Q&A Special: Magician Paul Kieve | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Magician Paul Kieve

Q&A Special: Magician Paul Kieve

The illusionist on turning tricks for Harry Potter, Lords of the Rings and now Ghost

Hollywood has turned the special effect into a birthright for a generation of movie-goers. “How did they do that?” is no longer a question you hear in the multiplex. In the theatre it’s another thing entirely. Whatever the reception for the show in its entirety, the musical version of The Lord of the Rings did contain one remarkable illusion in which Bilbo Baggins vanished before the audience’s eyes. Even Derren Brown had no idea how it was achieved. The architect of that effect, and countless others in a long career in the theatre, was Paul Kieve.

Kieve’s newest challenge is also his most outlandish yet. Ghost, the film which starred Patrick Swayze as a murder victim who talks to his widowed wife (Demi Moore) through a medium played by Whoopi Goldberg, has been turned into a musical. The film version had visual effects galore to establish that Swayze’s character was no longer of this world. His hand passed through objects he couldn’t pick up. He could shove a coin invisibly up a vertical surface. How do you do that on stage? It’s not the first time director Matthew Warchus has called Kieve. They first worked together on Volpone at the National Theatre in 1995.

If such a thing as a conventional illusionist’s career exists, Kieve (b 1967) has not had one. Growing up in Essex, he was obsessed with tricks and he got his first break at 16 when he was hired to do a card trick on Sade’s debut video “Your Love is King”. At 19 he formed a double act called the Zodiac Brothers, which lasted for four years and took him all over the world. After an acrimonious split, Kieve conceived a plan to escape to university, but made it as far as the Theatre Royal Stratford East where he was asked to produce the effects for The Invisible Man. He has been working in theatre ever since.

At Kieve’s home in Hackney, the shelves of a tall cabinet groan with books about magic. One of those books is by Kieve himself. Although he all but made himself disappear when he joined the theatre, he wrote a history of magic in 1997 which took him out on the book festival circuit. His Hocus Pocus lecture turned into a small portable show which he sometimes still produces from the hat. But mostly he is in hiding. Other invisible gigs include being the only actual magician ever to work on the set of a Harry Potter film. Now you see him, now you don’t. He talks to theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: We need to establish the parameters with interviewing a magician. All the questions you really want to ask won’t get answered. Do you find that a frustration, that you’re not allowed to talk about the tricks of the trade?

PAUL KIEVE: There’s a couple of points there. I suppose I am a magician or an illusionist. I am in the magic circle but of course I spend most of my time on the backstage side of it. I’m creating stuff that is used in theatre and films. I think that’s not a coincidence and it ties in with this thing about secrecy and this seemingly anachronistic idea that you can keep things secret, which you can’t really any more with the internet. I don’t bow to any of its rules at all. In a way I reveal secrets all the time. When I work on a show I’m having to share and explore the methods with dozens of people in order to make the thing work. I suppose that’s what allows me to do, therefore, things that haven’t been done or seen or are more exciting if I was doing my own act. A friend of mine in America says, “Magicians guard an empty safe,” which I think is true. When you look at the secrets on their own they’re not terribly exciting. It’s not nuclear science. We’re talking about some quite simple things. In a sense my job is panning for gold where you’re trying to make it simpler, extract extraneous stuff, not overcomplicate it and make the method as simple as possible in order to make the effect.

PAUL KIEVE: There’s a couple of points there. I suppose I am a magician or an illusionist. I am in the magic circle but of course I spend most of my time on the backstage side of it. I’m creating stuff that is used in theatre and films. I think that’s not a coincidence and it ties in with this thing about secrecy and this seemingly anachronistic idea that you can keep things secret, which you can’t really any more with the internet. I don’t bow to any of its rules at all. In a way I reveal secrets all the time. When I work on a show I’m having to share and explore the methods with dozens of people in order to make the thing work. I suppose that’s what allows me to do, therefore, things that haven’t been done or seen or are more exciting if I was doing my own act. A friend of mine in America says, “Magicians guard an empty safe,” which I think is true. When you look at the secrets on their own they’re not terribly exciting. It’s not nuclear science. We’re talking about some quite simple things. In a sense my job is panning for gold where you’re trying to make it simpler, extract extraneous stuff, not overcomplicate it and make the method as simple as possible in order to make the effect.

