Darren Almond: The Principle of Moments, White Cube Mason's Yard | reviews, news & interviews

Darren Almond: The Principle of Moments, White Cube Mason's Yard

Darren Almond: The Principle of Moments, White Cube Mason's Yard

A romantic visionary laced into the tight corset of artistic decorum

Facts about Norilsk speak for themselves. In winter, darkness prevails for six weeks and temperatures can plummet to -58 degrees C; snow storms rage 130 days of the year and snow covers the ground for some 270 days. Yet 135,000 people live in this Arctic Circle wasteland. What draws them? Mineral deposits.

In 1935 Stalin began sending hapless prisoners to work in the nickel, copper, cobalt and coal mines; by 1956 nearly 17,000 had died from the harsh realities of the gulag and forced labour continued until 1979. Although today’s miners receive good wages, environmentally the conditions are atrocious. Nickel smelting has turned Norilsk into one of the most polluted cities on the planet. Acid rain has killed all the trees, the air is filled with poisonous smog and the soil impregnated with platinum and palladium in concentrations high enough to be worth mining.

Perhaps to prevent journalists from writing shock-horror stories about this appalling scenario, in 2001 Norilsk was closed to all foreigners except people from Belarus, who are presumably the poor sods working in the mines. This must be why Almond kept his prying lens away from the city, the mines and the smelting plant to produce a somewhat oblique commentary on this harsh environment.

Those who remember his video Bearing (2008) – an in-your-face recording of a miner toiling up and down the slopes of a volcanic crater in Java carrying lumps of sulphur in flimsy baskets – may be disappointed by the low-key timbre of the new work which focuses on links between the mines and the outside world. Perhaps in anticipation of this response and to compensate for the absence of a human protagonist, Almond has ramped up the emotional temperature of the piece by resorting to special effects.

A single track railway runs from the mines to the port of Dudinka on the Yenisei River. Filmed in monochrome, the view along the track is blurred by flurries of snow hurled against the lens by relentless winds. Flanking the line, a row of telegraph poles stand sentinel, like empty gallows. Using the track as a roadway, a van passes by its headlights feebly probing the freezing gloom. Nothing else braves these dangerous conditions; we are alone.

This bleak meditation on our will to survive inhospitable circumstances would be powerful enough by itself, but it is accompanied (on two adjoining screens) by footage shot from on board an icebreaker as it opens up a channel along the Yenisei River. The images have been flipped into the negative so that as the frozen surface heaves and cracks, the ice appears black and the water welling up between the slabs glows with the demonic ferocity of molten lava or white hot glass. This heightens the dramatic impact, but lessens the work’s emotional resonance; by opting for greater immediacy, Almond has sacrificed longevity. The desolation of this Arctic region needs no ramping up; it already induces dread.

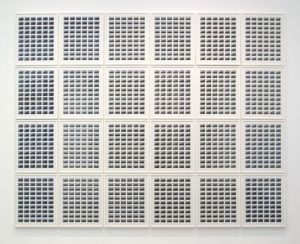

The ground floor gallery looks as if it is lined with filing cabinets. Emphatically covering the walls are panels of small photographs mounted behind cream pass-partouts and incarcerated in cream frames that create an insistent grid (pictured right). Peer into the succession of tiny images and you see a small town nestling among green fields beside a cliff top over which plummets a waterfall. Sometimes a mountain is visible in the distance, but more often it is obscured by cloud, mist and rain as the weather closes in.

The ground floor gallery looks as if it is lined with filing cabinets. Emphatically covering the walls are panels of small photographs mounted behind cream pass-partouts and incarcerated in cream frames that create an insistent grid (pictured right). Peer into the succession of tiny images and you see a small town nestling among green fields beside a cliff top over which plummets a waterfall. Sometimes a mountain is visible in the distance, but more often it is obscured by cloud, mist and rain as the weather closes in.

Almond photographed this bucolic scene every minute over the course of a week spanning the longest day, when it remains light all night, to create a 24-hour catalogue of the changing weather. The result is profoundly paradoxical. Images capturing the evanescent beauty of ephemeral happenings are incarcerated within the confines of a rigid display; ungovernable phenomena are thereby tamed and stifled by the uniformity of repetitive elegance.

Almond seems as keen to establish himself as a minimalist as to record the transitory effects of changing light. It's as though a romantic visionary had laced himself into the tight corset of artistic decorum, so as to appear seriously hard core.

- Darren Almond: The Principle of Moments at White Cube Mason’s Yard until 2 October

more Visual arts

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Add comment