Rambert, Cardoon Club/ Roses/ Monolith, Sadler’s Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Rambert, Cardoon Club/ Roses/ Monolith, Sadler’s Wells

Rambert, Cardoon Club/ Roses/ Monolith, Sadler’s Wells

One of Paul Taylor's greatest works, immaculately performed

Paul Taylor's Roses is called Roses because, well, because it is. There are no roses here, no flowery sentiment, no overwrought angst and emotion. This, one of Taylor’s most beautifully serene works, is the smell of roses on a still May evening: fleeting, evanescent and heart-breakingly beautiful. It is also some of the most magisterial - and startlingly original - choreography, even a quarter of a century after it was first made.

The curtain rises on five couples, the women formally dressed in long navy dresses, the men, in contrast, in informal grey/brown undershirts and trousers. To Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll, each moves forward, returns, blends with the group. The Siegfried Idyll, with its beautiful singing line, is a surprisingly good fit for dance, and Taylor explores its depths as the couples explore through movement the idea of coupledom, of romantic love not as seen on TV, but as lived by adults. Graciousness, decorum, gravitas, gentleness with themselves and each other are the prevalent emotions.

The movement is one that echoes this graciousness, centring as it does on an initial round, when the dancers stand in a circle, hands extended to their neighbours’ shoulders. They flow out of this into a Greek frieze of sorrow and pity at the rear as, one by one, each couple moves forward to perform, always linked to what went before, what comes after, yet each couple always with their own leitmotif.

Some movements repeat and return – the women leaning in towards their partners, a cantilevered gesture of faith and reliance, or a woman reaching down to her seated partners to briefly, softly, cup the crown of his head with her hand in a fleeting moment of infinite tenderness. And then, just as you think, Taylor is really the classical king of contemporary dance, one of the women somersaults the length of her partners supine body, or a man cartwheels through his partner’s split-leg handstand.  In the final movement, to Heinrich Baermann’s Adagio for Clarinet and Strings (previously attributed to Wagner too, and a wonderful performance from solo clarinet Ian Scott), a couple in white appear: perhaps the ideal, what all couples would be, if they could. It doesn’t matter, ultimately, what or why – the being is so beautiful, it is hard to leave it behind.

In the final movement, to Heinrich Baermann’s Adagio for Clarinet and Strings (previously attributed to Wagner too, and a wonderful performance from solo clarinet Ian Scott), a couple in white appear: perhaps the ideal, what all couples would be, if they could. It doesn’t matter, ultimately, what or why – the being is so beautiful, it is hard to leave it behind.

Unusually, no couple enters or exits in this brief but transcendent piece. Tim Rushton’s Monolith (pictured right, photo Chris Nash), by contrast, is a series of ferocious entries and exits. Rushton, from the Midlands originally and trained at the Royal Ballet School, has been at the helm of Danish Dance Theatre for 10 years, and it is only in the last few years that a few bits and pieces of his work have begun to be seen in British theatres.

His Royal Ballet School training, combined with an entirely European career, has given him an interestingly complex dance language, taking the expressionistic force from north Europe, and combining it with the sleek, fleet fluidity of classical ballet.

Monolith is set in some earlier, prehistoric time, with a beautiful set of bronze pillars, bronze burnished light (beautifully realised by Malcolm Glanville and Rushton), and a gesture towards some silvery low-lying landscape. The dancers, too, are bronzed, in bronze singlets and shorts for the men, and rather unfortunate strapless bathing suits for the women (designed, together with the sets, by Rushton and Charlotte Østergaard, they closely resemble the outfits Wilma used to wear in The Flintstones). But this is the single duff note. The plangent musical language of Pěteris Vasks drives the dancers in groups of threes and in couples on and off, creating a sense of urgency, of a people’s desire for purpose and meaning in their life. The choreography matches this focus, with a ferocity that sits nicely at odds with the beautiful bronzed light: this is more complicated than it seems, it is telling us, and Monolith will repay repeated viewings.

The choreography matches this focus, with a ferocity that sits nicely at odds with the beautiful bronzed light: this is more complicated than it seems, it is telling us, and Monolith will repay repeated viewings.

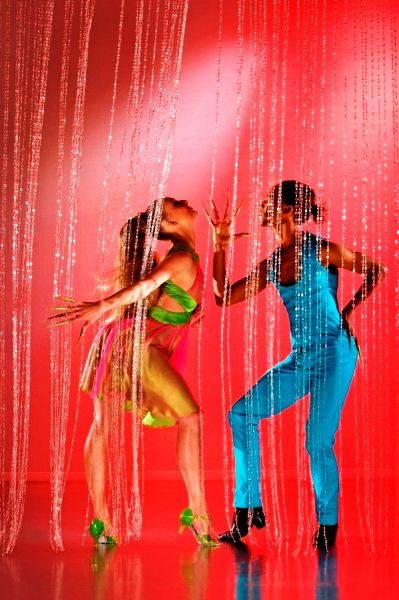

The Cardoon Club (pictured left, photo Eric Richmond), sadly, does not repay one viewing. It is 10 minutes of content, stretched out into nearly three quarters of an hour of turgid posing and prancing. The design, by Michael Howells, is kitschy fun, but while fun’s fun, a girl can’t laugh for 45 minutes straight with nothing happening on stage. The 10 minutes or so of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s "Swamp Gas" propels choreographer Henrietta Horn, finally, into letting her dancers rip, but otherwise the annoying tickety-tack of the Hammond-orchestra/easy-listening score by Benjamin Pope is a paean to banality.

Share this article

more Dance

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Add comment