The thing about magic that is difficult to grasp is the effect that sometimes quite simple methods can have if they’re placed in the right way. Taking a very classic illusion, sawing a woman in half, it just happened to catch the public imagination at that time because of the suffragettes. Something about that plot people wanted to see. Nowadays you can’t do the same thing but if you put magic into a story and people care about the story then I think it makes it a whole other thing. Magic can be so removed it can, at its worst, become a puzzle. When it’s part of a story at the end it shouldn’t matter about the methods or how they’re being done. Having said that, I’m not going to tell you how they’re being done.

When I explain to the cast and crew that the idea is to keep the secrets within the show, sometimes they’re like, “Oh God, what’s this guy going on about?” And then by the time we’ve finished weeks later perfecting this bloody thing after spending hours and hours getting the lighting right and the timing and the script, they understand why it’s not just a matter of going, “Oh, it’s a bit of thread that does this from the side.”

Can you do much more because of computers and more sophisticated lighting as when you did The Invisible Man?

When I did Invisible Man at Stratford in the early Nineties we didn’t necessarily even have the budgets for the big lighting rigs then. Lighting technology has made things possible in a precise way that wouldn’t have been possible when I was starting out. I don’t think it makes them simpler. It means that I can be a bit bolder with how things are lit. It’s a bit of a mixed blessing because some of these moving lights have much more of a tendency to blow, much more than the static lights. Originally you’d have to hang up a light for a special and that would be the only time it would be nice, whereas now they’re used all the way through the show. There’s more of a chance that when they get to your bit, which is the 190th cue, they’re not actually there. That can be a different problem. But in terms of technology, I’m using everything from absolute state-of-the-art automation and lighting to stuff that originated in the 1860s. I’m constantly looking back in order to get stuff that hasn't been seen now. Some of the effects in Ghost have been tremendously exciting to develop because some of them have not been seen in any form for over 100 years. And the form that they are in in Ghost is very, very different. (Pictured below, Richard Fleeshman, Sharon D Clarke and Caissie Levy in Ghost. Production images by Sean Ebsworth Barnes.)

Are you able to supply an example?

Are you able to supply an example?

We do things that I would say are in the realm of optical magic. If you think of an actor like Paul Daniels, they’re doing comedy magic and card tricks which is all fantastic stuff. But in a magic trick you rarely see things happen before your eyes. A lot of what happens is suggested. A lot of magic is about imagining what’s happening. Even the original version of sawing a woman in half, the girl was tied into a box and roped in and the ropes were held outside the box and the box was sawn through with a giant saw. The point the saw went through the box you couldn’t see any of the woman. You knew she was in there and you had seen the ropes tied around her wrists so what was happening? Was the woman being sawn in half in your imagination? All the information led up to the fact that there was only one conclusion: it’s either impossible or there’s a girl sawn in half.

Some of the things we do in Ghost you actually see the thing happen. You see someone materialise in front of your eyes and you see someone try and pick up an object and their hand does pass through it. You really see somebody passing through a door that’s solid and you’ve seen it’s solid earlier in the scene. If you’re doing that in a magic show, for example, walking through a door, you’d get two people up from the audience and they’d examine the door and they’d put the door in a big frame and you’d probably hang a curtain over it so you could see the outside of the door but not the bit you walk through, and you’d go through the middle of it and you’d take the prop away and they would come in and the door would still be solid. The point when you walk through the door, you wouldn’t actually see the flesh passing through the door. That’s a film effect. You don’t do that on stage. What we’ve tried to do in Ghost is to deliver those things as if you’re seeing them in a film. And not to be clever about it, but to make it a seamless part of the storytelling. But what’s surprising is you can do things that you see absolutely every day in films without any question. You don’t even think about it because you know it’s an effect and it’s just part of the storytelling. You do exactly those same things on stage and people at best are astonished and amazed and bewildered, at worst totally jolted out of the story because you’re suddenly setting up a big puzzle in the middle of the storytelling.

So it’s a constant balance and it’s what I discuss a lot with Matthew Warchus. I always say it’s when you play your aces. Bruce Joel Rubin, an amazing guy who wrote the movie, had basically transferred the movie script so every time Sam walked past something his hand went through it. You could do that. I wanted to but you also wouldn’t want to. If by the time he walked through the door he’s already put his hand through five objects and every person he walks past he walks through, then there’s no impact at that moment. But in a film you wouldn’t play it like that. In theatre you have to be aware that people are seeing it live. It’s working out when things have an emotional impact as well. I don’t think I’m giving too much away to say that the whole set has been designed around these optical effects which are extraordinarily difficult to achieve. In theatre you would never go, “In order to make this guy vanish in a way that’s never been seen before in a show, we’ve got to do everything else backwards from it.” “How long’s that effect going to last?” “Two seconds.”

Pictured below: Richard Fleeshman and Caissie Levy in Ghost the Musical

So you work backwards from when Sam disappears?

There are six or eight moments. The thing which defines Ghost which is very interesting for me as a challenge is that these magic points sit absolutely on key story points. They are not arbitrary. When he learns to go through a door it’s really key to the story. When he can’t pick up an object and learns how to push things, that becomes a fundamental part of the story. If you were doing the radio version you would be left with those points. One of the things that’s funny about the transposition from film to stage is that in a film, because the ghost is invisible to everyone but only audible to the medium, in the film you are constantly seeing Patrick Swayze, and then in the next moment you don’t see him, so you are switching points of view. Famously when he pushes the penny up the door to prove he’s there. What the audiences sees is him pushing the penny up the door and then just for a split second you see Demi Moore’s point of view, the coin floating across the air and then you see it back in his hand. Really what that is about is intention, his face trying to convince her. We set this up in a workshop and realised we could get this coin floating up the door, but it just looked like a magic trick, so we had to come up with a whole other way of delivering that story because it just wasn’t right. We couldn’t switch points of view. There are certain things that play in our favour in the way the story has been constructed but certainly we’ve had to strip a lot of the effects out.

Were you Matthew Warchus’s first call?

I’ve worked with Matthew on many, many shows since 1995 on Volpone at the National, but the bigger thing was Peter Pan at the West Yorkshire Playhouse, which was an epic production. I think they had to run it for two years because it cost so much money. I think I was originally introduced to Matthew by Simon Russell Beale at the National when we were doing Volpone in 1995. He came to me very early on in the process. I remember saying to Matthew on Peter Pan, “Get me in early if you want to do the best stuff.” The really frustrating thing about illusional magic is of course the last thing it is is magic. It’s absolutely the most nitty-gritty technical annoying thing. It’s quite difficult to achieve. It requires a lot of concealment. It suddenly struck me on Ghost that all of a choreographer’s energy goes into what’s on show, and about 95 per cent of my energy goes into concealment. That can be really frustrating, when you’re watching someone who’s totally free to just change that and that. If I want to change something I might have to have someone in a workshop build something for a month. It drives me nuts.

Well, you chose this line of work and I would ask the question why?

Don’t most boys have a fascination with learning magic? Did you?

Not particularly. But I take your point.

Not particularly. But I take your point.

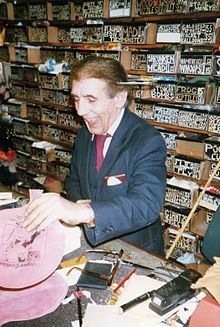

At some point a lot of boys start learning card tricks. I don’t know why it is boys more than girls. There was this joke shop in Southampton Row called Alan Alan’s Magic Spot. Allan Allan (pictured right) used to wear a giant pin through his head. He was actually quite rude. If you asked him if he had anything he always used to say you should look in the window. But if you spent long enough there you actually realised he was a really brilliant guy. He was actually the first man to escape from a straitjacket while hanging upside down from a burning rope. He had this very high-profile career as an escapologist and he was actually very wise and smart, and if you chatted to him for long enough he’d actually give you some really good insights into what you should be doing. “Here’s something that would suit you.” And he would go round the back and come back and show you this card trick. There were a couple of brilliant magic shops in London at that time. Davenport's was still running. It used to be opposite the British Museum so I used to nag my father to take me to the British Museum. It was a bit of a schlep. I grew up in Buckhurst Hill. I’m an Essex boy. I found this trick where if I said I wanted to go to the British Museum he was delighted that I wanted to be educated and then afterwards I’d say, “Oh, can we just go to the magic shop?” And I’d spend three hours in the magic shop.

It was your first trick.

It was. But even at the British Museum the thing that fascinated me was the Egyptian rooms and the mystery. So I was doing tricks. My mum was a childhood actress. She actually gave it up when she got married. My father said she had to choose him or acting. But we were always taken to things like Marcel Marceau. My dad was an artist who went to art school but then went into economics, but he was from an East End Jewish family and I think he wanted to support his parents and realised he couldn’t do it through art. So they were supportive and encouraging on the creative side. And then I did some competitions in my early teens and did magic in the Duke of Edinburgh award and built a box at school for cutting my sister in half. The Sade thing was quite a turning point for me.

Could you tell that story?

I had had some cards printed up, my first business cards, and my mum had been in a pop video with The Kinks, “Don’t Forget to Dance”, and she’d worked with the director Julien Temple and she’d given my cards out, being a good supportive Jewish mother, and they’d got confused and thought she was the magician. They phoned her up asking her whether she could do this tick in the video. She said, “No, it’s my son that does the magic.” So then I got on the phone and was disappointed that they wanted a female magician to double in for the hands and I recommended this other girl, she couldn’t do it and they phoned me back and said, “Any other thoughts?” I said, “My hands are quite small. Maybe I could do it in gloves?” I went to this audition – I was very nervous going to this audition in Soho- and they gave me the job, and on the day they changed their minds about the gloves and, having failed to bleach my even then hairy arms, aged 16, they taped my arms shaved to the elbows and my arms stood in for Sade. I just remember having a real laugh that day.

Watch Paul Kieve's trickery in Sade's 'Your Love is King'

What impact did that have professionally?

I think it helped because Sade would very sweetly talk about it in interviews. She chatted about it on Kid Jensen’s show on Radio 1 at a time when a lot more people listened. She used to phone me up when the video was going to be on TV. I landed an appearance on Blue Peter largely on the back of it when I went in and sliced Janet Ellis into three pieces in my homemade zigzag box.

I left school and was doing my own stage act for a while. I worked in Jersey in variety - it was the end of variety. I was a resident support act in this venue called the Inn on the Park being paid peanuts, but I had the experience of working as a support act for everyone from Chubby Brown and Bernard Manning to Roy Castle and Rolf Harris and the Platter and Gloria Gaynor and Bob Monkhouse. So every night was a different audience. And of course it was surprising how many of them had started in magic. I remember Bob Monkhouse being really really supportive and chatting for hours and getting this amazing time with some of these names. I know he’s incredibly politically incorrect but I remember Bernard Manning being rather charming. The thing that was significant in terms of my theatre work is that I was doing a visual act, it was not chit chat, I was doing an act that was quite highly dense in terms of visual material.

Were you into the chit chat? Derren Brown’s show is partly about his rapport with the audience?

What’s really odd is that when I started I did that entirely. My mum had a pup theatre in the East End, the New Globe Theatre in the Mile End Road and I remember out of complete ignorance, and I’m sure it was terrible; I did a whole show there when I was 16 which was all chat. And then there was a market for a polished 10-minute continental-style act that was all set to music and I rather liked the drama of the mystery. Again, who wants to hear a 17-year-old being a smart arse? And I quite liked the music and the lighting. So at 19, after I’d lost my second assistant, who’d got a better paid dance job in panto, I thought, oh no, I’ve got to train another assistant, so I went into a double act with a local magician called Lawrence Layton. It’s excruciatingly embarrassing but we called ourselves the Zodiac Brothers. We got onto New Faces. But we worked continually. We were identifiable. We did a lot of work on cruise ships.

How long did you do that for?

About four years. I got absolutely fed up with it and wanted to leave and go to university and study something else. I didn't get that far. I got out of the act.

Was it acrimonious?

Was it acrimonious?

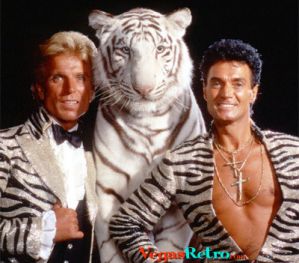

Fairly, although we’re friends now. It was like going through a divorce but the children were the act. We lived out of each other’s pockets. Absolutely everything was invested in this act, including our made-to-measure suits. We worked on a high level. We were doing the QE2. For some reason we wanted to work in Las Vegas. That was the goal in the Eighties. And then I remember going over and seeing Siegfried and Roy (pictured above) and thinking this was a dream to work in Vegas, and when I actually met them I realised this was a bit of a nightmare being in the same show two nights a week. They were on a $50 million a year contract and I remember thinking, God, I wouldn’t want to do that no matter how much someone paid me. I think it was seeing how bored they were – I didn’t meet Roy till years later – but Siegfried was bored out of his brains. And I remember then thinking, I’d like to do this but what I love is coming up with the stuff and creating it. Just having this fear about being a 50-year-old stuck on a cruise ship. We used to see these terrible acts that literally were totally institutionalised. They would go back home for two weeks of the year and they didn’t know what to do because no one had left a chocolate on their pillow at night.

Were you arguing about who owned the tricks?

Oh God, we did at the end.

Did you both ditch the tricks or did you have equal access?

We had one particular act which was successful and had taken us to America, and we’d done the Magic Castle in Hollywood and all that sort of stuff. We bizarrely appeared on Japanese TV. That was the thing that we were most pushing for before we’d decided it was enough. We actually both ended up doing different versions of that act with different people but there wasn’t really a market for it unless you wanted to be on cruise ships all the time. In London in 1991 you might pick up the occasional corporate thing. But there is a link to this. During this period of time, right the way back to the first act I did with an assistant, I auditioned for the Theatre Royal Stratford East variety nights and also we used to try out stuff there as the Zodiac Brothers if we were in town. We always used to get a phone call saying, “Are you free for the variety night?” They were wonderful nights. I was on the QE2, the last contract I did with the Zodiac Brothers, and the day after I got off the ship I got this call from Kate Williams saying, “We’re doing a production of The Invisible Man and we need some help.” I’d already applied for university, I can’t, to be honest, really remember what I’d applied for but it was something in film production. I felt it would be quite interesting going into film.

So you were prepared to abandon magic?

It’s difficult to know. What I knew is that I really wanted to get out of that double act. I didn’t want to be stuck on cruise shops. I could feel my life blood draining away doing three 20-minute acts every two weeks in a bow tie. Probably the material was quite invigorating but it was just clear that we were trying to work in a field that had probably gone 20 years ago.

So you got this call that rescued you from university?

I didn't know at the time who the hell Ken Hill was but he was a protégé of Joan Littlewood. He was an amazing guy. He was a very tall, gruff, blunt man but he absolutely trusted me – I don’t know how or why – just handed over on the effects. I think he knew he could have done something. He was very inventive. He used to have this phrase: “Just jig it out with a bit of ply.” And I think his attitude was probably if I had screwed up royally he’d still have quite a fun show on his hands, the whole idea of doing The Invisible Man (2010 revival pictured below, image © Nobby Clark) being an absurd notion. His team of players who were mostly ex-Joan Littlewood Theatre workshop. The surprising mix which I had no clue about at the time - you have to imagine, I had come in from the world of being obsessed with very high-level Las Vegas magic, wanting to do the most spectacular illusions possible, and then being thrown into this rough, thrown-together, storytelling theatre, and I just went in in complete ignorance with the most full-on magical ways of doing these things.

The tradition of doing magic in theatre at that point was to do it as quickly as possible. Do it in an afternoon, don’t do complicated methods because they are only going to go wrong. We had scenes where the whole blocking had to be arranged around people avoiding this piece of fishing line. He took my stuff and made it work. He used to come in at 7 in the morning at the typewriter and just rewrite a whole scene if he liked the idea. Very, very unprecious about his own writing, because he came from TV. He’d do the same with actors. If an actor was killing a joke he’d just cut it. Working with Ken Hill turned out to be a relationship which lasted till the end of his life, which was in 1995. It was probably the greatest learning I had in theatre. I was really thrown in at the deep end. It was an amazing time to be at Stratford East. I still feel very, very lucky.

The tradition of doing magic in theatre at that point was to do it as quickly as possible. Do it in an afternoon, don’t do complicated methods because they are only going to go wrong. We had scenes where the whole blocking had to be arranged around people avoiding this piece of fishing line. He took my stuff and made it work. He used to come in at 7 in the morning at the typewriter and just rewrite a whole scene if he liked the idea. Very, very unprecious about his own writing, because he came from TV. He’d do the same with actors. If an actor was killing a joke he’d just cut it. Working with Ken Hill turned out to be a relationship which lasted till the end of his life, which was in 1995. It was probably the greatest learning I had in theatre. I was really thrown in at the deep end. It was an amazing time to be at Stratford East. I still feel very, very lucky.

Did that job turn you into an invisible man yourself, in that you withdrew from performance?

The fact is I never totally decided to give up performing and I still haven’t. But I realised that I didn’t need to be doing it all the time.

How often do you perform?

Not very often now but I wrote a book in 1997 which was published around the world and Bloomsbury asked me to do book festivals. I started doing these things and I felt, I’m an author now, I don’t need to do any magic. I can just go out and talk about the history of magic. And of course magic is a wonderful gift for a live thing. So my first version at Cheltenham, there were probably three things I did on the tour. I did a thing at the Polka Theatre at the Wimbledon Festival and it had already expanded at that point. Then I had an opportunity to do it at the Magic Circle Theatre. All this was to do with promoting the book but what it became was a show in its own right. The Southbank Imagination Festival then asked me to do it. By this point my younger brother, Daniel Kieve, who is a pianist and singer, had written some live music for it. So I put him into it. It was actually becoming a show. It really worked for me because I wasn’t having to pretend to be anything. One of the problems I have with doing magic as a stage performance is this peculiar relationship with the audience. I had a growing discomfort with performing magic because it felt like not a very honest thing to be doing. There were things that I was running from in my teens that I wasn’t running away from in my twenties. There is a peculiar balance with that in magic. Either you do the whole thing as comedy, or you do it through a very dramatic stage persona which is, I suppose, what I prefer to do. I’ve never felt very comfortable doing close-up magic. I find it an uncomfortable social thing to do. But I do find a lot of magicians are uncomfortable social beings. But I do think magic is a wonderful thing. It creates its own emotional response which, when you do it well, is wonder or astonishment. You can’t get that with anything else.

Is there such a thing as a typical psychological profile of a magician?

I think it’s the classic thing when you’re young. You learn sometimes quite a simple thing that suddenly impresses adults. You get approval and it gives you a bit of power. That’s something that is an odd thing. I don't feel that at all with the stage stuff. With people I’m working with I don't have to pretend to be doing anything. It is what it is. We’re all working together to hopefully create something that is then wonderful and astonishing for the audience and I don't have to stand there and take any credit for it. I work a lot with Terry King who is a fight director and, in a way, my billing on a show should be magic director. I’m coordinating all of those elements. I love doing it in a collaborative team. Magicians tend to be loners. When I was doing the show, trying to do things without all these fancy lighting rigs, I ended up with a performance which I could take in hand luggage. When I do it I get in through the book. The book is the history of magicians and what tricks they did. So I can go through it more or less as a lecturer. I’m genuinely not taking credit for it. I have to be able to do it well. The zigzag illusion, Harbin’s amazing genius invention which has become a cliché, of the middle of the girl being pulled to one side: this guy built it in his garage and spent 30 years thinking about this thing and built five of them wrong before he got one right. He hit on something which is a work of genius. It’s now become a sort of cliché. I do it in the show and I can say when Harbin did this in 1965 it was on the front page of the papers the next day.

What are the shows which for you represent your top five?

What are the shows which for you represent your top five?

Lord of the Rings (dancing orcs pictured left) was a phenomenal title to work on. I know that it wasn’t welcomed with open arms but when you’re involved in these things from the inside, the last thing, certainly from the point of view of the team in it, was any cynicism about doing that title because of the films. There was this huge challenge of doing this thing which was virtually going to be unstageable as a theatre production. I agree with Matthew that you can do anything on stage if you approach it in the right way. Whether or not Lord of the Rings artistically was a success or not is not for me to say. But in terms of the scale of it and the evolution of that piece it was an amazing one to work on. I got to do one thing which I was very proud of which was the vanishing of Bilbo Baggins at the beginning, because we managed to do something that hadn’t been done before. I did have the benefit of it being very early on in the show. Every single thing that changes in where it happens in the story affects what I can do. The fact that Bilbo disappears at the beginning meant that I could do something I couldn’t do in Ghost at all. You can do something at the beginning of the show that requires a half-hour pre-set, incredible precision in terms of where things are placed. I remember Derren Brown came to see it and he was totally fooled by it. You welcome these things. I know that they’ve got to look remarkable because that’s what my job is, but that’s just my job. You just get on with your work so you can almost forget that it has a memorable impact on the audience. And that’s what magic can do.

I’ve worked on over 100 shows. What’s really memorable is a couple of shows with Improbable. Cinderella was really interesting, working with their improvised style. Years later we did Theatre of Blood which for me was fantastic. It was using stage illusion in order to deliver a series of very extreme murders. The magic was very central because the high dramatic point in each of the scenes was always the murders. You had to deliver something special.

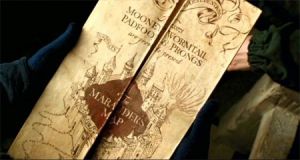

What was your task on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban?

The direct of the third film, Alfonso Cuarón, wanted specifically to have some things in the film that weren’t computer effects. He wanted someone who worked with directors and he wanted there to be supplementary effects and illusions that occurred in real time in shot. It was mainly to do things that were background or perhaps wouldn’t make their way in if they were CGI or special effect. He wanted a bit more control. So I did this thing that Americans called a Show and Tell. So I went in on a February morning and all the departments were there and producers. It wasn’t auditioning for me. It felt like I was auditioning for live magic. I had two hours to show all the range that you could do in live magic and that included big scale things down to the smaller things appearing in the hands. One of the things I demonstrated was a note that folded up by itself. The production designer immediately came over and said, “We’ve got this thing called the Marauder’s Map (pictured below). It has to fold up by itself. We’d love you to look at that.” Also I got a sense that it’s such a huge film that you get a division between departments. Design can come up with something and by the time it goes through CGI it’s not really what they wanted it to look like. There was one effect I suggested, which I used to do in my old stage act: a candle that multiplies in the fingers. I said, “If you’ve got a wizard in a pub, he can be reading by candlelight and what you would do is make candles appear in his fingers.” If you take an old jaded trick – a nice effect – you put it into a context, and suddenly there’s a justification for it.

How will people know that it’s live magic?

How will people know that it’s live magic?

In that example, the director said, “How long would it take to teach an actor?” I said, “Oh, a few days.” “Why don't you do it?” I’m the only magician ever to have appeared in the Harry Potter films and that is the only thing done by sleight of hand.

But most people won’t know it was real magic.

In the end it doesn’t matter. For me it was a wonderful opportunity to work on that film set and I had a wonderful time. But for the director it was a way of getting a few more visuals in that wouldn’t have been there. I did the floating balls in the astronomy room. My position on it I always felt was tricky. They’ve got this huge special effects team and CGI and I’m coming in and saying, “I can do that with a bit of thread.” You can imagine that doesn’t always go down well. The thing I’m proudest of in that film is that I get the final special effect, which is the Marauder’s Map folding up by itself. I made that map on the table in my old house in Hackney and I made it as a one-person thing because I had to go in and show the producers. I made this thing that didn’t require 10 people to operate it and it did the job. Because it wasn’t done on machines I could give it little bits of personality. Essentially I was puppeteering it. When I was working on the film I realised that’s the difference between what I was doing and the brilliant special effects department. Everything I did was operated at some point by a person. It was performed, like puppetry.

What did the CGI guys say to you?

They didn’t say anything to me.

They tried to make you the invisible man.

I just think it’s different worlds. I think they thought I was a freak, a lunatic. My stuff is always very, very exposed. If I fail, everyone sees it. I can’t build my stuff in a model box and I can’t do an animation of it. It’s exciting because if it works, it’s fantastic. If this heightened moment doesn’t work, then it’s excruciating. I’m also a one-person department. On Harry Potter CGI make all their mistakes in private. If you’re doing a computer animation that doesn’t work, you don't show anyone. My experience as a performer is helpful like that. You are flying by the seat of your pants.

Watch the theatrical trailer for Ghost the Musical

Explore topics

Share this article

more Theatre

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Add comment