Ivor Abrahams, Mystery and Imagination, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Ivor Abrahams, Mystery and Imagination, Royal Academy

Ivor Abrahams, Mystery and Imagination, Royal Academy

A print show that is tart and sweet, small but perfectly formed

In this month of royal weddings, endless bank holidays and (possibly?) equally endless good weather, it can be hard to focus, so perhaps this is the perfect opportunity to catch up with a show that nearly got away. Instead of winsome blockbusters like Tate Modern’s Miró, or the V&A’s The Cult of Beauty, Ivor Abrahams' print show is tart as well as sweet, small but perfectly formed, the ideal restorative after too much sugar, whether in wedding cakes or art galleries.

Ivor Abrahams is perhaps better known as a sculptor, studying under Anthony Caro in the 1950s, and first exhibiting, with Peter Blake, in the 1960s. Both of these artists seem to impinge on this print show, in delightfully unexpected ways.

Two literary sources are the jumping-off point for Abrahams here: Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales and Poems and Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. At first, there does not appear to be much to link the two: Burke’s work first appeared in 1757, Poe’s more than 75 years later; Burke’s is a philosophical treatise, Poe’s are literary explorations of the uncanny, the odd and the mysterious.

The prints with the overall appellation To Edmund Burke (1978-9) have no titles, but a panel of quotations from Burke’s work appears beside them. These indicate that the individual prints are not illustrations, but are created as a whole to encompass the moods of Burke’s work. The key citation would appear to be: “No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear.” This, surely, is the link between the two series, for Poe’s work hovers around fear like wasps around some jam.

Yet oddly, while fear, uncertainty, grief, longing and mourning are all clearly the starting points for Abrahams, the prints themselves are wonderfully serene. They encapsulate the emotions almost literally, sealing them in via Abrahams' own lyrical skills and his measured and yet lush use of colour. The 20 Poe screenprints recapitulate the stories in a similar way. Those familiar with Poe’s tales and poems will be able to pick out elements – here, the raven, there, the prematurely buried figure. But while this time Abrahams does give us clues, by using Poe's titles for each image, these are not literal, or illustrative, renditions, but once again appear to be mood-influenced reveries.

The 20 Poe screenprints recapitulate the stories in a similar way. Those familiar with Poe’s tales and poems will be able to pick out elements – here, the raven, there, the prematurely buried figure. But while this time Abrahams does give us clues, by using Poe's titles for each image, these are not literal, or illustrative, renditions, but once again appear to be mood-influenced reveries.

Trompe-l’oeil depth and verisimilitude are used to remarkable effect in some of the prints. The Premature Burial has a white tomb-shaped box, without actually being either a tomb or a coffin; yet it is rendered in sharply realistic detail, which gives a vertiginous yes/no reading. Do we know what this box is? The trompe-l’oeil effect tells our eyes we must know, while our brains record that it is in fact left undefined. The dark-red fabric caught in the opening, therefore, gains a sense of foreboding because of the unresolved nature of our vision.

A Dream Within a Dream (main picture, above) has a Magritte-ish sense of illusionism too: in the top half, sand runs through the hour-glasses, warning that the end is at hand; on the bottom level, however, the sand illusionistically sits at the "wrong" end for gravity to be functioning. The same push-pull once again is neatly effected by Abrahams, once again wrong-footing the viewer.

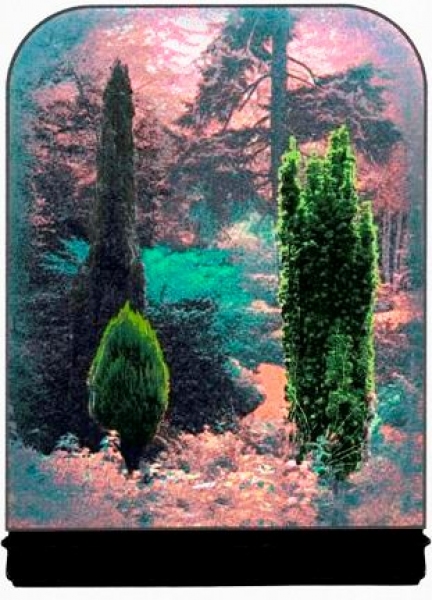

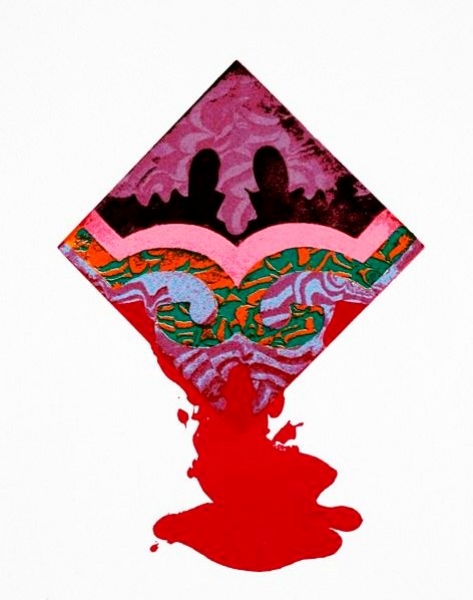

Everything has the air of a dream yet, strangely, given the iconography, they are dreams without menace. Domain of Arnheim (pictured above, right) is a lush secret garden, yet in the "wrong" colours, pinks and saturated greens blending and creating a hypnotic pattern that makes one believe, none the less, that this is what has always been, as one does in a dream. Even one of Poe’s most terrifying stories, The Masque of the Red Death becomes a symbolic, but not frightening, image (pictured left), a triangle of beautiful pattern spilling yet more beautiful blood.

Everything has the air of a dream yet, strangely, given the iconography, they are dreams without menace. Domain of Arnheim (pictured above, right) is a lush secret garden, yet in the "wrong" colours, pinks and saturated greens blending and creating a hypnotic pattern that makes one believe, none the less, that this is what has always been, as one does in a dream. Even one of Poe’s most terrifying stories, The Masque of the Red Death becomes a symbolic, but not frightening, image (pictured left), a triangle of beautiful pattern spilling yet more beautiful blood.

There is claustrophobia here, but such intense lyrical beauty that it is impossible to be oppressed. For while Burke’s notions of the terrible and the sublime may be oppressive, as in Abrahams' image of the headless, armless, high-heeled woman running endlessly, yet once in Poe’s vivid world, instead of the terrible, a terrible beauty is born.

- Ivor Abrahams: Mystery and Imagination at the Royal Academy until 22 May

Find Ivor Abrahams on Amazon

Find Ivor Abrahams on Amazon

Share this article

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment