Irving Penn: Small Trades, Hamiltons Gallery/ Portraits, NPG | reviews, news & interviews

Irving Penn: Small Trades, Hamiltons Gallery/ Portraits, NPG

Irving Penn: Small Trades, Hamiltons Gallery/ Portraits, NPG

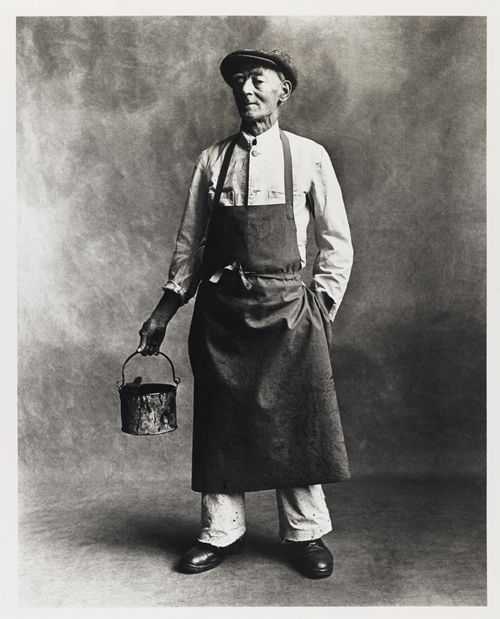

Penn photographed tradesman with as much care as he portrayed celebrities

Similarly black and white, they were created with the time-consuming and expensive early 20th-century platinum palladium process which is responsible for the small editions (from three to only 30-something), for their high prices (£75,000 to £250,000) - and for their unusual beauty.

Part of the fascination with these workmens’ portraits lies with the stories of models posing with heads high, and exuding pride in jobs which no longer exist. Penn told Tim Jefferies, director of Hamiltons gallery and curator of over 20 Penn exhibitions, that he squeezed the sessions in between fashion shoots and celebrity portraits, often in studios littered with couture dresses. It was, he said, “like some crazy circus”.

My enthusiasm for the street traders in no way detracts from the quality and perfection of Penn’s celebrity portraits, but each collection represents interestingly different approaches to portraiture. For the silver gelatine celebrity prints currently on show at the National Portrait Gallery, he moulded patches of stark blackness into shapes created by Dietrich’s coat, Hitchcock’s bulky suit, even Al Pacino’s quiffed hair. And his complex compositions indulged an obsession with triangulation and mathematical configurations which include the signature corners where he corralled his world-famous subjects into creating their own fascinating poses.

With the tradesmen, he took a simple approach, posing them standing with their tools, against a neutral backdrop. It’s interesting to notice their reactions to the camera: celebrities of course, inhabit view-finders and plan and manage their image, but these 1950s workers almost certainly won’t have seen the inside of a Vogue magazine photographer’s studio and had to make it up. Invited by Penn’s scouts, they were paid a few francs, pounds and dollars to pose. Only the Americans disobeyed the brief to wear work clothes; they arrived in their Sunday best and were sent home to change.

The photographer imposed a "look" suggesting how they had grown into their work roles. Heads are slightly tilted and the slightly downcast eyes lending an air of proud superiority. Penn seems to have photographed them from slightly low to enhance that effect. I sensed they carried with them the smells from the streets where they worked amongst traffic, trains, machinery and hordes of people, and the slightly grubby tonal ranges and textures of the prints collude in creating that effect. (Right below: House Painter, London, 1950 ©The Irving Penn Foundation)

Le Chevrier perfectly epitomises these qualities: with his Charles Aznavour features and bemused half-smile, the cheese-man holds his box as proudly as an artist with his paints. In complete contrast, London’s jolly Chamois Seller is enveloped in a patchwork of wash-leathers like the Green Man of English folklore whose outfit is made of leaves. Emerging from under his leathers is a pair of shiny shoes. In New York, the tall, besuited News Dealer (New York, 1951), holds a bundle of papers under one arm and in a Noel Coward-like gesture, a lit cigarette in a holder in the other hand. Close scrutiny reveals a small pile of ash on the studio floor.

Le Chevrier perfectly epitomises these qualities: with his Charles Aznavour features and bemused half-smile, the cheese-man holds his box as proudly as an artist with his paints. In complete contrast, London’s jolly Chamois Seller is enveloped in a patchwork of wash-leathers like the Green Man of English folklore whose outfit is made of leaves. Emerging from under his leathers is a pair of shiny shoes. In New York, the tall, besuited News Dealer (New York, 1951), holds a bundle of papers under one arm and in a Noel Coward-like gesture, a lit cigarette in a holder in the other hand. Close scrutiny reveals a small pile of ash on the studio floor.

Close observation also pays off with the Chimney Sweep (£150,000), a man immortalised in three different poses involving the positioning of his brush. This is a masterpiece of Irving Penn design, drawing on the brushes’ sculptural potential: fully opened, it resembles a wheel and is beautifully, blackly, silhouetted against the backdrop. But the veiny hands and similarly hard-worked holey trousers are reminders of how easy it is to romanticise such lives.

Navy Navvy (London, 1950) is the most obviously hard-pressed subject, with the implications of his workman’s shovel, stained and torn clothes and worn-out face. But the carefully tied neckerchief adds an important and dashing individuality, and there is no suggestion that the Vogue fashion photographer interfered with his wardrobe. But what about the elegantly turned-up collars and shiny shoes, the hands fixed in sophisticated shapes - a little irresistible styling perhaps? I imagine that he left his subjects to settle into their own depiction of themselves, in their unselfconscious 15-minutes of fame, two decades before Warhol launched collective narcissism on us. Whichever way, the results are bewitching.

- Small Trades, Irving Penn continues until 24 April at Hamiltons Gallery, 13 Carlos Place, London W1

- Find Small Trades on Amazon.

- Irving Penn: Portraits continues until 6 June at the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin's Place, London WC2

- Irving Penn's website.

Share this article

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment