Wilko Johnson (1947-2022): The Bard of Canvey Island | reviews, news & interviews

Wilko Johnson (1947-2022): The Bard of Canvey Island

Wilko Johnson (1947-2022): The Bard of Canvey Island

Snug-bar confessions in an epic Canvey Island encounter with the late Essex great

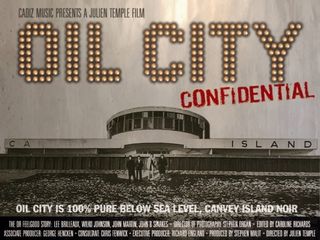

Wilko Johnson, who has died aged 75, enjoyed an astonishing afterlife while he was still alive. After Julien Temple’s Dr. Feelgood film Oil City Confidential (2009) restored his crucial former band's profile, a terminal cancer diagnosis in 2013 perversely flooded Wilko with the wonder of life, leaving this melancholy soul content for perhaps the first time.

Renewed, surreal popularity climaxed when Wilko played Chuck Berry’s “Bye Bye Johnny” for surely the last, tear-soaked time at Camden Koko that March. And yet, a doctor's suspicion of his continued vitality revealed a less aggressive cancer. Minus a melon-sized tumour and much of his innards, Wilko lived. A second Temple documentary, The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson (2015), meditated on this strange interlude. “I’m supposed to be dead,” the guitarist marvelled, back on home Canvey Island turf. “And here I am watching the tide come in.”

The following 2009 interview happened just before that second act, with even Oil City Confidential unfinished, full of charismatic snug-bar confessions from a then forgotten man.

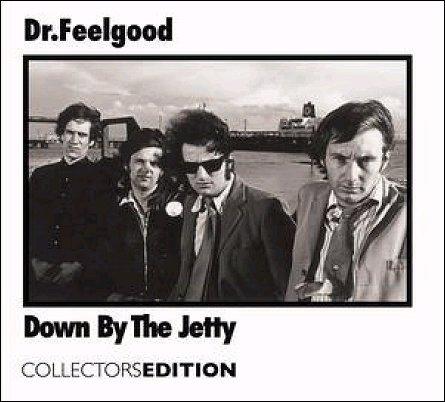

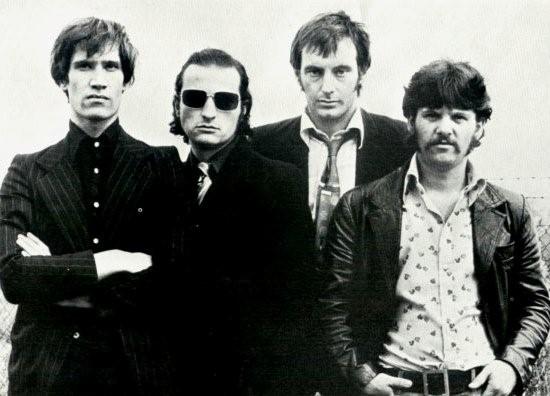

In Oil City Confidential, Julien Temple’s exhilarating new documentary on Dr Feelgood, the first thing you’ll see is the spidery, alien movements of the band’s guitarist Wilko Johnson, as he looks out over their Essex heartland, Canvey Island. The film is a sort of prequel to Temple’s Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten, digging into the early 1970s pub rock scene the Feelgoods ruled with their hard, sharp R’n’B before punk, lessons learned, stole the stage. Footage shows them to be as thrilling a live band as the UK has seen, Wilko the classic, black-garbed guitar gunslinger patrolling the stage with a manic stare, at the right hand of prowling, threatening singer Lee Brilleaux.

Johnson left the Feelgoods acrimoniously in 1977, going on to a solo career potent enough to inspire Manu Chao, among many others. Brilleaux stayed with the Feelgoods till his death from lymphoma in 1994. The tales that accrued around him were of a fearsome but kindly Essex gentleman drinker. Johnson is a less explicable, darker figure: as waywardly fascinating as Temple’s more famed punk film heroes.

