Rhapsody/Tetractys/Gloria, The Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Rhapsody/Tetractys/Gloria, The Royal Ballet

Rhapsody/Tetractys/Gloria, The Royal Ballet

McGregor's too thinky, MacMillan too tame; Ashton and McRae are the name of the game

Is it odd that, in a bill containing an achingly contemporary première and a classic meditation on the First World War, a pastel-painted present for the Queen Mother’s birthday should race away with the honours?

Not if it was by Frederick Ashton, the Royal Ballet’s founder-choreographer. He’s been rather an undersung genius since his death, but maybe last night will tip the balance towards him again in the capacity crowd stakes, for his plotless Rhapsody (1980) was the standout piece in the Royal Ballet’s latest triple bill. Much of the credit goes to Steven McRae, who danced his heart out as the virtuoso male lead, giving us Baryshnikov-worthy split barrel turns (the kind of jump that provokes a visceral fear of broken ankles), insanely fast spinning chainés, and a crackingly Puckish smile, all responding to the percussive, Russian urgency given by Rachmaninov to the Paganini theme of his Rhapsody (the piano played by Robert Clark). To match McRae, we get the commanding Laura Morera, whose strong body the caprice theme ripples through, but never overpowers. Ashton’s constant changing of arm positions make the six supporting couples look more like twelve, as they beat their feet, and try to keep their arms Ashton-willowy at great speed (Elizabeth Harrod managed beautifully). It’s tremendous stuff from all concerned.

The only surprise about the next piece, a collaboration between Wayne McGregor and visual artist Tauba Auerbach, is that it didn’t happen sooner. McGregor, known for his fascination with deconstructing both movement and the creative process, and Auerbach, equally interested in disrupting conventional constructions of visual meaning, clearly have a great deal to say to each other. Add JS Bach’s enigmatic last work, The Art of Fugue, into the mix, and there are - as always with McGregor - many levels on which the new work premièred last night, the unwieldily titled Tetractys - The Art of Fugue, could be fascinating.

The only surprise about the next piece, a collaboration between Wayne McGregor and visual artist Tauba Auerbach, is that it didn’t happen sooner. McGregor, known for his fascination with deconstructing both movement and the creative process, and Auerbach, equally interested in disrupting conventional constructions of visual meaning, clearly have a great deal to say to each other. Add JS Bach’s enigmatic last work, The Art of Fugue, into the mix, and there are - as always with McGregor - many levels on which the new work premièred last night, the unwieldily titled Tetractys - The Art of Fugue, could be fascinating.

