Connolly, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bělohlávek, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Connolly, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bělohlávek, Barbican

Connolly, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bělohlávek, Barbican

Poise and dignity in Wagner, Lieberson and Dvořák

As experienced Wagnerian Jiří Bělohlávek came on to launch the BBCSO's new season in mid-air with the Tristan Prelude, I wondered whether the world's finest interpreter of Isolde's serving maid Brangäne, lustrous mezzo Sarah Connolly, was waiting to up her game, and her range, and tackle the Liebestod. Sadly not: that remained, as often in concert, Music Minus One. Connolly was there for a different kind of game-upping - a noble attempt to enter the charmed circle that's developed around the memory of the great Lorraine Hunt Lieberson with husband Peter Lieberson's Neruda Songs.

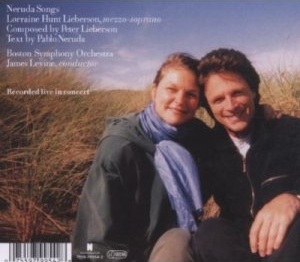

Hunt Lieberson died from cancer in July 2006 at the age of 52, having recorded the five songs just over seven months earlier (the Liebersons together on the back sleeve of the recording pictured right). The words of Neruda's "My love, if I die and you don't" still carry an unbearable poignancy, especially given the uniquely communicative, vibrant tones which set the mezzo among the greatest singers of all time. Did Connolly's performance detach us from thinking too much about those circumstances and encourage us to accept it for itself? Up to a point.

Hunt Lieberson died from cancer in July 2006 at the age of 52, having recorded the five songs just over seven months earlier (the Liebersons together on the back sleeve of the recording pictured right). The words of Neruda's "My love, if I die and you don't" still carry an unbearable poignancy, especially given the uniquely communicative, vibrant tones which set the mezzo among the greatest singers of all time. Did Connolly's performance detach us from thinking too much about those circumstances and encourage us to accept it for itself? Up to a point.

Connolly has different qualities: the most centred, velvety mezzo instrument in the business, allied to a quiet dignity which you sometimes feel keeps something in check. She can let loose, as anyone who heard her ripping into Britten's Phaedra with this orchestra under Edward Gardner several seasons back will never forget: that was a performance up there with Dame Janet Baker's and Hunt Lieberson's. But a certain detachment was appropriate here, and despite the giddying Latin lunges of key phrases in the earlier songs, Connolly's version of Lieberson's Neruda kept its Mona Lisa smile.

When all's said and done, the Chilean poet's sonnets are great, while the music is just very good. Bělohlávek held the ear with equally dignified, supple orchestral colours - outstanding contributions from the flecks of Sioned Williams's harp and Richard Simpson inflecting the little oboe figures which give the third song of imagined separation its special kick. Lieberson is unusually restrained among contemporary composers, never resorting to the wash of all-purpose percussion (only maracas beat a haunting bossa nova rhythm, complete with memorable four-note woodwind tag, in the dream-dance of "And now you're mine"). But ultimately it would need a Mahler to do justice to the infinite wisdom of the farewell, and here simplicity is not quite enough.

Wagner's Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde are always going to be a hard act to follow, and in previous seasons, the BBC Symphony Orchestra has had different solutions, following the Prelude in one case with the complete opera over three different concerts under Donald Runnicles, and in another allowing David Robertson to glide without a break from its last pizzicato into the nightmare world of Schoenberg's Erwartung. Bělohlávek (pictured below at this year's Proms by Chris Christodoulou), who conducted the first run of Tristans at Glyndebourne, had his own slow-burn assurance, warming the now-resplendent BBCSO cellos once their song of infinite yearning finally got under way, if not bending much thereafter (it didn't help that I had a Wagner nut in front of me, deciding how it should go and shaking his head vigorously when Bělohlávek didn't do what he or I wanted).

The Liebestod was sumptuous in sound but stiffer in movement - and can we ever hear it without the rapturous tones of soprano swimming in the soup? I bet you that if Petra Lang can get up there, Connolly could have done, too. Never mind: she had her work for the evening cut out.

Most idiomatic sound of the evening came in Bělohlávek's Czech stamping ground, Dvořák's inflamed Seventh Symphony. Let me confess that I have almost as much of a problem with this work as my colleague Igor Toronyi-Lalic does with Shostakovich Five. In short, I just don't believe the high, semi-tragic attitude that Dvořák seemed to be striking for a British premiere, in much the same way that Tchaikovsky bowed to Germanic convention in his Fifth. Until Dvořák reaches his ultimate masterpiece, the opera Rusalka, the lofty gestures always ring a little hollow to me. I'm more comfortable with the native wood-notes that sound more consistently throughout the Sixth and Eighth Symphonies.

Most idiomatic sound of the evening came in Bělohlávek's Czech stamping ground, Dvořák's inflamed Seventh Symphony. Let me confess that I have almost as much of a problem with this work as my colleague Igor Toronyi-Lalic does with Shostakovich Five. In short, I just don't believe the high, semi-tragic attitude that Dvořák seemed to be striking for a British premiere, in much the same way that Tchaikovsky bowed to Germanic convention in his Fifth. Until Dvořák reaches his ultimate masterpiece, the opera Rusalka, the lofty gestures always ring a little hollow to me. I'm more comfortable with the native wood-notes that sound more consistently throughout the Sixth and Eighth Symphonies.

That said, there are still quite a few of those here, and Bělohlávek had the measure of the big outbursts, focusing the sound and offering flexibility without lachrymose sentimentality. The Scherzo especially was a lesson in effortlessly bouncing dance-inflection. The evermore characterful BBCSO woodwind, led here by Richard Hosford's warm clarinet, softened the harsh edges the orchestra can take on in the Barbican - maybe they've been having to project too hard into the Albert Hall for too long - and the cellos once again came to the lyrical forefront in the loveliest variation of the slow movement. A searingly original, unpredictable symphonic experience like the Sibelius Lemminkäinen of the previous evening or Bělohlávek's overwhelmingly wonderful Martinů series last season it wasn't, but it seemed to make an enthusiastic audience very happy indeed.

Watch Sarah Connolly at the 2009 Last Night of the Proms perform the last of Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen:

Share this article

more Classical music

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Add comment