theartsdesk Q&A: Director István Szabó | reviews, news & interviews

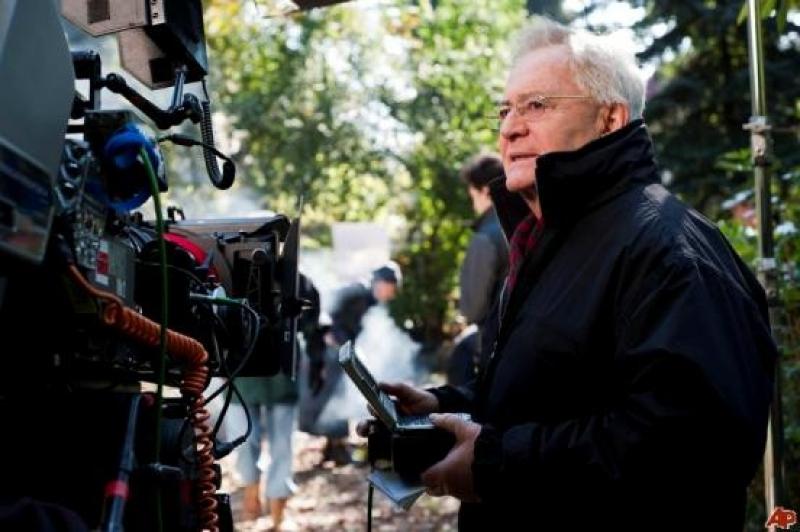

theartsdesk Q&A: Director István Szabó

theartsdesk Q&A: Director István Szabó

As his earliest success is released on DVD, the great Hungarian director looks back

When I interviewed the great Hungarian film-maker István Szabó (b 1938) in his native Budapest, he took me on a tour of the city centre on the Pest side of the Danube. On the way we were distracted by a flashy café designed to lure tourists. It was called Mephisto – after the film by Szabó, presumably, which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1981.

Mephisto, based on Klaus Mann's novel, tells of a brilliant Brechtian actor who makes a Faust-like pact with the Third Reich. In Colonel Redl (1985), based on John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me, a high-flying officer in the Austro-Hungarian army struggles to conceal both his Jewishness and his homosexuality. In Hanussen (1988), a clairvoyant predicts the rise of Hitler, luring him into the Nazi web. All three films were at least in part allegories about the moral choices required of those living under Communism. All three films were shot in German, and starred the feline Austrian actor Klaus Maria Brandauer.

In more recent years Szabó has made films in English. Meeting Venus (1991) was an operatic saga starring Glenn Close, Sunshine (1999), with Ralph Fiennes playing three characters across three generations, chronicled a century in the life of a middle-class Jewish family in Hungary. Taking Sides (2001) was based on Ronald Harwood’s play about Wilhelm Furtwängler and Being Julia (2004) had Annette Bening as a flighty actress in an adaptation of a Somerset Maugham novel.

Second Run are releasing an earlier film of Szabó’s on DVD. Apa, or Father (1966), was his second work, but his first to come to international attention. Roughly autobiographical, it told of a young schoolboy’s failure to come to terms with the death of his father – a fate common to many Hungarian children of that generation, as the film suggests in a scene in which most of a class stands up when asked by the teacher whose father is still alive.

Rather than accept the disappointing reality, Takó (Daniel Erdély, pictured right) conjures up a fantasy life, realised in beautifully filmed pastiche sequences, in which his father (Miklos Gábor) is variously a brave hero of the resistance, a brilliant surgeon, and a populist saviour. Later, when he grows up and lives through the 1956 Hungarian uprising, Takó (now played by András Bálint) meets and falls in love with a fellow student (Kati Sólyom) who has kept quiet about her past in a different way, hushing up her Jewishness.

Rather than accept the disappointing reality, Takó (Daniel Erdély, pictured right) conjures up a fantasy life, realised in beautifully filmed pastiche sequences, in which his father (Miklos Gábor) is variously a brave hero of the resistance, a brilliant surgeon, and a populist saviour. Later, when he grows up and lives through the 1956 Hungarian uprising, Takó (now played by András Bálint) meets and falls in love with a fellow student (Kati Sólyom) who has kept quiet about her past in a different way, hushing up her Jewishness.

The question of Szabó’s own identity is not dissimilar to that of the Sonnenscheins in Sunshine. His own family is of Jewish medical stock, long since Catholicised by 1944, when István was five and the SS at its most brutally efficient flushed the vast Jewish population out of a city that was once anti-Semitically dubbed “Judapest”. His immediate relatives were not rounded up. “Part of the family was, yes,” he told me. “But I don’t like to talk about it.”

In one powerful scene in Father, the adult Takó is an extra in a film re-enactment of Hungarian Jews being herded out of the city. The fierce, even dictatorial director howls at Takó to step out of the line of victims and play a collaborator marshalling them with a rifle.

Glenn Close once told me she “learned a lot about acting from István. But he can be fierce”. At least in interview he is watchful, austere, even a little icy, and not inclined to play to a Western journalist’s stereotypical notions of what it was like to be an artist under the communist regime.

At the end of my time with Szabó, we found ourselves sitting in the splendid Art Deco surroundings of Café Gerbeaud, where he shot a scene in Mephisto in which an English journalist slaps Brandauer’s character, saying, “That’s for what’s happening in Germany.” In such a resonant setting I realised that much of Szabó’s distinguished career has been the pursuit of the perfect close-up, of the one image that offers a window into the soul. What would a close-up reveal of the man eating a square slab of souffle opposite me? A lived-in face that, in the odd smile, now and then flashes a ray of sunshine.

Szabó ordered for me a slice of dobos, a cake in which layer upon layer of white sponge and chocolate icing are laid in a painstaking stack. For Szabó, film-making is a bit like that: no one goes deeper. It’s a lifetime’s work examining a nation’s conscience. In rich, idiosyncratic, sometimes broken English - he much prefers German - the director talks to theartsdesk.

Watch the opening of Father

JASPER REES: Which side of the city do you come from?

ISTVÁN SZABÓ: I was born on the Pest side and then my parents moved to the city of my father, 60km from Budapest. He was a medical doctor and started to work in the hospital of his father, and then after the war we moved back to Budapest after the death of my father. First I lived on the Pest side at my grandparent’s place and then my mother moved to the Buda side, and so I finished middle school on the Buda side and then after university I married. Since I married I am living on the Pest side. I was married in 1961. I don’t have children.

Have you always been a city family?

They came from the countryside, north of Hungary, now it’s Slovakia. Nitra. I think my grandfather and his brother went to Vienna to study and then my father finished university and his older brother finished the university of law, they came to Budapest and from Budapest my grandfather accepted a job to be the first medical officer in a town 60kms from Budapest. It happened at the end of the 19th century, 1890s. When my father was born in 1902 my grandfather was the medical doctor of this small town.

I was born in 1938 and since I am living I had a royal Hungary, with Admiral Horthy, then I had a Fascist government with Ferenc, then we had the war, then we had a very short democratic period with many different parties, then we had the Stalinist dictatorship, then we had 1956, then we had the second communist period with several changes and then the last political change now. So only in my life I had eight different changes and having the changes we had different names for the streets in Budapest. It’s quite funny that without moving from your flat you had six, seven, eight different addresses following the political regimes.

I practised in my life what is from people living in the country say: "From today everything was different." But it’s quite difficult to follow if people are saying that they had nothing to do with the former system; they know that of course they had. I wanted to tell in this film this heavy fate that you have to carry in your life if you have to deal with all this political difficulties they have in Middle Europe. But believe me it is not only Hungarian story. It is the story of Slovaks and Czechs and Austrians.

What echelon of society did you come from?

Middle class. A little bit higher middle class. Intellectuals, medical doctors, lawyers.

Your family was decimated by the war?

Yes, but everything that we had helped us to survive, and the mentality was clear and kept by my grandparents and through them my mother, because my father died when I was six. So for example in my family I learnt from my grandparents and my mother and my aunt what is the real meaning of the communist system and the real meaning of the Stalinist system. I listened in school and they told me please, “Never tell what you heard at home,” and of course I never told, but I had my opinion and I shared it with my mother and even with some friends who had a similar background to me.

Opposite the house where I was living with my mother and sister, I had friends and family from teachers, a boy and a girl. They were my best friends. We discussed as 10-year-old kids climbing at the top of the tree. So we had our opinion. It’s not true that people were not informed. Of course just after the war was a fantastic atmosphere for democracy and changes and socialist feelings, yes, but after the terrible Stalinist period started I cannot imagine that people couldn’t feel what happened, because we as 10-year-old kids knew.

How were you able to tolerate it?

Everybody tolerated it. They knew that it’s not allowed to speak, that’s all. We did everything that the Pioneer movement, a Stalinist youth, asked us. We sang the songs and we did everything and it was funny to do. It’s not a big deal to speak two different languages.

How did you get into film?

I wanted to be a medical doctor. Today I would like to be a medical doctor, because this is what I have in my blood. I was 16, then my friends in the school created a theatre and invited me. I realised very fast that I am not a talented actor but I liked very much to help other people to do it. So I became a little bit one of the directors of the school theatre. I got an interest of theatre.

And then after a year of being in love with theatre I got accidentally a book about cinema written by Béla Balázs, The Visible Man, about silent film. Reading this book it was like a light to understand that film is more interesting than theatre. I have to tell you, it’s ridiculous but it was enough for me to go to film school to learn the profession. I went at 19, for five years. Then I became an assistant director and at the same time I did short films, and they were successful and I got my first feature film possibility when I was 25. Today a young film-maker’s age is 40, 45.

What are your memories of 1956?

I was very young. I was 18. I was in the school and on 23 October we heard that there are some demonstrations and we went to see the demonstration and after dark we went home. The next day I went to go to school and my mother told me, “Have you heard the radio? You cannot go to school.” I lived at this time on the Buda side.

Did you find it difficult to make films in the Sixties?

Did you find it difficult to make films in the Sixties?

I think the first period of the Kádár regime was very hard, after 1956 and the beginning of the Sixties. But at the beginning of the Sixties Kádár changed the mentality of the regime and became probably from need to have communication possibilities with the Western countries, or he changed his mind about his system or his philosophy in Hungary. But only in Hungary the system became more liberal, only to show the Hungarian kind of socialism gives a kind of private freedom too.

They changed the economical system, they accepted private businesses, and especially in the film business we got a kind of freedom because the people responsible for cultural policy, I think they understood with motion pictures they can show all over the world the Hungarian system is acceptable because it gives freedom to its artists. And so to the Hungarian film-makers it was allowed to criticise the regime. If you say the most important film from the Sixties, like Round-Up or Cold Days, you can see that all those films try with real success to criticise the ideology of the regime. Even Round-Up analysed the system of the regime so fantastically and so deeply it’s not imaginable that it was allowed at this time, and the reaction was very, very positive, because all over the world the Hungarian film was very deeply appreciated or accepted.

So film-making was not so difficult although some colleagues of mine had difficulty with censorship - we had some taboos not to touch. It was impossible to touch the Soviet empire, it was impossible to touch the communist worker-class movement, it was not really to touch a kind of very Catholic morality which was deeply accepted by the Communists; erotic or soft pornography were not really allowed.

Did it get easier for you personally to make films in the Sixties?

If you don’t mind, I would like to use the expression "we" and not "me". We had some difficulties, with every film, me too. I had some discussions about my screenplays, of course, and sometimes I had to change something, but they were not essential changes, not really important. So if I would like to please you or people who would like to have negative information about the period I can please you and tell you some negative experiences, but looking back I have to tell you over all the small or ridiculous or sometimes heavy difficulties, it was easy.

I can tell you about every film of mine, difficulties, bad days, terrible discussions with people that were responsible for the film politics, some terrible weeks desperately wishing to change everything around me, but looking back honestly I have to tell the way was not so complicated.

If I am telling you difficulties I am telling you the truth. I am telling you the realities. Only I am not reassured that the realities are so important, speaking about the truth. Finally I did the films, finally I did Mephisto (pictured above) and Colonel Redl (pictured below). But I had some colleagues that had real, real difficulties, it’s also true.

Although erotica was frowned on under the Communists, it nowadays seems to be a country which is comfortable with its own sexuality.

Although erotica was frowned on under the Communists, it nowadays seems to be a country which is comfortable with its own sexuality.

I think it’s an operetta façade. Like many things in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, a beautiful face and behind the curtain we are different. It’s exactly the same in Austria or with the Czechs. It’s so fantastic to see how the mentality of the Austro-Hungarian Empire is deeply in the blood of the country and deeply in the morality.

The most important problem is the feudal mentality: an internal need to have somebody above you, somebody who dominates you and then your responsibility is smaller. So you have somebody above you who is able to take over the responsibility and to decide about your problems and your life. You are thankful and you can hate him because he is the person who will decide about you, so you can hate and you can rebel against him, but you are happy to sit around his lunch table and you are waiting to be caressed by him and to be decorated by him. It’s a servile mentality and this is the mentality which is very open to create a picture of enemies, open to use scheming and plotting.

Of course, if you have someone who dominates you and is able to decide then you don’t need to think and you don’t need to have a bad conscience. You are not able to think about your past and you are not able to think about what you did. So that’s why Austria, like several Middle European countries, never accepted to look into the mirror and think about what they did in the Thirties and the Forties.