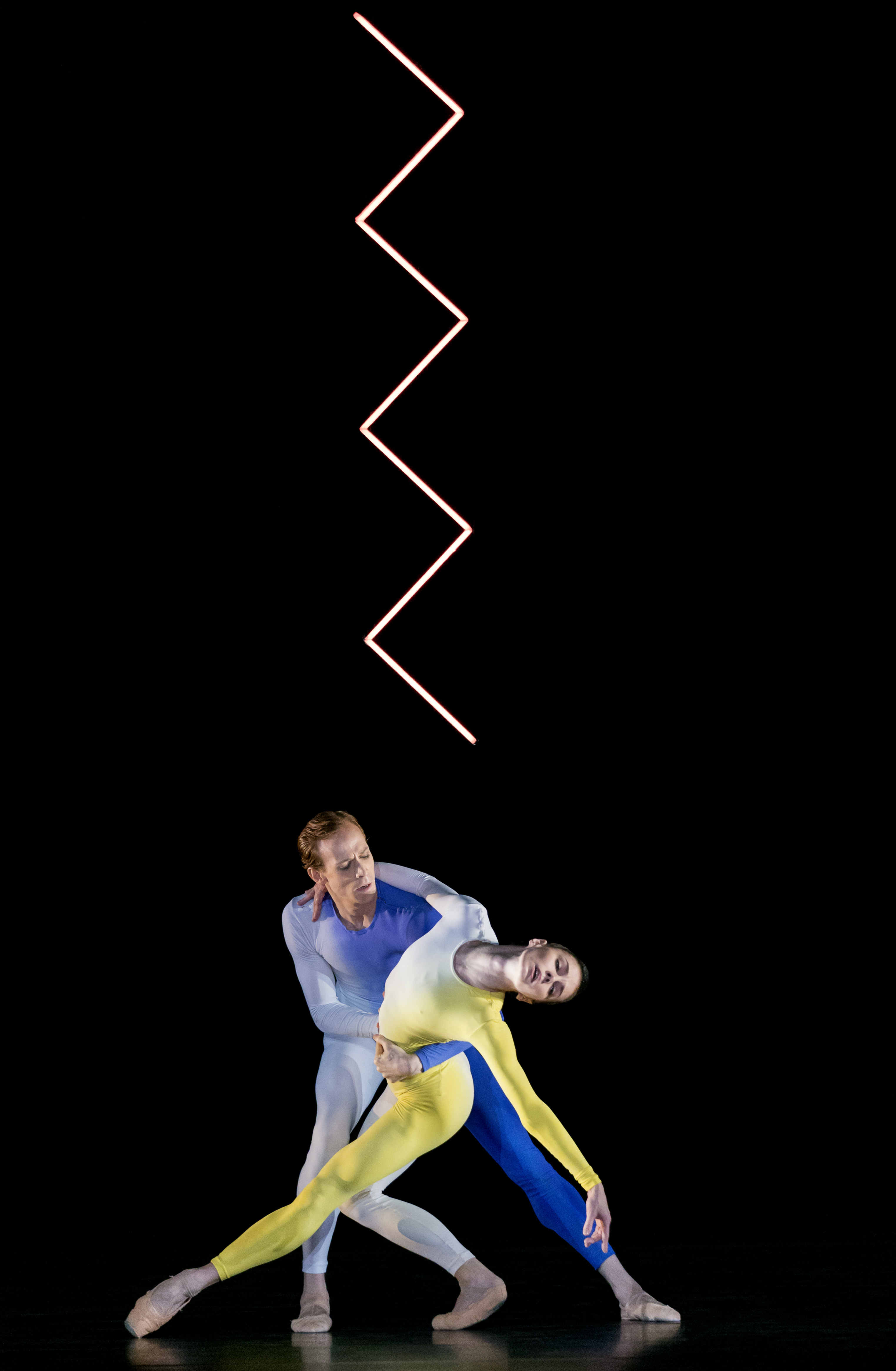

Unfortunately, as with most of the new McGregor I’ve seen in the last couple of years, Tetractys was probably far more fascinating to make than it is to watch. On a mostly black stage, varying configurations of dancers duet, trio and sextet with each other, their patterning related to the complex geometry of the music. Behind and above and to the side, Auerbach’s striking light scuptures make line-based glyphs that are “scaled, sheered, inverted, expanded and ornamented” in accordance with the changes in the fugue subject over seven movements (Fugues 1, 4-6, 13-14; Canons 1 and 4). Changes in the colour of both glyphs and costumes (predictable primaries give way to honeycomb, custard, parma violet and azure) cipher changes in the music’s tonality and construction. Twelve dancers must twist and stretch themselves through McGregor’s kinetic choreography to bring this elaborate 3D fugue to life for 40 whole minutes (at least 10 too many in my book). Yes, it’s thoughtful and careful and must have been a hell of a lot of work. It’s just cold, cold, cold.

You don’t put eight Royal Ballet principals on stage without getting some charisma, and so the best moments of Tetractys come courtesy of its stars: Ed Watson and Natalia Osipova (pictured above right) sinuous to the point of unsettling contortion; Thiago Soares and Eric Underwood holding Marianela Nuñez so that just one pointe shoe taps the ground – from above her head in a drastic fish dive; the chunky gravitational presence of Paul Kay unbalancing Sarah Lamb and Stephen McRae’s stark monochrome duet. But we’re missing the pulsing urgency of Chroma, the strange poignancy of Infra, or even the trust in Bach himself that would allow the music to draw us – helped by Auerbach’s hypnotic glyphs, which I did very much like – onto another plane.

You don’t put eight Royal Ballet principals on stage without getting some charisma, and so the best moments of Tetractys come courtesy of its stars: Ed Watson and Natalia Osipova (pictured above right) sinuous to the point of unsettling contortion; Thiago Soares and Eric Underwood holding Marianela Nuñez so that just one pointe shoe taps the ground – from above her head in a drastic fish dive; the chunky gravitational presence of Paul Kay unbalancing Sarah Lamb and Stephen McRae’s stark monochrome duet. But we’re missing the pulsing urgency of Chroma, the strange poignancy of Infra, or even the trust in Bach himself that would allow the music to draw us – helped by Auerbach’s hypnotic glyphs, which I did very much like – onto another plane.

Contrast then the third piece, Kenneth MacMillan’s Gloria (1980), which is painted in rich colours by Poulenc’s Gloria, (credit to conductor Barry Wordsworth, the rich and spiky Royal Opera Chorus, and soprano Dušica Bijelic). The dancing in this semi-abstract meditation on the trauma of the First World War is surprisingly peaceful for MacMillan, the master of character and psychological darkness. The most powerful figures are not, as in Mayerling or The Judas Tree, the name-able people contorted with real emotions, but white-clad anonymities with their backs turned, just sitting, staring into an abyss that we cannot see. Among the soloists, Thiago Soares (pictured above left, with Sarah Lamb) stands out for embodying nobility and anguish with just the abstraction needed to suggest the horror of the general sacrifice in which an entire generation was lost, and Meaghan Grace Hinkis caught my eye leading the pas de quatre. It is a strong ensemble cast, including Sarah Lamb and Carlos Acosta, as well as several promising young soloists - but this Ashton-McGregor-MacMillan journey has been a long one for both dancers and audience. No surprise then to feel a little muted at the end.

- The Royal Ballet's Rhapsody programme is at the Royal Opera House until 15 February

rating

Share this article

more Dance

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Giselle, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - if you go down to the woods today, beware of the Wilis

A revival of Mary Skeaping's lovingly researched production, packed with lively detail and terrific suspense

Giselle, English National Ballet, Coliseum review - if you go down to the woods today, beware of the Wilis

A revival of Mary Skeaping's lovingly researched production, packed with lively detail and terrific suspense

Add comment