Egon Schiele, Richard Nagy Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Egon Schiele, Richard Nagy Gallery

Egon Schiele, Richard Nagy Gallery

Women made of bones and bruises and heart in this superior show

Richard Nagy's gallery has said that they don't want millions of people rushing to see their show of Egon Schiele's drawings of women - it's only a small second-floor space on New Bond Street after all, and 50 fragile pictures crowd the walls. But don't let that dissuade you from seeing one of the shows of the year.

Schiele instantly summons up consumptive young women, déshabillées, angular, all the colours of livid bruises. His pencil marks are as sharp as the malnourished women's ribs. This show, however, shows why he was able to turn tawdry subject material into transporting art.

The works, executed between 1910 and his death, aged 28, in 1918, begin with the pictures which define him: Reclining Nude in Violet Stockings (1910) lies with her legs open and her head cut off (by the page). This realistic approach is all the more shocking for its rejection of the Classical nude, with their comely bellies, breast and thighs and depilated crotch. If Ian McEwan's hero of On Chesil Beach was put off his wife by a stray pubic hair, Schiele's drawings would have caused him to be committed. The beauty is in the unsparing detail.

One of the best early pieces is Woman With Homunculus (1910). A stumpy orange figure clings to a woman in stockings facing away, her head turned to look obliquely over her shoulder at you. As well as the erotic charge of the coquettish woman, the rendering of her skin, with broad blunt grey watercolour strokes, is almost Cubist in the way it catches a hundred different rays of light hitting her. Another masterwork is 1912's Reclining Woman and Standing Nude, where one woman in red bloomers lies across the page while another leans over her. The use of space, one woman disappearing behind another in three dimensions, rivals Cubism once again, without any of its distortions.

These are all well-established facets of Schiele's genius - the realism and the eroticism, the fleshy pallor and the gaudy clothes and the bony splayed hands. There is sensuality but not much human sensitivity, or at any rate much of a connection between model and artist - the women are anonymous and their faces are frequently clown or doll-like, blobby or deformed, as if he hated them or just couldn't be bothered.

These are all well-established facets of Schiele's genius - the realism and the eroticism, the fleshy pallor and the gaudy clothes and the bony splayed hands. There is sensuality but not much human sensitivity, or at any rate much of a connection between model and artist - the women are anonymous and their faces are frequently clown or doll-like, blobby or deformed, as if he hated them or just couldn't be bothered.

For all the (visually) decapitated women, there is a sensitive streak in the crayon and charcoal line drawings of the last couple of years of his life, before the Spanish flu took his wife and, three days later, him. He uses the same techniques as in his gouache and watercolour pictures, depicting etiolation and undress as ever, making inventive use of space and foreshortening, but the pictures feel all the more direct, his thoughts and intentions visible in the thickness and the weight of the lines.

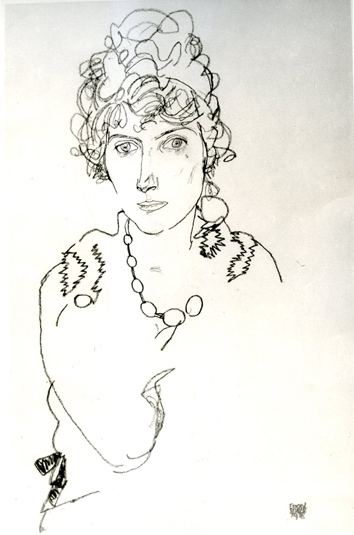

These pictures extend his emotional range beyond "sexy" and "indifferent". Women's eyes start to express feelings, especially in Edith Schiele (née Harms) (pictured above: private collection, courtesy of Richard Nagy Ltd, London), a picture of his wife from 1918, with a softness under the scribbled pile of hair and above the barely sketched body. Although he is no Raphael in drawing, Schiele brings out his tenderness in these lines. He still captures the erotic instant, but here are humour, mischief, sympathy. We see Schiele looking at women in many more ways than we are used to.

The earlier nudes are undoubtedly what he will be remembered for, but this exhibition makes a good claim for Schiele the human as well as a great claim for Schiele the artist.

- Egon Schiele at Richard Nagy Gallery, 22 Old Bond Street, until 30 June

Find books about Egon Schiele on Amazon

Find books about Egon Schiele on Amazon

Share this article

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment