Jan Gossaert’s Renaissance, National Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Jan Gossaert’s Renaissance, National Gallery

Jan Gossaert’s Renaissance, National Gallery

A model exhibition, of a neglected master

Jan, or Janin? Gossart, or Gossaert? Or Mabuse? After a mere five centuries, we haven’t settled on a name quite yet (even for this exhibition: at the Metropolitan Museum, the same show spelt it “Gossart”). We don’t know where he was born, although Maubeuge, then in Hainault, now in France, is the best guess, hence “Mabuse”. His birth date too is a mystery: the Grove Dictionary of Art suggests 1478, while the National Gallery just shrugs and gives us “active 1503”. What is in no doubt, however, in this very model of an exhibition, is that Jan Gossaert represented not merely one of the peaks of northern Renaissance art, but that, in a constantly surprising career, he also synthesised great swathes of the Italian art world, both classical and Renaissance, creating something new and hugely potent.

The earliest appearance of Gossaert in the records was when he joined the retinue of Philip of Burgundy, travelling south with his new patron to Rome in 1508. From the start, Gossaert’s studies after the antique show a sharp development from the norms of northern Gothic, while his characteristic fondness for architectural settings and complexity of composition and perspective can already be seen. (Sheet with Studies after Antique Sculpture, pictured right, Leiden University Library)

The earliest appearance of Gossaert in the records was when he joined the retinue of Philip of Burgundy, travelling south with his new patron to Rome in 1508. From the start, Gossaert’s studies after the antique show a sharp development from the norms of northern Gothic, while his characteristic fondness for architectural settings and complexity of composition and perspective can already be seen. (Sheet with Studies after Antique Sculpture, pictured right, Leiden University Library)

His Adoration of the Kings (main picture, above), one of the great treasures of the National Gallery, is northern in its attention to detail, surface and jewel-like colour, but the astonishingly grand, sculptural figure of the Madonna that centres the picture, as well as the architectural depth and perspective show how profoundly Italy had inflected Gossaert’s eye. New, too, is his psychological exploration. The kneeling king stares at the Christ Child in awe, but also in amazement and a certain amount of doubt. This is what faith is, Gossaert seems to be saying: that one doubts, and yet worships none the less.

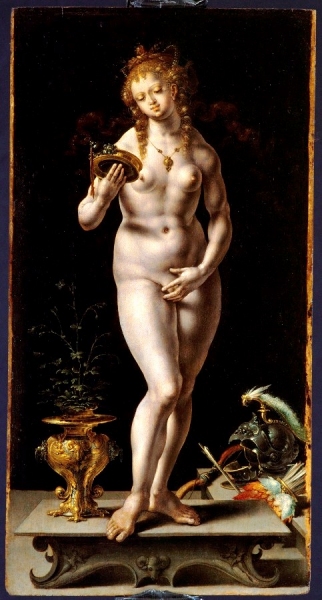

It is hard to imagine any other artist producing the vast Adam and Eve on show here. Adam has very obviously eaten from the tree of knowledge, even though Eve still holds the apple: he gestures to his mouth, lasciviously open, and his other hand plucks at Eve’s fleshy arm, grasping for more. Yet while the grandeur and eroticism of the figures say ‘Rome’, the models, as are shown in nearby examples, are influenced by the work of Dürer in the north. Similarly, a Venus (pictured left, from the Pinacoteca dell'Accademia dei concordi e del seminario vescovile, Rovigo) from around 1521 also merges influences in a work of great singularity. The sculptural quality of the flesh, given a marble-like sheen, draws on Gossaert’s interest in classical art, while the almost trompe-l’oeil perspective of the right knee jutting into the viewer’s space, together with the still-life elements at the bottom of the image – a vase of gillyflowers, and Mars’ helmet, bow and quiver – are all rendered in precise, northerly van Eyckian detail. Each element of Gossaert’s art is comprehensible; combined, they make for a hallucinatory experience.

Similarly, a Venus (pictured left, from the Pinacoteca dell'Accademia dei concordi e del seminario vescovile, Rovigo) from around 1521 also merges influences in a work of great singularity. The sculptural quality of the flesh, given a marble-like sheen, draws on Gossaert’s interest in classical art, while the almost trompe-l’oeil perspective of the right knee jutting into the viewer’s space, together with the still-life elements at the bottom of the image – a vase of gillyflowers, and Mars’ helmet, bow and quiver – are all rendered in precise, northerly van Eyckian detail. Each element of Gossaert’s art is comprehensible; combined, they make for a hallucinatory experience.

It is perhaps in his secular portraiture that Gossaert becomes most obviously a northern painter. The Portrait of a Man (Jan Jacobsz Snoeck?) (pictured below, National Gallery of Art, Washington) shows a northern government official surrounded by the tools of his trade – paper, files, scales, inkwell – looking up from his account books to cock his head quizzically at the viewer. Here the northern love of still-life detail is given full rein in Gossaert’s almost fetish-like depiction of the light’s different sheens over the different metals, or the way paper folds and curls and tears: each object has as much individuality as his sitters.  Even the seemingly straightforward compositions are thrillingly achieved. The Portrait of Henry III of Nassau-Breda puts the sitter in front of a trompe-l’oeil frame, his hat tipping out of one architectural space and into another, before the panel was itself set in another frame. And in a seemingly simple single-panel image of the Virgin and Child (1520), the blue gown of the virgin blends into the black background, while her blonde, Leonardo-soft sfumato hair is anchored back into the arched shape of the frame by the echo of her white headdress. Black, blue, white – so simple, and yet with these few shades Gossaert builds an entire architectural reality.

Even the seemingly straightforward compositions are thrillingly achieved. The Portrait of Henry III of Nassau-Breda puts the sitter in front of a trompe-l’oeil frame, his hat tipping out of one architectural space and into another, before the panel was itself set in another frame. And in a seemingly simple single-panel image of the Virgin and Child (1520), the blue gown of the virgin blends into the black background, while her blonde, Leonardo-soft sfumato hair is anchored back into the arched shape of the frame by the echo of her white headdress. Black, blue, white – so simple, and yet with these few shades Gossaert builds an entire architectural reality.

To art historians, Gossaert is famous for bringing the Latin Renaissance to the north; to the general public he is not much known at all. Yet his work is a thrilling fusion of styles, creating a pan-European world of, if you will, gothic classicism, a northern love of detail and psychological seen through the rigour and proportion of the classical world.

This is exactly the kind of show our national, as well as National, Gallery should be showing. Intelligently displayed, carefully curated, it sure-footedly explores the complexity of European art at the beginning of the sixteenth century. A blockbuster of artistic integrity.

- Jan Gossaert's Renaissance at the National Gallery from 23 February until 30 May

- Read curator Susan Foister on Jan Gossaert in History Today

- Jan Gossaert's Renaissance has been supported by the Flemish Government

Find Maryan W Ainsworth, ed, Man, Myth and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossaert's Renaissance on Amazon

Find Maryan W Ainsworth, ed, Man, Myth and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossaert's Renaissance on Amazon

more Visual arts

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Add comment