Ever since I can remember, I liked to boast to people I was born below sea level, and this gave me something special

“Wilko was a revelation to me,” Temple tells me, as he wrestles with the film in an editing suite off London’s old Tin Pan Alley, Denmark Street. “He is the poet of Canvey Island, his songs are fused with the Canvey sensibility, humour and poetry. He is interested in William Blake, Milton, Marlowe. He can quote endless speeches from Tamburlaine. He’s one of the six Old Icelandic speakers in England. He learnt it so he could read the Sagas in the original. Anyone who can do that is pretty out-there. He’s a bit like William Blake, Wilko, actually. There was that divide in the band, between the others, who were pretty down-to-earth. And Wilko who had these more visionary notions of what a journey through music can be. I think he’s one of the great English eccentrics, a great national treasure, waiting to be discovered.”

Johnson’s initial electric energy in the film is countered by moments where he turns inward. The great hurt of the death of his long-time wife Irene from cancer in 2004 is one eventually revealed cause. “When you meet him you’re aware of this dimension of some kind of pain, and slight paranoia,” Temple says. “He’s fantastic in the film - the kinetic, fractured physical energy of the guy. When I saw him in the Seventies, it struck me like Kabuki. That extreme. Filming him was really interesting - totally acting out every word he said, like he was on guitar. And then one of the next times, he was like a husk - like someone had left the battery [on the car] on all night. Substance abuse? I don’t know.”

When I take the train to Canvey to meet Wilko on a chilly, grey afternoon, the island, presented as a mythic place of weird shacks and refinery flames in the Feelgoods’ music and movie, doesn’t disappoint. We sit in the bar of an old band haunt, the Monico Hotel. “Milk and Alcohol”, the Feelgoods’ only Wilkoless hit, comes on the jukebox. Wilko, once teetotal, warms himself with whiskies as we talk. The wired charisma and freewheeling wordplay are intact. The now bald, long-skulled head of the still black-garbed 62-year-old adds to his urgent presence. Sadness at his wife’s death is an undercurrent that only once almost spills into tears.

When I take the train to Canvey to meet Wilko on a chilly, grey afternoon, the island, presented as a mythic place of weird shacks and refinery flames in the Feelgoods’ music and movie, doesn’t disappoint. We sit in the bar of an old band haunt, the Monico Hotel. “Milk and Alcohol”, the Feelgoods’ only Wilkoless hit, comes on the jukebox. Wilko, once teetotal, warms himself with whiskies as we talk. The wired charisma and freewheeling wordplay are intact. The now bald, long-skulled head of the still black-garbed 62-year-old adds to his urgent presence. Sadness at his wife’s death is an undercurrent that only once almost spills into tears.

NICK HASTED: How did you get involved in the film?

WILKO JOHNSON: Chris Fenwick, Dr. Feelgood’s manager, phoned me in spring last year. He said to me, "Julien Temple wants to make a film about the band." I was a bit nonplussed that such a person could be interested. And also how it could be done, because when we were doing our thing, nobody had video cameras, there was very little footage, and of course the band has been dead a long time. But as soon as it started, it was fantastic. The first thing was he was filming some interviews over at the oil depot. And if you grow up on Canvey Island, this oil depot is always part of your consciousness. Furthermore, he was doing it at night, and projecting film of Dr. Feelgood up on the side of one of the tanks. In the nighttime, with these big silent images of Lee shaking his fist, being there was…dream-like. [He laughs] I wanted to stand there for a long, long time. “This is strange…whoever would have thought?” And it’s carried on like that.

The next day, we were filming on the street corner over there, where we used to play when we were lads. And I was standing in the bar, with my son. He’d got himself a job in Dubai, and he was going to leave the next day. I’m looking across his shoulder, and out on the street I could see this corner, where I remembered being 18 years old playing “Rock Island Line”, thinking, “Oh, you’re going to Dubai tomorrow.” I wanted to fall on his shoulder and start weeping. You can’t do that kind of thing on Canvey Island. We were there, and now I’m standing here, and Irene, his mother, is dead and gone - a whole lifetime telescoped into this image. I just said to him, “Son, I cannot do justice to this situation.” Yes, it was food for thought. Of course [Feelgoods bassist and drummer] Figure and Sparko were there, looking at these familiar places - nice memories, really. And thinking, “Oh, man. What the hell happened?” [Laughs] We cocked it up at exactly the right moment - blew it all to pieces.

For you and Lee growing up, Canvey itself and rock’n’roll and the blues seemed to give you these really vivid, literally insular fantasy lives. There was powerful imaginative stuff all around you.

For you and Lee growing up, Canvey itself and rock’n’roll and the blues seemed to give you these really vivid, literally insular fantasy lives. There was powerful imaginative stuff all around you.

It’s funny, I can remember when I started playing guitar, as most teenagers do - or did - getting interested in certain kinds of music, and feeling, “Oh, man…” You feel so hopelessly suburban. “Why was I not born and raised in some shack on the Mississippi delta?” But then, when Dr. Feelgood started, we began playing with ideas like that about this place, and realising that actually it’s got a character. And starting to incorporate that into what we were doing, and realising, wherever you come from, rock’n’roll lifts things from the mundane. I wish I could go back and explain to that boy, “Listen, there’s nothing to be ashamed about, coming from Canvey Island. It’s pretty funky, actually.”

Obviously the ideas I had about it [Mississippi blues] then were complete fantasies. You listen to Howlin’ Wolf, “Smokestack Lightnin’”, and you think he’s in some shack singing away. But the guy wanted to stay in a five-star hotel, and quite right too, because he was a star, man, he didn’t want to be living in no shack. Fantasy is so much part of it anyway. We were doing it ourselves, a lot of the time deliberately. But, we grew up and learned our music in the shadow of these huge towers.

If you think about Canvey - its ex-East Enders and their kids and their kids’ kids, living on an island below sea level, with these belching flames coming out at night - it’s an odd situation…

It is. Certainly ever since I can remember, I liked to boast to people I was born below sea level, and this gave me something special. What it was I don’t know [laughs]. My own children were born up the hill, in a hospital. But me and the wife, below sea level.

Were you telling tales of Canvey as Oil City to yourself, before you did to journalists?

I passed the 11 Plus, and went to school off Canvey Island [in Southend]. And there was a certain thing - boys from Canvey Island travelled there on steam train. And in those days it used to get very foggy down here, you know. And on such days, we’d leave early, to catch the trains, and a note would come round, “Canvey boys can leave at half past three.” And in those days a lot of people were reluctant to come here; I think they suffered from a lot of delusions about the place. It was a little bit Wild West. The houses did tend to be made of wood. It made me first of all, when I was quite young, a little bit ashamed, coming from Canvey. But then, I started to realise the potentialities there. Music fitted in well. When we started to play rhythm and blues - beat music - and copy Chicago musicians, it wasn’t fashionable. I think we were something of a curiosity. And that tended to make you even more - “That’s right, we’re from Canvey Island, and we’re playing R’n’B!” We were playing just as an amateur band, round here locally, for a couple of years. Then we went to London, and the whole idea of it had gelled by then. We were absolutely unknown in London, on what they called the pub rock scene - a term I really hate. We were unknown, but what we had was a couple of years putting this whole musical fantasy together. And of course it had an impact.

Go out in the evening, walk into Dingwalls, people nudging each other - man, it feels good

In the film you recall it seeming like “the lower end of the sky was limit” for the Feelgoods in London. But actually, there was a moment when you were the biggest band in Britain…

After we’d started playing London gigs, something changed then. Very, very quickly, we were attracting big audiences. Later, some bigwig had come to see us. And driving back, on the flyover over the A13, I remember looking and saying, “I wonder what’s gonna happen?” I knew something was going to happen. And for goodness’ sake, this could be something enormous. Yes, that was one of your moments of travelling hopefully! A moment on a flyover - that’s rather symbolic, isn’t it? [laughs]

