Interview: Barrie Keeffe on Sus, The Long Good Friday and London's Changing East End | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Barrie Keeffe on Sus, The Long Good Friday and London's Changing East End

Interview: Barrie Keeffe on Sus, The Long Good Friday and London's Changing East End

Artful dodgers, diamond geezers and the real East End, by one of its leading scribes

Within the space of a single year - 1979 - Barrie Keeffe wrote two scripts which together summed up the very essence of the East End on the eve of Thatcherism. The first, which barely needs introduction, was the now-classic The Long Good Friday. The other was Sus, an explosive play about a black man detained by two racist police officers on the night of the General Election.

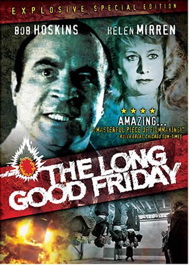

Keeffe has written numerous stage plays, including Gotcha, Only a Game, Abide with Me, My Girl and King of England, but The Long Good Friday remains his only produced film script. It created a breakthrough role for Bob Hoskins as Harold Shand, a brash gangster who finds his fortune and reputation brusquely assailed by violent, sinister, inexplicable forces: the IRA, as it turns out.

Keeffe brilliantly - and presciently - captures an East End on the verge of cataclysmic change, as the old-school hard men find their manors invaded by political forces beyond their ken and property developers circle around a Docklands that's ripe for the plucking. Why, it's even possible, Shand speculates, that East London might one day host the Olympics! Helen Mirren as Shand's classy mistress and Pierce Brosnan as an IRA hitman also experienced career lift-off in the wake of John MacKenzie's landmark film.

Keeffe brilliantly - and presciently - captures an East End on the verge of cataclysmic change, as the old-school hard men find their manors invaded by political forces beyond their ken and property developers circle around a Docklands that's ripe for the plucking. Why, it's even possible, Shand speculates, that East London might one day host the Olympics! Helen Mirren as Shand's classy mistress and Pierce Brosnan as an IRA hitman also experienced career lift-off in the wake of John MacKenzie's landmark film.

Sus, by contrast, is an intense three-handed chamber play that unfolds in a single room in the course of one night. Pulled in under the notorious "stop-and-search" laws, which enabled people (generally black people) to be arrested on the pure suspicion that they might commit a crime, one man is interrogated, taunted, physically abused and psychologically crushed by two policemen high on the prospects of the imminent Thatcher victory.

On the eve of the EEFF, which opens tomorrow, Keeffe (born in East Ham, East London, in 1945) talked to theartsdesk about starting out as a cub reporter, the transmuting landscape of the East End, cinema's artful dodgers and diamond geezers, and the continuing, burning topicality of his own two iconic works.

SHEILA JOHNSTON: Tell me how you started out as a playwright.

BARRIE KEEFFE: I worked as a journalist at the Stratford Express from about 1964 to 1975, which was when I was suddenly able to live off my writing. The seeds were planted then; it was a very fertile time, just before the end of the Krays' empire, and a lot of my plays, and some of the incidents in The Long Good Friday, came from my experiences. For instance, one of the gangland punishments, if you strayed into someone else's territory, was to crucify you to the warehouse floor. As a very innocent junior reporter, a young 18, I was sent to interview a guy in hospital. He was covered in bandages and I asked him what had happened. He said, with that wonderful East End humour, "Do you understand English, son? Well, put it down to a do-it-yourself accident."

Perhaps that kind of humorous East End stoicism is a residual legacy of the Blitz...

Perhaps that kind of humorous East End stoicism is a residual legacy of the Blitz...

Well, I remember hearing from relatives about coming out of the bunkers with the docks on fire. Harold Shand in The Long Good Friday goes on about how we're more sophisticated than the Mafia, Dunkirk spirit, sense of history and all that. But the other thing I love so much about the East End is the fabulous ethnic mix. We've always welcomed outsiders: Huguenots, Russian Jews after the revolution, Bangladeshis.... And, today, painters, musicians and filmmakers, of course - there's an incredible amount of filmmaking going on.

That vitality always kept me optimistic during the times when the National Front was marching. At the Battle of Cable Street [1936], the locals broke up Oswald Mosley's marchers by throwing tomatoes at Mosley. He looked like a wimp wincing when the tomatoes hit him but what the newsreels didn't show was that there were razor blades in them. Don't forget this is East End folklore. But it's a great story.

I thought Sus was a Kleenex, throwaway play. I'm horrified and saddened that it's still hitting a nerve

Did you ever work with Joan Littlewood (pictured above left by the bombed Theatre Royal, Stratford East)?

No, but she was my great hero. Her Theatre Workshop productions were what got me into writing for theatre. At the time I thought theatre was so middle-class and dilettante. She made it seem incredibly important and relevant. She was a big, big influence on me.

Yes, I remember reading a quote from you in which you said, "I write plays for people who wouldn't be seen dead in the theatre".... How did Sus come about?

I was writing it while we were shooting The Long Good Friday. At the time one critic called the play "instant political theatre", the implication being that it had no longevity at all, and I thought myself that it was a Kleenex, throwaway play. I'm horrified and saddened that it's still spot-on relevant and, 30 years later, still hitting a nerve. It played a big part in the repeal of the Sus law [in 1981] but of course now, under Section 44 of the 2000 Terrorism Act, more blacks and Asians are being picked up than ever. (Clint Dyer, below, plays the hapless detainee).

Did you ever consider updating it?

Did you ever consider updating it?

I feel, if it works, don't fix it. But, if I were an Asian Muslim guy, I reckon I would think, "That could be me." I'm from an Irish family and the hostility and prejudice were something I was drawing on from my own life as an Irishman in London, when the IRA was so active.

Yes, one thinks of those signs that were openly displayed in the windows of boarding houses before the first Race Relations Act [1965]: " No coloureds, Irish or dogs." Were you ever pulled in for questioning by the police yourself?

No. But there was that sort of smell, that hatred in the air. I was drawing on my experience of that fear. That prejudice, you can smell it when you're going to be the victim of it.

The dramatic conflict in Sus could have been, literally, black and white. But you made several unexpected choices. For a start, Delroy, the guy who's arrested, wasn't just standing at a bus stop or walking down the street, like a lot of people detained under the Sus law - the police do genuinely suspect him of murder or manslaughter.

The whole conceit of the play was the classic Aristophanes idea that the audience knows more than the main character does. Delroy comes in thinking, "Oh, I've just got picked up again on Sus, another waste of time, let's have a laugh." The audience - and the cops - knows it's much more serious. That was one of the aims at the beginning. The cops have got all the reasons for suspecting him - they know his financial difficulties, even though they're jumping the gun.

Another twist is that the cops are nasty, sadistic and racist, but one of them is also bright and educated - when he says he's learning foreign languages, you assume he'll be useless but then you hear him speaking French on the phone and he's actually quite good.

I'll mention that to Ralph [Brown, the actor who plays him - and whom some viewers may recognise as Danny, the druggie inventor of the Camberwell Carrot in Withnail and I] - he'll be very pleased about it! That idea of the man of culture who subscribes to a history book club was stolen from a detective I met in another context. (Brown is pictured below left, with Rafe Spall as his fellow cop).

I loved the bit of arcana relating to Wanstead Flats [a green area in outer East London], of which the policeman says that it's illegal to shoot bows and arrows there, and also illegal, under an ancient law that was never repealed, not to practise archery once a week. But, apart from the reference to Wanstead, the play could have been set in a detention cell anywhere in the UK. How important was the setting?

I loved the bit of arcana relating to Wanstead Flats [a green area in outer East London], of which the policeman says that it's illegal to shoot bows and arrows there, and also illegal, under an ancient law that was never repealed, not to practise archery once a week. But, apart from the reference to Wanstead, the play could have been set in a detention cell anywhere in the UK. How important was the setting?

I set it in East London because this was a place and people I knew, which is always a useful start. One day, when I was a young journalist, a black guy came into the office to say this had happened to him the night before. His children went into care and, the last I knew, he hadn't got them back. He was a broken, broken man. It wasn't until Thatcher came to power in 1979, that I wrote his story very quickly, though it had been haunting me for 15 years.

But Sus has worked in a lot of other countries. It had a long run in Sweden, of all places, and it has been done a lot in Pakistan and in India, where the theme of prejudice was adapted to the caste system. It was quite astonishing that it hit nerves there as well. But there's bullying everywhere. I've got a couple of grandchildren and it's a great problem in schools now. Sus is really a super-bullying story, isn't it?

It's been done in Los Angeles and New York [in 2001], where the reactions from black audiences were exactly the same as the ones we got in London. It's a funny thing, sometimes, especially with theatre writing, if it's set in a specific place, it then takes on reverberations wherever it goes. Like Tennessee Williams's plays - they're set in hot, sweaty New Orleans, but I saw a production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in Moscow in the snow and somehow it worked.

It's been done in Los Angeles and New York [in 2001], where the reactions from black audiences were exactly the same as the ones we got in London. It's a funny thing, sometimes, especially with theatre writing, if it's set in a specific place, it then takes on reverberations wherever it goes. Like Tennessee Williams's plays - they're set in hot, sweaty New Orleans, but I saw a production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in Moscow in the snow and somehow it worked.

It's a remarkable coincidence that Sus is also being revived on stage this spring. How did that come about?

