Flatshare with Bowie: what happened next | reviews, news & interviews

Flatshare with Bowie: what happened next

Flatshare with Bowie: what happened next

David Bowie's flatmate recalls the heady days of the Beckenham Arts Lab and a recent reunion

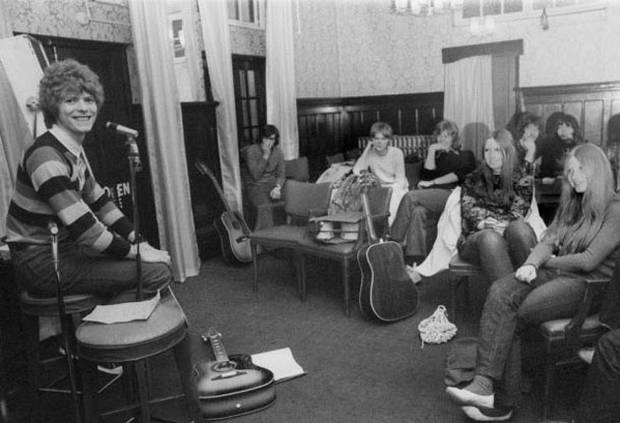

Forty four years ago David Bowie was living in the spare room of the suburban flat I shared with my two young children. He was broke and I was only occasionally employed – so we started a Sunday night folk club in the Three Tuns pub in Beckenham High Street – for fun and so he could pay me some rent.

On the first night we transformed the dingy back room of a very average pub into a psychedelic dream machine. I operated a primitive light projector using glass slides and inks that cast multi-coloured abstract blobs and splatters onto bed sheets hung on the walls. We replaced cold fluorescent lighting with candles on the tables, we perfumed the air with incense and covered the remaining wall space with Californian posters. That first evening was headlined by Tim Hollier – one of David's friends from the London folk scene. David performed and compered and 20 people paid £2 each to come in. We covered our costs.

Our free festival was probably the first of its kind in the UK and has achieved legendary status

The following Sunday David's artist friend George Underwood designed our advert – a considerable improvement on our effort the previous week. Keith Christmas was our headline act, Tony Visconti came to play bass and, in true folk club tradition, several other musicians turned up to jam. A local avant garde ensemble called Comus drifted in and offered to play every week for free. My 10-year-old daughter played the stylophone for "Space Oddity". We had 50 paying customers and made a small profit.

From week three onwards the back room was packed to capacity. We had tuned into the zeitgeist – taking central London hip culture into the southern suburbs, where the youth of the time was just beginning to experiment with marijuana and LSD. David had been a professional musician for years and knew how to put on a good show. He was not famous, but he was known and appreciated by folk-rock cognocenti.

As the music business jungle drums broadcast the news that David was attracting a following on his home patch, established performers were happy to take a 20-minute train ride from Victoria to join in the fun. There was the American folkie Amory Kane for example, Peter Frampton, Dave Cousins and his band The Strawbs and even Lionel Bart.

Meanwhile in London, the Drury Lane Arts Lab was in its heyday. I had hung out there once or twice and so had David. I cannot remember exactly how it came up in conversation, but we decided to ask our Sunday devotees if they would like to transform the Folk Club into an Arts Lab. We hit the bullseye again. Our mainly young audience gave us an enthusiastic thumbs, up so the Folk Club became the Beckenham Arts Lab – joining the burgeoning Arts Lab movement across England from Manchester to Southampton.

We called ours Growth – which signposted a radical agenda incorporating artistic expression, social activism and the hippie ideals of love, peace and freedom. It was the polar opposite of what the word represents nowadays.

We called ours Growth – which signposted a radical agenda incorporating artistic expression, social activism and the hippie ideals of love, peace and freedom. It was the polar opposite of what the word represents nowadays.

Growth burst into life instantaneously. The Sunday gatherings expanded into a conservatory and eventually the pub garden. People brought their paintings, poetry, stories and crafts. We produced a weekly newsletter. We rehearsed street theatre in the park and performed it along the High Street on Saturday mornings. A genius called Brian Moore introduced us to his weird and wonderful puppets. It was as if the young people of the south London dormitories had woken up from a long suburban slumber.

