Reissue CDs Weekly: BBC Radiophonic Workshop | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Reissue CDs Weekly: BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Pioneering work from the creators of Doctor Who’s sounds and an exclusive interview with the Workshop’s Mark Ayres

BBC Radiophonic Workshop: BBC Radiophonic Music / The Radiophonic Workshop

BBC Radiophonic Workshop: BBC Radiophonic Music / The Radiophonic Workshop

The inescapable 50th anniversary of the television debut of Doctor Who has had the side effect of drawing attention to the work of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, the backroom outfit who created the otherworldly theme, sound effects and atmospheric colour for the series. Of course, Doctor Who was just one BBC production they worked on. The corporation allowed the Workshop to close 15 years ago, in 1998 – a not-so happy anniversary. It had been established in 1958.

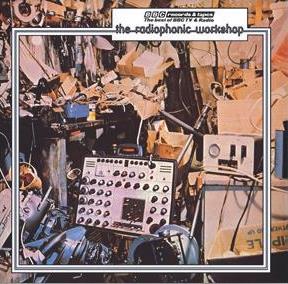

When the Radiophonic Workshop’s paymasters were feeling more favourable to their band of sonic innovators, they issued albums by them on the BBC imprint. BBC Radiophonic Music was originally issued in 1971, and The Radiophonic Workshop in 1975. The latter was a commercial release but the former – known colloquially as The Pink Album due to its sleeve – was only distributed to television producers and directors. Both are rare and sought after. These smart, vinyl reissues are long overdue. There have been compilations of Radiophonic material, but this is how the music and sounds were heard when the Workshop was still functioning – each album is a form of audio verité.

With music created to accompany visuals, the core concern has to be whether it can actually be listened to when divorced from what it was synchronised with. In this case, with many of the resulting creations bearing only a passing resemblance to music, can it be more than a curiosity? Can it slot into experimental traditions, including concrête?

Certainly, with John Baker using a cork pulled from a bottle and metal springs to create “New Worlds” and “Radio Nottingham”. David Cain worked with tape manipulation. Delia Derbyshire employed electronic sources and used tape. The commercial availability of synthesisers meant the Workshop’s staff didn’t have to work from scratch with their effects, noise generators and oscillators. The job became easier. Paddy Kingsland blended electronic and conventional instruments. After the material on these albums was recorded, digital technology arrived.

Certainly, with John Baker using a cork pulled from a bottle and metal springs to create “New Worlds” and “Radio Nottingham”. David Cain worked with tape manipulation. Delia Derbyshire employed electronic sources and used tape. The commercial availability of synthesisers meant the Workshop’s staff didn’t have to work from scratch with their effects, noise generators and oscillators. The job became easier. Paddy Kingsland blended electronic and conventional instruments. After the material on these albums was recorded, digital technology arrived.

At the time of these albums, this was still a make-and-do world which brings an edge to all that’s heard here. Also, it was not a world which sanctioned experimentation for its own sake. The end product had to be coherent, fit the brief and be made within the budget. There were deadlines. Some of the characters working at the Radiophonic Workshop may have been eccentric and others may have left to pursue their own – more open-ended – ventures but these albums are an extraordinary record of a creativity which was (then) unsung.

As to the core question – can it be more than a curiosity? Absolutely. The music and sounds heard here are atmospheric, frightening, joyful, playful and startling. There are tunes. They can be hummed. And the theme from Doctor Who does not appear. Most of all though, whatever their history or source, these are fantastic albums.

Overleaf: the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Mark Ayres discusses its legacy

Mark Ayres is the Radiophonic Workshop’s archivist, As well as being behind reissues of their material, he performs with them live. Although he was not a Workshop employee, he knew all the staff from his teenage years, hung around the Workshop itself and would work on Doctor Who in the late Eighties. When the Workshop closed, he spent 18 months rescuing and cataloguing the equipment and tapes. More than an honorary member of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, he has kept it alive. He spoke exclusively to theartsdesk. (pictured right, Mark Ayres on stage with the Radiophonic Workshop)