The director, Gbolahan Obisesan, won the Jerwood Prize which involves funding for a production of his choice. And he chose Sus. It had a week's run at the Young Vic last summer and proved an enormous success there and so David Lan [the Young Vic's Artistic Director] decided to bring it back. It goes on a national tour before it arrives back there, including - I've just noticed - two nights in mid-May in Barking where Nick Griffin [of the British National Party] could by then be the MP. That would be an exciting night!

Indeed. What social changes have you observed in London over the last three decades?

The Long Good Friday was obviously about the transformation of the East End. The Bob Hoskins character was talking about the end of the Docks and mile after mile of territory for "profitable progress" - I think that was his phrase. I saw the film again about five years ago and it has a scene showing this model of how the area would look under the developers. It underestimated it completely - it ought to have shown Canary Wharf looking like Manhattan. Looking at it, I was taken by the fact that none of us had foreseen the enormous scale of change. Well, I certainly hadn't!

Those are the spectacular and the grand changes in the East End. But, just on the streets, everything is so much lovelier. I remember going to Paris for the first time years ago and wishing East London could have that kind of café life. Today there are a lot of smashing places and, with the greenery, the parks, Bethnal Green is beautiful on a sunny day. I know there are still dangerous areas, like Hackney's Murder Mile, but generally it's a really thriving and exciting place. That sounds patronising, doesn't it? But I mean it sincerely.

Do you think cinema has accurately caught that?

Do you think cinema has accurately caught that?

I very much liked A Kid for Two Farthings [Carol Reed's 1955 comedic fantasy based on the novel by Wolf Mankowitz], but people making films today are a bit behind the times - they haven't caught up with how different the area is now.

Do you feel that The Long Good Friday was responsible for the never-ending wave of inferior East End gangster films? At least Guy Ritchie seems to be moving on...

Yes, I liked Guy Ritchie as a director but didn't terribly like his writing. But one of the best films I've seen recently was his Sherlock Holmes which I thought was magnificent.

But other people are still churning out awful mockney movies like Dead Man Running..

[Dryly] Well, certainly there's a sense of déjà vu seeing some of those other films that came afterwards. I don't think the cinema has yet caught up with how the East End is nowadays and that's something I'm interested in doing, having dealt with the past. I'm thinking of writing something as we speak.

This would be your first film script since The Long Good Friday?

I've written another couple of films since then that haven't been made yet. Sus is coming out now and it's been 30 years since The Long Good Friday - I just hope it's not going to be another 30 years before the next one.

Watch the final scene of The Long Good Friday

The Long Good Friday itself seems ripe for a remake and/or a sequel...

There may be a remake set in Miami and directed by Paul WS Anderson, who made Alien vs Predator. It fills me with absolute loathing and wouldn't have much to do with what I've written. But I did write a sequel, called Black Easter Monday. It was set 20 years on and the Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren characters were still around - Harold comes back to East London to rescue it from the Yardies, having been in Jamaica where he took his retirement.

You remember that, at the end of The Long Good Friday he's in a car with a gun held at his head by Pierce Brosnan? [Watch this justly celebrated scene above.] How to get him out, that was my problem. Well, what I did was this: with all the bombings going on at the time in the film, there are road blocks in the Strand when he comes out of the Savoy and the car is stopped by the police. The gunman has to put away the gun and Harold gets out the car and says, "This is like a fucking Irish joke - goodbye!" That's the beginning of my sequel. But it was hard to get Bob Hoskins, Helen Mirren and Pierce Brosnan all available at the same time and it never happened. I think the moment's passed now.

All the same, it would be most intriguing to see an updated sequel set during the run-up to the 2012 Olympics...

There is some talk about this, yes. But The Long Good Friday itself nearly didn't get released. The Lew Grade Organisation, which financed it, hated it because they thought it was IRA propaganda. And then they said they couldn't show it in their cinemas because they were afraid that the IRA would blow them up. I asked someone in the Organisation why the IRA would want to do that if the film was IRA propaganda and he said, "Don't get fucking intellectual with me!" So, I always wait and see if these things actually happen. Keep travelling on optimistically. I think you'll find that anyone working in films has to be optimistic all the time.

- Check out the official website of the East End Film Festival, which starts tomorrow. The world premiere of the film of Sus plays on Saturday, 24 April. Following the screening there will be a panel discussion with the cast, crew and guests including Doreen Lawrence, Stephen Kamlish QC, David Akinsanya, Pennie Quinton and Shami Chakrabarti

- A national tour of a new stage production of Sus starts in Lincoln on 28 April and ends at the Young Vic (8-26 June)

- Find The Long Good Friday on Amazon

Comments

...

I see in the fear-year that