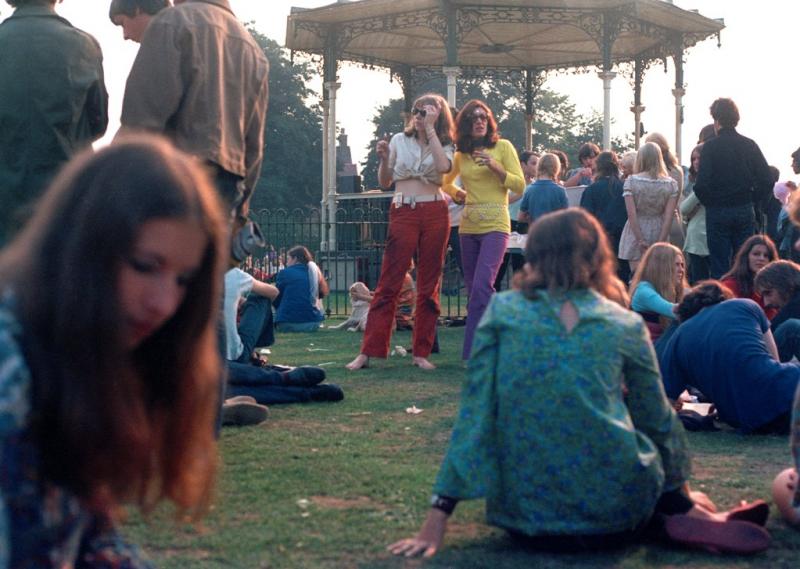

The Beckenham Arts Lab peaked on 16 August 1969 with a free festival staged at the Croydon Road Recreation Ground. I did most of the organising with help from Angie (soon to be) Bowie and some of the more practical Growth people. The festival aimed to raise funds for the Arts Lab and we brought it into being hippie style – on a wing and a prayer. David's father died shortly before the event. He was in deep grief and couldn't muster much motivation. His contribution was to phone musician friends and hope some of them would turn up.

It turned out later that our free festival was probably the first of its kind in the UK and has achieved legendary status. It was a wonderful afternoon in brilliant sunshine, everyone (except David) was blissfully happy and even the late PC Sam Wheller had a great time - and apparently parked his sense of smell.

The single of "Space Oddity" had just been released and DJ Tim Goffe played it many times between acts. David performed and compered like a true professional, but off stage he was rude and miserable – especially when we jubilantly discovered we had made the equivalent of £800 in today's money – by selling posters, burgers, teas, candy floss, crafts and so on. Imagine our surprise when the song "Memory of a Free Festival" came out as the last track on David's second album.

“We claimed the very source of joy ran through

It didn't, but it seemed that way

I kissed a lot of people that day “

As far as I know he didn't kiss anyone – but the song has a place of honour in the Bowie annals – an anthem in praise of the legacy of the 1960s.

I left the Arts Lab after the festival and never went back. I remained friends with David and Angie while his career fell into the doldrums again post Space Oddity – and even when his talent finally exploded into worldwide recognition with Ziggy Stardust.

Then the Bowie family – David, Angie and Zowie/Duncan - left Beckenham and disappeared out of my life. End of chapter, I thought. I was wrong.

If you figure in the career trajectory of a star who achieves iconic status and the fame that goes with it, there are always journalists, authors and fans on your case. I thought all this had simmered down until in August this year I was contacted by Natasha Ryzhova Lau (pictured right with Mary Finnegan) – a Russian fashion designer and Bowie fan living in Beckenham. She was appalled to discover that the Victorian bandstand where David played in 1969 was dilapidated and urgently in need of repair. No money was forthcoming from a cash-strapped council, so Natasha decided to stage a fund raiser by recreating the original event as Memory of a Free Festival.

If you figure in the career trajectory of a star who achieves iconic status and the fame that goes with it, there are always journalists, authors and fans on your case. I thought all this had simmered down until in August this year I was contacted by Natasha Ryzhova Lau (pictured right with Mary Finnegan) – a Russian fashion designer and Bowie fan living in Beckenham. She was appalled to discover that the Victorian bandstand where David played in 1969 was dilapidated and urgently in need of repair. No money was forthcoming from a cash-strapped council, so Natasha decided to stage a fund raiser by recreating the original event as Memory of a Free Festival.

Once again the Bowie charisma worked its magic...especially when Natasha heard that the man himself would contribute signed memorabilia to be auctioned for the bandstand fund. When this news broke media interest went ballistic.

On Sunday 15 September 2013 about 1,000 people gathered at the Croydon Road Recreation Ground for an event steeped in nostalgia and soaked by torrential downpours. But beneath a canopy of umbrellas everyone experienced the same 1969 level of intense, almost transcendental joy. The American singer-songwriter Amory Kane flew in from San Francisco, joining the guitarist Bill Liesegang for the headline performance. Both of them played in 1969. About 20 original Arts Lab people were in the audience – all of us 60-plus wrinklies and one in a wheelchair. The festival made £6,950 for the bandstand repairs.

There were cheers when I suggested to the crowd that the energy and ideals that generated much positive change in the 1960s were badly needed right now. Then I had difficulty maintaining composure when one of the organisers, Darcy Debrett, told me that the Beckenham Arts Lab has woken up from its 40-year siesta and is back in action.

Add comment

more New music

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Comments

David created a dance for me

Hi Tim,