Mark Ayres is the Radiophonic Workshop’s archivist, As well as being behind reissues of their material, he performs with them live. Although he was not a Workshop employee, he knew all the staff from his teenage years, hung around the Workshop itself and would work on Doctor Who in the late Eighties. When the Workshop closed, he spent 18 months rescuing and cataloguing the equipment and tapes. More than an honorary member of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, he has kept it alive. He spoke exclusively to theartsdesk. (pictured right, Mark Ayres on stage with the Radiophonic Workshop)

“I was brought up in the Sixties. The sound of the Radiophonic Workshop was the sound of my childhood. I studied piano and flute, took radios to bits and played with tape recorders. I did go the first Doctor Who convention and met the Workshop's Dick Mills. At age 16, I persuaded him to show me around the Workshop. I came out of university with a degree in electronics and music. Occasionally, I would haunt the Radiophonic Workshop, although I worked for TVAM. In 1987, we all got the sack from TVAM and I then worked on Doctor Who incidental music for two years.

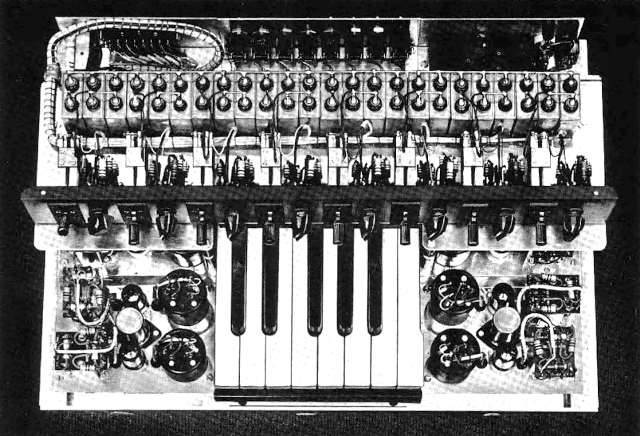

It was inevitable the Workshop would close. John Birt had come in as Director General and started the Producer Choice policy, to get producers to concentrate on what productions were costing. The Radiophonic Workshop had to put a price on their services – they had pensions, a canteen, night guards, this, that. It was cheaper for producers to go to a freelancer. If a producer could get the same service outside the BBC for less, they could go outside. It was money leaving the BBC. In order to survive, the Workshop had to become a music factory rather than an experimental music laboratory. A lot of people in the BBC were slightly embarrassed that departments were closing. Programme makers certainly were. (pictured left, part of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's sonic arsenal)

It was inevitable the Workshop would close. John Birt had come in as Director General and started the Producer Choice policy, to get producers to concentrate on what productions were costing. The Radiophonic Workshop had to put a price on their services – they had pensions, a canteen, night guards, this, that. It was cheaper for producers to go to a freelancer. If a producer could get the same service outside the BBC for less, they could go outside. It was money leaving the BBC. In order to survive, the Workshop had to become a music factory rather than an experimental music laboratory. A lot of people in the BBC were slightly embarrassed that departments were closing. Programme makers certainly were. (pictured left, part of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's sonic arsenal)

But the Workshop never formally closed – it just slowly ceased to be. After it was gone, there was still a room with sign saying Radiophonic Workshop on the door and a technician inside doing noise reduction. It stopped doing creative work in 1996.

Did I think there would be afterlife? Not at all. In 2001 I was approached by the artists Rory Hamilton and Jon Rogers to make a soundtrack to a work called Generic Sci-Fi Quarry. We literally took over a quarry with an enormous surround sound system, that's when we realised the Workshop still had life. There are so many people now in music where the Radiophonic Workshop is in the blood – Orbital, The Aphex Twin. It's also a subtle influence for George Martin and The Beatles, and Pink Floyd. It was a part of many things going on in the Sixties which would result in something like The Dark Side of the Moon.

It also has a kind of mystique about it as it was part of corporate organisation. It was not a load of hippies locking themselves away for six months and coming up with Sgt. Pepper. There was an indelible, almost invisible, imprint left. You see that with Mark Gatiss, especially this week with An Adventure in Space and Time.

Today, the BBC are very happy with what we are doing. It’s win-win all round. It’s a BBC brand to be used, and we get to have fun with the archive. With what we do now and live, we’re lucky; we have 50 years of technology with us – from tape to the digital. We want to explore the history of the Radiophonic Workshop and, next, create new music.”

Explore topics

Share this article

more New music

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Add comment