On the Move: Visualising Action, Estorick Collection | reviews, news & interviews

On the Move: Visualising Action, Estorick Collection

On the Move: Visualising Action, Estorick Collection

Riveting exploration of the body in motion curated by Jonathan Miller

When we look at still images of moving figures what we see is not exclusively determined by what is in front of our eyes but what we already know about the world. If we stopped to think about this, it would seem obvious. We would know, for instance, that the putti who are so joyously leaping, dancing and bounding about in Donatello’s static frieze Cantoria would make little sense to us if we didn’t already know what such static postures implied: still images of moving figures can only come alive in the imagination when we have some understanding of how living bodies move, and of what comes before and after.

But as this enthralling exhibition, curated by Jonathan Miller and exploring the representation of movement in art and photography, reminds us, we often make inferences about the movement of living bodies that are based not on what we can directly observe, but on what we can only guess at. Just take a look at the opening work in this exhibition: A Race on the Round Course at Newmarket by 18th-century artist John Wootton (pictured above, courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). With two legs on the ground and two in the air, the creatures are each depicted in a “rocking-horse” gallop which, to our post-photography gaze, now lends the painting a rather comical air.

But as this enthralling exhibition, curated by Jonathan Miller and exploring the representation of movement in art and photography, reminds us, we often make inferences about the movement of living bodies that are based not on what we can directly observe, but on what we can only guess at. Just take a look at the opening work in this exhibition: A Race on the Round Course at Newmarket by 18th-century artist John Wootton (pictured above, courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). With two legs on the ground and two in the air, the creatures are each depicted in a “rocking-horse” gallop which, to our post-photography gaze, now lends the painting a rather comical air.

It was only after Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering experiments in stop-start photography in the 1870s, and his sequential arrangement of frames, that we learn the mysteries of horse locomotion, and finally see what the camera lens could pick up but the naked eye could not: that there was a moment when all four hooves are in the air, confirming the widely dismissed notion of “unsupported motion”, and that, furthermore, each leg has independent movement. This proved a timely revelation for Degas, whose paintings of the same period show his love of the racecourse.

But just as cameras can reveal the truth, so they can also hide it. As we see here, Muybridge was not averse to doctoring his sequences, swapping shots within each sequence and repeating others for a more aesthetically pleasing effect. If we look very closely at a sequence showing a female nude decorously picking up a handkerchief we find that one frame is repeated between one other shot, perhaps, in this case, to make up an equal number of frames which are double-stacked for display.

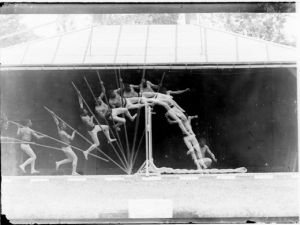

With Muybridge we don’t get unadulterated science, unlike the efforts of the lesser-known but brilliant Etienne-Jules Marey, a French contemporary of Muybridge‘s and, to Jonathan Miller, the real hero of the experimental photography of motion. As a young doctor, Marey had published on the subject of what he referred to as the “hydraulics of circulation”, before going on to devise an instrument that recorded the continuous variations of the radial pulse. In 1867 he turned his attentions to the movements of both the animal and human body, eventually pioneering the split-second frame. Rather than showing just one image per frame, split-second photography depicted a continuous sequence of images in one frame, so that we follow the elegantly overlapping arc of a pole-vaulter (pictured above, courtesy of the Collège de France), the flight of a bird and a running soldier. Marey was especially influential to the Italian Futurists who, in representing action, came to believe in the persistence of vision - that is, how our eyes could not eradicate different images rapidly succeeding one another. This is the basis of cinema, though the theory, as Miller explains, has its flaws and limitations.

With Muybridge we don’t get unadulterated science, unlike the efforts of the lesser-known but brilliant Etienne-Jules Marey, a French contemporary of Muybridge‘s and, to Jonathan Miller, the real hero of the experimental photography of motion. As a young doctor, Marey had published on the subject of what he referred to as the “hydraulics of circulation”, before going on to devise an instrument that recorded the continuous variations of the radial pulse. In 1867 he turned his attentions to the movements of both the animal and human body, eventually pioneering the split-second frame. Rather than showing just one image per frame, split-second photography depicted a continuous sequence of images in one frame, so that we follow the elegantly overlapping arc of a pole-vaulter (pictured above, courtesy of the Collège de France), the flight of a bird and a running soldier. Marey was especially influential to the Italian Futurists who, in representing action, came to believe in the persistence of vision - that is, how our eyes could not eradicate different images rapidly succeeding one another. This is the basis of cinema, though the theory, as Miller explains, has its flaws and limitations.

Still, as we see here, the paintings of the Futurists closely followed these developments to convey the dynamism of modernity, with Giacomo Balla’s Hand of the Violinist, Boccioni’s Dynamism of a Cyclist, and best of all - though, alas, we only have a photograph of the painting here - Balla’s wonderfully comic Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (surely the only Futurist work of art to show that this disagreeable bunch of proto-Fascists, with their mad manifestos, may have had a sense of humour after all).

But for me, one of the most remarkable images in this show, for its historic value if nothing else, has no movement in it at all. It is Louis Daguerre’s View of the Boulevard du Temple, Paris, and it’s the very first photograph featuring a person. Taken in 1839 (or perhaps as early as 1838), the image shows an apparently empty boulevard dominated by imposing buildings. Though the noon-day street would have been bustling with activity and human traffic, the only figure that is clearly discernible is the tiny image of the gentleman having his shoes shined; he was the only person who had stood still long enough to be recorded, for a lengthy exposure on sensitive silvered plates would have precluded anything on the move. Otherwise the scene looks like one of eerie abandonment (although we can, in fact, also just about discern a dark, much less distinct figure of the shoe-shine boy, who is seated). So there we have it, lies and truth in one medium.

As well as providing a compelling history of the development of the photography of movement, On the Move also raises fascinating questions about the physiology of seeing, and I would recommend reading Miller’s illuminating catalogue essay further exploring some of the concepts raised. Prepare to be taken on a moving journey.

On the Move: Visualising Action at the Estorick Collection until 18 April

more Visual arts

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Add comment