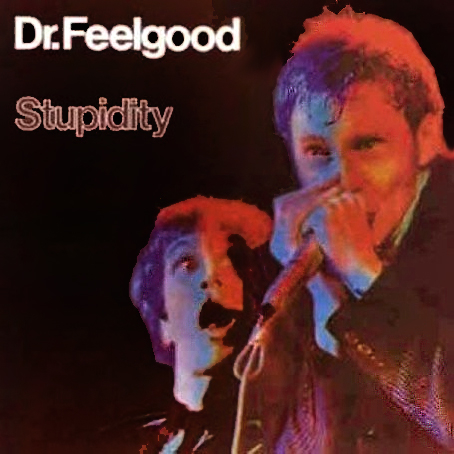

I know you really admired the Stones. Was there a point after you’d had your number one album [the raw live LP Stupidity in 1976, pictured below] that you thought, not only the lower end of the sky’s the limit; that you were going over that flyover, straight up?

The label [UA] got slightly worried after that, because we’d got signed by CBS in America - they loved us, they were really going to do a job on us. They started saying, the next album, they wanted input, they were going to put a lot of money in. They wanted an American producer. But this number one had happened, and I didn’t have to do as I was told [as Wilko had insisted on a genuinely live album, not the usual remixed and replayed job wanted by the label, and been proved right]. I didn’t make any trouble. But of course during the making of that next album in America, we split up.

In America, was the pressure you felt attached to the thought you could be big like the Stones?

In America, was the pressure you felt attached to the thought you could be big like the Stones?

No. In America, and everywhere by that point, we were being looked on as something quite special, which actually we were. I tell you what, that feels great! Go out in the evening, walk into Dingwalls, people nudging each other, man it feels good. And I didn’t have any fears about any catastrophic nosedive that would change people’s minds. I knew that we did what we did and we did it well. It could come into fashion or out of fashion, but…

I’d already been to university, Kathmandu, been a hippie, before that flyover moment - possibilities I’d never dreamed of. I wasn’t going to descend into a nine-to-five job: the whole world was there in front of us. Nice feeling. There was no fear. When I got the fear, I was sitting in a room, they want a new album. Crap, I’m writing it… it’s impossible to look at it objectively. Stage-fright - I used to get it back then, man: 7,000 people out there wanting to see you. Fear used to express itself with me feeling very tired, just wanting to curl up in a corner and, leave me alone. And you’re scared and scared.

You played 320 gigs one year. You can’t survive that for long. The traditional idea is you were the John the Baptists of punk. Watching the live footage, you look more like what you probably wanted to be, a pre-Beatles great American roadhouse band, doing absolutely everything to get over to the audience, songwriting not the main purpose.

I think so. Certainly a lot of the music, and a lot of the attitude was like that. We wanted to look sharp. Just because I’d been in audiences seeing fantastic guys doing this thing, and I loved it.

I’m amazed Lee saw Howlin’ Wolf in Romford.

Yeah, man. I saw Muddy Waters (pictured above right) several times. First time was in the Sixties, the last time in Atlanta in 1977, something like that. He was sitting down then, old. There was a special magic these people had. And these people were great artists. I was in Atlanta with Lee, at the CBS convention. We were guests of honour there, blue-eyed boys. We were getting very cool. And then Muddy Waters comes on, and on his second number, he hit a guitar solo, did another 12 bars, and I didn’t care about being cool any more, and I just jumped to my feet. He did that one song, “The Blues Had a Baby and They Called That Baby Rock’n’Roll”. I was crying. All my cool was gone. Fantastic, fantastic. I was feeling, he’s acknowledging us. Me, looking at someone like Muddy Waters, feeling like a stupid child, actually. But I know full well that when we were in front of our people, doing our thing, we were bringing out those emotions with people just the same.

In the footage, you’re looking at Lee all the time.

That was something I’ve never felt before or since. From the moment I met Lee, I knew he was a star. And when he was performing, he was having this power, and when we were staring at each other, that was all part of that fantasy I was talking about. You couldn’t quite explain it all. But we’re a gang here. He was having an effect on me, oh yeah.

You’re looking round like you’re his bodyguard, like you’d take a bullet for him.

Yeah. I’m looking at Lee and thinking, “I’ll do anything you want. Tell me what I’ve gotta do.” We always had that. Even when things started to go wrong, and there was an animosity between us that was serious, we never carried it onto stage, we felt that same thing. Partly because we were professionals, but partly because it was so strong. We were feeding off each other. It was the two of us. I felt like a lot of the power I had in whatever I was doing was radiating from him. It made you feel had to be right on top of yourself, you couldn’t let it go slack for a moment, because of this guy next to you. And it was the same with him. And we never, ever rehearsed this, or even discussed it. We knew what to do.

And once you start doing that, people come expecting it, so you can’t have an evening off, and think, “We’ll take it easy this evening, do some blues jams…” You’ve got to do it just as intensely every single time, because that’s what people want. And because the kicks you get from doing it like that are so much more. That still works for me now. I’m old. But I’m still thinking those silly kinds of fantasies, I suppose. If someone said I’d be doing it at 61…but why not?

Sometimes for a rock song, lyrics have to be absolutely crass

People getting the joke was important. We certainly didn’t want to look ridiculous. We weren’t a comedy group. And the aggression and the violence, we were in real and deadly earnest. But what you wanted was people to get high, and people enjoying it. Like playing cops and robbers when you’re a kid. It’s something like that.

Did you have a lot of pent-up emotion? Was it good for you to get it all out?

Perhaps. I don’t know. I think I am by nature a fairly miserable person. Sometimes when you’re playing onstage, at those best moments, you do get taken over by it. That’s a wonderful feeling. And a lot of it is that violence. There are things in this world that I hate, and there are things I would like to shoot down, and you’re doing all of that. But at the same time, it’s fun.

Are your strongest emotions coming up to the surface?

Yes... The miserable person, I have to leave off stage, that’s really of no interest at all. So I’m not expressing me - just that little bit. I’ll tell you what I mean. Ever since my wife died, it hurt me pretty badly, and I still think about her every minute. I’m thinking about her now. I can’t…God I loved her. Anyway. The only time I don’t feel heart-broken is when I’m playing. When I’m playing, I’m still heart-broken, but it’s okay. For that hour-and-a-half or so, I escape from that particular misery.

Is playing the only time you have strong enough feelings to do that?

I think so. You are in a fantasy. And you have come from this demi-world of blazing oil-stacks, and this really is an AK-47, it’s not a Telecaster. In that world, for a little moment you can even escape from…death. If when thinking about what I’ve done with my life, I’ve done that, all this time, for quite a lot of people, let those people understand that joke, and have a laugh, and just get away for a minute, then…I haven’t done too bad.

In the film, you wonder if it’s been a wasted life.

In the film, you wonder if it’s been a wasted life.

When I get the misery, which is quite often, I have to get some long-suffering female to tell this stuff to. What have I done? And what I could have done. If you look at it negatively, it can be, “You’re a mountebank!” You’re leaping about, and it’s really a kind of foolish thing. And sometimes I look at it like that. But it would be absolutely churlish to sit and complain.

The film shows songwriting came hard to you. Was that because you had such high expectations of yourself? You said if you weren’t a great writer by the time you were 21, you’d slit your throat. Did you know too much, with your literary mind, put too much pressure on yourself to do something great?

Literature is a different thing from songwriting. Sometimes for a rock song, lyrics have to be absolutely crass. They have to be understood straight away, at loud volume, in confusing circumstances - a series of slogans. Generally my songs start with a guitar-riff. You get a mood, and need a lyric in keeping. Then, for me, you struggle away. I try and make them good. You think, all that effort for these few lines of doggerel.

Were you more self-conscious about the whole thing than the rest of the Feelgoods? The snapping point for you leaving was when you wrote a personal song.

