund). It has been seven years in the planning and the clever design of the galleries, by architects MUMA in collaboration with V&A curators, lends coherence to a story that lifts the medieval era from the so-called Dark Ages, blurring the division with the Renaissance.

It all feels seamless. But be warned, it‘s impossible to consume it all in one visit. Several carefully paced ones would allow you to take each gallery in turn as a mini-exhibition in each itself.

It all feels seamless. But be warned, it‘s impossible to consume it all in one visit. Several carefully paced ones would allow you to take each gallery in turn as a mini-exhibition in each itself.

The V&A has the largest collection of Italian Renaissance sculpture outside Italy, and in this first display you’ll encounter Giambologna’s famous marble statue, Samson and a Philistine (1560, pictured above). These two violently writhing figures add a sense of furious energy and drama to a display that might otherwise feel calmly contained. A modern waterfall just behind Giambologna’s sculpture creates an otherwise soothing ambience, turning your visit into a leisurely walk through a well-appointed Renaissance garden or courtyard.

This section concludes with the huge choir screen, featuring three sturdy Roman arches, from the Cathedral of St John at ‘s-Hertogenbosch (1610-13), in the Netherlands, and leads through to the altarpieces of Northern Europe.

There are too many highlights to recount, but particularly worth mentioning is the section devoted to Donatello, the Florentine accepted as the greatest sculptor of the Quattrocento. It’s evident here how a work such as Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1455-60), in which Mary Magdalene expresses her raw grief by pulling at her hair while St John cradles his head in despair, was really one of the first to bridge the stylistic divide between the late medieval period and the Renaissance. Compare a painting of the Virgin and Child by Crivelli from around 1480, some 40 years later, and you see a much more stylised work of art (pictured above).

There are too many highlights to recount, but particularly worth mentioning is the section devoted to Donatello, the Florentine accepted as the greatest sculptor of the Quattrocento. It’s evident here how a work such as Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1455-60), in which Mary Magdalene expresses her raw grief by pulling at her hair while St John cradles his head in despair, was really one of the first to bridge the stylistic divide between the late medieval period and the Renaissance. Compare a painting of the Virgin and Child by Crivelli from around 1480, some 40 years later, and you see a much more stylised work of art (pictured above).

The V&A is also particularly rich in English alabaster sculpture, a material which was cheaper and more readily available than marble. In one glass display you’ll find a small head, with blackened lips and dead eyes, of Saint John the Baptist. Though also found in churches and guildhalls, heads of St John were especially popular in English homes in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, just as crucifixes would be later. And talking of an Englishman’s home, we even have part of a fine example here: a carved oak façade of a Tudor house (pictured above). The Bishopsgate home of one Sir Paul Pindar, an exceptionally wealthy merchant, is a rare surviving example of London architecture before the Great Fire.

The V&A is also particularly rich in English alabaster sculpture, a material which was cheaper and more readily available than marble. In one glass display you’ll find a small head, with blackened lips and dead eyes, of Saint John the Baptist. Though also found in churches and guildhalls, heads of St John were especially popular in English homes in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, just as crucifixes would be later. And talking of an Englishman’s home, we even have part of a fine example here: a carved oak façade of a Tudor house (pictured above). The Bishopsgate home of one Sir Paul Pindar, an exceptionally wealthy merchant, is a rare surviving example of London architecture before the Great Fire.

Social and political history is threaded through this compelling story of Western art, and in visual terms, you really couldn’t hope to find a better telling of it anywhere else.

The Medieval and Renaissance Galleries at the V&A are on permanent display. For more information visit the V&A website

A wider selection of the exhibits can be seen in theartsdesk gallery

more Visual arts

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Add comment