Austrians are happy to say, “No, everything that happened in Europe in the Thirties and Forties was done by the Germans,” which is not true. Austrians are very happy to think that Beethoven was Austrian and Adolf Hitler German, although the reality is opposite. But they are not able to learn it. This is what I mean by the feudal character: being open to domination. The danger in every Middle European country is there because it’s a part of the mentality.

Democracy is something to learn and I think you need time to learn that if you have a different opinion from me then maybe we can discuss it and it’s not important to shoot you. Maybe it’s not important to create from your face the portrait of the enemy, only because another colour for jumpers to what I like. To learn to discuss, to learn to accept other opinion, to find a compromise which can help us to find a way is something to learn. It belongs to the school system, to the family, it belongs to many things, but the system which needs a dominant person in every family doesn’t help.

"What do you want from me? After all I'm only an actor": the climactic reckoning in Mephisto

What did the old Empire mean to the regime?

It’s the past - they never cared. I can tell you something very important concerning this question. I think the freedom of the Hungarian film industry, or the secret of that freedom, was not only in the wish of the regime to sell itself as a liberal regime. The other part of the secret is that the Hungarian film-makers found a flower language to tell the story that we wanted to tell. And the flower language is to tell everything you would like to tell but cover with something which is a good excuse.

For example, Miklós Jancsó told exactly the system for the hard Communist dictatorship concerning 1956 but he used the costume of another century. He told in Round-Up everything about what happened after the 1956 revolution but it was an 18th-century story in the film, so when some hard cultural politicians, especially in Russia or East Germany, asked the Hungarian film authorities, “What is this counter-revolutionary rubbish?” they said, “I’m sorry, we don’t exactly know what you’re speaking about, it’s about the last century.” So the Empire or the Thirties was the best excuse to tell everything you wanted, and this was the flower language.

And this flower language, this kind of storytelling, was accepted by the authorities and the audience and by the foreign audience and everybody knew our subject but because it was covered by different-coloured flowers it was accepted. So the Empire was very, very helpful for us and to me personally for telling the stories I wanted to tell.

Is Mephisto also about coming to a moral compromise with Communism?

I don’t want to say that it’s exactly the same because the Nazi philosophy was harder and they offered really to kill people. The communist state did it behind a mask, of course, but there were many similarities.

I don’t think there’s a big difference between hard right wing and hard left wing, and people are hardly on the militant left side or hardly on the militant right side. They are from the mentality and from the soul very, very similar to each other. Even I can see having my experiences how easy for some people to change from the militant left side to the militant right side, and how happy they are to change, like Mr Milosevic.

Can I ask about your father? By the time you were born, was your family’s Jewishness in the past?

It was in the past so my father was a medical doctor in a religious hospital owned by Catholic nuns. His situation was not so complicated. The family was Catholic. I am not practising religion. Part of the family, yes. I don’t like to talk about it.

I noticed that you have a character called Dr Sonnenschein in Colonel Redl.

Doing Colonel Redl, writing the character of Dr Sonnenschein, I thought one day I would like to do a film about the story of Dr Sonnenschein. And then I did it. It’s not the same character of course, but the roots…

Every film of mine has a long process to burn, to the words. I think doing Colonel Redl I had a wish to tell the story of Dr Sonnenschein, maybe this was the first step, but then I did other films, and then it came back in the Nineties. I thought that the story of Dr Sonnenschein can tell something very, very important, and this is the identity problem.

If you think a tiny bit about the problems of Dr Sonnenschein, it’s a long discussion between Colonel Redl and Dr Sonnenschein walking after a long night, seeing the sun rise. And he, who is a higher-rank medical doctor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, is asking himself and Colonel Redl also the question about his identity, and I think Colonel Redl has a similar problem, so the question of identity is in Middle Europe really important.

Assimilation, losing identity; assimilation, keeping identity. What if somebody is losing his identity? How is the life having this crisis, this lack of identity? How can you live without having roots? Why cut roots only because you want to please a group of people or please society or reach a position to please somebody? So they are very, very important questions in Middle Europe.

But then I did other films. I was sure that I cannot reach the real questions. My knowledge is not enough for it. So I had only the dream or the wish to speak about the problem, but my way of thinking was not deep enough at this time and I knew that I have to wait. Sometimes I have ideas, or dreams, to do a film but I know that my knowledge is not enough for it so I have to wait. So I waited for about 10 years and I am not really sure that I found the best time to do it. But I was very happy to have this possibility to do this film.

One could say that the themes treated in Sunshine are also in Colonel Redl and Mephisto.

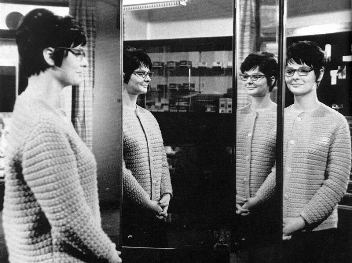

If I would like to be clever and look back and try to find out what is the energy of my films, what I did – if the film had an energy, then now looking back and seeing 10 or 12 feature films I know that I have a line, and this line is around fighting for the feeling of security, so every character in my film from Age of Daydreaming (pictured left) or Father until Confident or Mephisto or Colonel Redl or even Meeting Venus, in all films and all leading characters they had only one wish: to find a feeling of security. And this daily fight gives them conflict and energy and sometimes character problems.

If I would like to be clever and look back and try to find out what is the energy of my films, what I did – if the film had an energy, then now looking back and seeing 10 or 12 feature films I know that I have a line, and this line is around fighting for the feeling of security, so every character in my film from Age of Daydreaming (pictured left) or Father until Confident or Mephisto or Colonel Redl or even Meeting Venus, in all films and all leading characters they had only one wish: to find a feeling of security. And this daily fight gives them conflict and energy and sometimes character problems.

There are challenges from society or history or politics and of course the reaction is different having different characters. But the questions - how to find myself, how to find a safe life, how to be accepted by the society which the character would like to live in - is always the same.

It doesn’t matter that you have a little boy who would like to find his small society and he needs to tell fairy tales about his father to be accepted, or the actor in Mephisto who knows that he is very talented, he is maybe the best to do Hamlet, but to save his talent he ends up being engaged in a political movement. Or Colonel Redl, who is coming from a very small, very poor family, from a very small minority in the family, and if he would like to reach the position he can reach because he is more talented than other people, if he would like to please or he would like to be thankful to everybody who gives him possibility to climb up, then he has to find compromises, and this is the conflict.

Only now after I don’t know how many years of working as film-maker, now looking back, and suddenly I realise all my films are describing different aspects of the same problem.

Have you been telling your own story all this time?

It’s not my story. It’s maybe the biography of a Middle European generation. I can show you people from Prague, from Vienna, from Krakow, from Trieste, from all Middle Europe, that can tell you very, very similar stories and I remember when I was a schoolboy they wanted to give us some help packages with sugar and chocolate and they asked us, “Who lost his father during the Second World War?” Seventy per cent of my schoolfriends stood up. The whole generation had very similar testimony. It’s not my story. Nothing is my story. Only I belong also to a generation whose story I describe in those films.

If you had made Sunshine in German 15 years ago, would Klaus Maria Brandauer have been perfect for the role?

If you had made Sunshine in German 15 years ago, would Klaus Maria Brandauer have been perfect for the role?

There is one very major difference between Ralph Fiennes (pictured right) and Klaus. Klaus is one of my best friends and I know his qualities, he’s fantastic. But the difference is that Klaus is always dangerous. Klaus has a quality that you always have the feeling you cannot count on his reactions, because it’s always different. And Ralph has a quality to be innocent. Ralph has a soul which is behind all his dangerous part which is innocent. It’s education, it’s character, it’s life. I don’t know.

What Ralph did is to me fantastic, because he created three really deeply different characters. Three different characters are created by Ralph so precisely by his movements, with gestures, with how he walks, how he sits down, but the difference is not theatrical, he did it with very small, tiny, fine elements, and you see the difference, but it’s not ridiculously visible. I think he’s a very, very great actor.

Watch the trailer to Sunshine

Finally, would it be possible to sum up what in your eyes is the role of cinema in this turbulent life you have lived?

I don’t like to share pessimistic ideas. I think life is pessimistic and difficult enough that people sitting in the cinema experience. So I think we have to give some hope that we are able to find a way and to go forward.

I think every film of mine has an optimistic ending, which means the character we don’t like got the punishment, like in Mephisto. Maybe the person they like dies, but our morality is the winner.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Evil Does Not Exist review - Ryusuke Hamaguchi's nuanced follow-up to 'Drive My Car'

A parable about the perils of eco-tourism with a violent twist

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

Io Capitano review - gripping odyssey from Senegal to Italy

Matteo Garrone's Oscar-nominated drama of two teenage boys pursuing their dream

Add comment