The whole fantasy we were talking about… I tend to sit there and analyse it. And perhaps I was more… fanatical about it than the others. About everything, really. I took this joke more seriously. And I think there was an element of that when we broke up. But really - why should that have happened? I don’t know. When someone asked, I could not really give an honest answer. I have to admit, looking back, that sometimes I was an arsehole. I could be hard to get on with. Then again I could give reasons for that. And that kind of thing does get very strong when you’re on the road. And especially if any success is happening, the pressure and worry of that is very strong - so it’s quite easy for people to flair up. Because they’re freaked out and frightened. You’re just frightened, really. Start smashing things because you’re just so scared of what’s going to happen. Stuff like that all led to a particular moment. I would like to travel back in time and give a few general words of advice.

It seems like any band that people really care about, going at such a pace, is almost designed to burn out.

I think that is true. When it was happening, and people adopted positions, I was so adamant about mine, and I could see that, wow, it’s breaking up. But I could not do anything about it. It’s a shame. And it can seem silly now. And I don’t think it did any of us any good. But when it was happening, there was that intensity about it. Being sensible and reasonable has really got no place in it - to do it properly.

Did you speak to Lee much, after the split?

We hardly ever met. I can remember a couple of occasions, maybe seeing each other at gigs, where we’d both be looking at our shoes. “You alright?” My band, we’ve worked a lot the last 20 years in Japan, and one year, they had arranged it so Dr. Feelgood were in Tokyo and Osaka. The Japanese, God bless them, worked it so we were always kept apart. We watched each other from the wings, of course. And goodness knows what thoughts were running through our heads. But we never talked, any more. And when he was dying, I did want to go and see him. My brother went to see him, actually. But I needed one of the Feelgood's people to come and get me and take me there. Nobody’s fault, but it just didn’t happen.

Once we’d split up, I determined to walk away, not to bury the animosity, but to hang onto when it was great. After a while, I was in a different world.

One thing the film brings out is that Dr. Feelgood’s story and music would be potent and important even if it hadn’t helped cause punk. It’s just as good as the Joe Strummer film.

Really. That’s good, then.

The first half shows you lot growing up in Canvey - it has faded, pastel home movie footage from Lee’s family of people in their bungalows’ gardens in the Fifties; that world seems an almost vanished, exotic place now - and it’s just Essex after the war. Biblical floods. It’s an extraordinary time and place you came from. Your lives are rich.

Really? Maybe I’ll get a little bit of respect from my son [pleased laugh]. I was puzzled by what he [Julien] could do with these shreds of evidence. And then sometimes I’d be thinking, “I wish everyone would go away and just leave me alone.” Obviously it’s a long time ago, and I’m still working as a musician. And obviously I cannot dwell on what that was and what it might have been. Because it could make you quite bitter really, couldn’t it? Quite an achievement to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

It’s still a victory - the film shows that.

That is nice to think about, that when I’m gone, it hasn’t absolutely…gone [pleased laugh].

Julien said it fascinated him to remember that for at least a year, you were the biggest, most important band in Britain; then because of punk, you were washed away - and you caused the wave.

Makes it the best policy for me to not dwell on that. I started meeting the punk musicians just after the bust-up - in the aftermath I met Joe Strummer, John Lydon, I was sharing a flat with [the Stranglers’] Jean-Jacques Burnel. Some funny things happened there. I thought I’d be condemned as a dinosaur, but I found they all dug us, and were friendly. I thought the Feelgoods, with our success, were going to kick off another R’n’B thing. The punk thing was quite different. Guys so much younger, inexperienced, to put it mildly, as musicians. But they had certainly seen us, and what they did derive was the sheer energy.

[I turn the tape off, the interview over. But Wilko has more to say about Irene. The tape goes back on.]

[I turn the tape off, the interview over. But Wilko has more to say about Irene. The tape goes back on.]

