Thamar/ Sheherazade, Les Saisons Russes, London Coliseum | reviews, news & interviews

Thamar/ Sheherazade, Les Saisons Russes, London Coliseum

Thamar/ Sheherazade, Les Saisons Russes, London Coliseum

So-called Diaghilev tributes show a signal failure of taste in the producers

We’ve been so well educated or so roundly brainwashed to expect a certain high standard of Russian ballet that to experience the first two programmes of the three offered by the “Russian Seasons" team at the Coliseum, so-called tributes to Diaghilev, is more than a shock - it’s a brain injury.

While one would like very much to support the producer, Andris Liepa, in his laudable wish to reacquaint the world, and Russia in particular, with the sights and sounds of the 1909-12 seasons with which the Russian émigré Sergei Diaghilev shook the Western cultural universe, the shoddy production and performance standards subvert the enterprise wholesale. I thought The Blue God on the first programme might have been the nadir of any ballet production I’ve ever seen - the fleshy, posturing Nikolai Tsiskaridze a parody of his young self, not to mention a positive caricature of the young Nijinsky, a talent so dazzling that Diaghilev sought choreographers to turn him into a deity. And then last night I saw Thamar, once a short, irresistibly perfumed vehicle for Diaghilev's enchantress Tamara Karsavina, and this was truly a nadir of nadirs.

What both ballets have in common is that they are empty husks, wrappings whose contents have shrivelled to dust. Their choreography, originally by Fokine in both cases, has long vanished. Nothing of any value remains in them from the Diaghilev era except the evocations of their eye-blasting set designs, originally by Leon Bakst. The designs are the real motivation for the Liepa project, I suspect, dutifully and luxuriously recreated by a young pair of set painters, but so hideously lit by rock-arena lasers, spots, disco lights, that any shred of the atmosphere intended by Bakst ran away in horror. It’s a signal failure of taste in the producers that they have been so insensitive.

Even the music - which unarguably exists, written down, available - has been bowdlerised. For The Blue God, the score, originally in French 19th-century style by Reynaldo Hahn, has been replaced by the copious ejaculations of Alexandr Scriabin (admirable in various arenas, but not intended to be hauled into this particular usage). Thamar too has been doubled in length by adding more Balakirev to the original 20-odd minutes of his symphonic poem, fatally weakening the already slender story, and ruining any possibility of taking a short, intense pillule of insanely erotic orientalism. Instead, last night one had a ruinously long time to contemplate the pile-up of lost intentions and mislaid reputations, and the deep, deep disappointment of a sophisticated audience watching something like an extended lap-dancing act by a once-reputable ballerina now sheathed in a pink leopard-spot body with rhinestones over her tits and a lime-green laser light show bobbling around her.

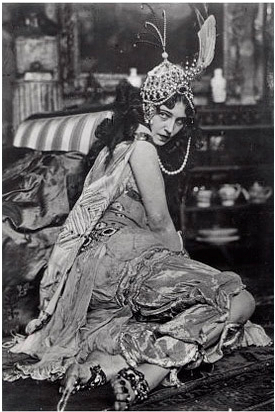

Each of the three programmes couples a “known” familiar with a “new” version by a modern choreographer of one of the legendary lost Diaghilev vehicles for his stars. The Blue God, which here played with The Firebird, was a creation for Nijinsky; Thamar was a smash hit for the exquisite Tamara Karsavina, made up with a beetling unibrow as a lethal goddess who slays when she seduces (pictured right, Karsavina as Thamar, 1912, photo Bert, V&A Collection). Balakirev’s lush, translucent music has many presentiments of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade, composed a decade or so later, and as both were originally Bakst productions, so one can see the arguments stacking up in factual minds for pairing them - though it’s too boring, I say, to have two pieces of such similar orientalist erotica in one night.

Each of the three programmes couples a “known” familiar with a “new” version by a modern choreographer of one of the legendary lost Diaghilev vehicles for his stars. The Blue God, which here played with The Firebird, was a creation for Nijinsky; Thamar was a smash hit for the exquisite Tamara Karsavina, made up with a beetling unibrow as a lethal goddess who slays when she seduces (pictured right, Karsavina as Thamar, 1912, photo Bert, V&A Collection). Balakirev’s lush, translucent music has many presentiments of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade, composed a decade or so later, and as both were originally Bakst productions, so one can see the arguments stacking up in factual minds for pairing them - though it’s too boring, I say, to have two pieces of such similar orientalist erotica in one night.

But Jurijus Smoriginas, who has “created” the new Thamar for Liepa’s enterprise, would not have made it past a single phrase of choreography before the impresario waved his spiritless clichés of wiggle-bum-and-high-kick away. Given that, and the almost comical caricature of Russian old-style gesture-mime that an unwise Wayne Eagling supplied for The Blue God, it would be too much for today’s performers to live up to the charisma and myth that surrounds those stars of a century ago. An out-of-condition, overweight Tsiskaridze, puffing like a grampus after the smallest jump, can bear no scrutiny as a messenger even of his own former lustre, let alone as a medium channelling Diaghilev’s young god.

Saddled with ludicrous, camp new choreography for The Blue God and ludicrous, camp old choreography in Sheherazade, Tsiskaridze grinned unstintingly at the audience and mugged like a vaudevillian for applause. Somehow, contrarily, this had a certain charm when he did it in a 19th-century classical warhorse of known properties, like Le corsaire as on last summer’s Bolshoi tour; but in Sheherazade this kind of sending-up goes against the grain of the music, which takes its story seriously, chugging with Eastern promise, lavish lust, alarm, fright, sweet wistfulness and a told-you-so finish.

I was talking afterwards with someone about my anger at what I saw last night, the travesty of Russian ballet’s proud technical standards (the Kremlin Ballet are not a distinguished company), Tsiskaridze's paunch, the (surely) misrepresenting of the calculated sybaritism of the Ballets Russes’s orientalist style by the trashing of the lighting and choreography. He pointed out that it is not necessarily helpful to have seen Altynai Asylmuratova or Uliana Lopatkina in Sheherazade, or to have a memory of Irma Nioradze long ago as a wild Firebird, rather than as the risible Thamar of last night. If you’ve seen fabulous, you’re in danger of missing the fun of the hokey nightclub awfulness of this performance. Or so he said. Maybe, but I felt just awfully sad.

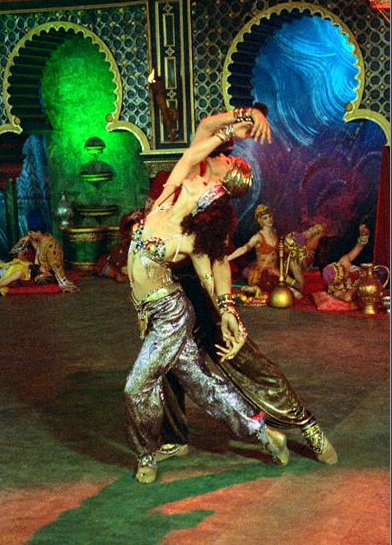

(Pictured below, the original Zobeide, Ida Rubinstein, in 1910, and Ilze Liepa a century later.)

There are a few good points: the St Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra plays reasonably well, even though their conductor, Alexander Titov, is one of those chaps who likes a loud, sturdy beat (this wasn’t best news in earlier sections of Stravinsky’s Firebird the other night).

There are a few good points: the St Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra plays reasonably well, even though their conductor, Alexander Titov, is one of those chaps who likes a loud, sturdy beat (this wasn’t best news in earlier sections of Stravinsky’s Firebird the other night).

The set painters, Anna and Anatoly Nezhny, deserve bouquets for their efforts to restore faithfully to the stage the extravagant set cloths and the incredible textile boldness of the costumes. Bakst was a Primitive colourist of vastly subtle effects - when he slammed bright pink next to scarlet, mustard, white and black, surrounded by aquamarine, he knew exactly what he was doing to the visual senses by altering pattern, cut and jewelling. It must have been an education to work on restoring those costumes. Just as it must have hurt them to see what the lighting crew did with their work.

- Les Saisons Russes du XXI Siècle show this programme again tonight, and Le pavillon d'Armide/ Bolero/ L'après-midi d'un faune tomorrow and Sunday at the London Coliseum

Listen to Balakirev's symphonic poem, Thamar, conducted by Yevgeny Svetlanov

Share this article

more Dance

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Add comment