I have actually found myself with a glass of whiskey at the bar, telling the barman… oh fucking hell I miss her. She was an extraordinary, lovely person, and we were just together so long. We were 16 when we started going out. Together 40 years….Everything stopped. Every road I go down, the road isn’t going anywhere, it’s leading away from her grave. She told us, long before she was sick, she wanted a green burial - near Harwich, where they plant an English deciduous tree over every grave, with a wooden plaque. I’ll be next door. At the funeral, they played Leadbelly, “Goodnight Irene”. Fucking hell - I don’t know if that was the saddest thing. Her mother was old, demented, we hadn’t told her Irene was sick. When the female vicar told her she was dead she went [high-pitched Glasgow voice], “Oh, no!” I think that’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen. But we struggle by.

That wasn’t really part of the plan, that happening. Suppose I thought one day I’d be dying of one excess or other. It’s sad.

Julien called you the bard of Canvey Island when I spoke to him. Like Ray Davies in north London, you’ve marked out a territory.

I certainly, in the Feelgoods' time, made a conscious effort to reflect and dramatise the landscape here. Since Irene died, I ain’t written anything. I tell a lie - last Christmas the band were in Japan with Sheena and the Rockets, pretty good friends; for them to play on their 30th anniversary, I found a song I’d written 30 years ago. In the middle of doing all that, I suddenly realised I’d written a song. I wanted to play it; we learned it for the gig the next day. I hadn’t felt that kind of excitement for a long time, and it gave me these memories. Maybe I should start coming back to life, I don’t know. Whenever I get these little twinges, it’s quite life-affirming. All you’re doing is saying, “I love you, baby”, or “I hate you, baby”, but…

I wish I could write the novel. Scrabbling around all this stuff for Julien, I find tattered bits of typescript from years ago. The difficulty with any creative thing is I appreciate the really great stuff, the presumption of trying it myself is inhibiting.

I know you’ve got a passion for astronomy - and a secret observatory on your roof.

I’ll tell you what it was. When I was in the Blockheads, in 1978, we were offered a tour of Australia. Ian Dury was already there in Melbourne: “I want two whores now!” I go to the roof of the hotel, with the southern skies above, and I’m lying on the lido, and I see the stars swarming about - they were fireflies. When I calmed down, I thought I’d look into what real stars look like at home. Then on tour in New Zealand, I noticed the moon was upside down. And I liked that. And years later, I went outside with my son’s cheap pair of binoculars, and I could see Jupiter, and its moons around it. Our garden was so small, you could only see a small patch of the sky. Then two, three years ago, I was sitting up with [Essex R’n’B legend] Lew Lewis, talking about these new telescopes, and how I wanted to see the rings of Saturn. I ordered the telescope about the time I knew Saturn would be rising a little after dawn. I could see a star rising over the houses opposite, and I knew it was Saturn. And suddenly, it shot across the field of view. “FUCK! Jesus Christ!” Leaves can get in the way of the telescope. You could see me early in the morning, tearing the leaves off the trees. I started going barmy, getting bigger and bigger telescopes.

The one I’ve got now is huge. I lie flat on the roof, I can stare at it [Saturn] for hours and think, "That thing exists." If someone said, “Design a beautiful object, do anything you like,” who would think of a sphere with rings round it? I’ve got a dome now on my roof, a den, it feels so great up there. And I’ve been looking at galaxies. And the speculation they can lead to… it’s beyond thought. You can just about imagine terrestrial distances. When you start getting into light years, it’s so far… and all those galaxies, that are all full of billions of stars. It’s logically obvious that there is intelligent life.

Now, we’re on this planet where intelligent life has happened. And this particular life-form, occasionally we throw up a Shakespeare or an Einstein. So it is conceivable there’s a planet where Shakespeare and Einstein are a normal level of intelligence. Their Shakespeare and Einstein have gone further. And then I start thinking, "How clever can you be?" In some ways, we’re too clever already. We don’t need to be this clever, to rule the planet, and destroy it. I look at life on this earth. But my favourite object is the Great Nebula in Orion…

A screening of Oil City Confidential at the London Film Festival on 20 October is fully booked. A limited cinema release will follow. Wilko Johnson is, as always, on tour.

Comments

...

...