Q&A Special: Choreographer Slava Samodurov | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Choreographer Slava Samodurov

Q&A Special: Choreographer Slava Samodurov

The strangely easy change of life from a top dancer to a gifted new choreographer

Choreography is a mystery art. How it happens - or indeed what happens - is as elusive to define as pinning down a brainstorm. There is no solid stuff, no rules, no pre-formed maxims, everything moves; the choreographer goes into a studio, finds some dancers, finds some music, finds some moves, finds some light and atmosphere - and this agglomeration of variables goes out on stage all too often to fall flat, a soufflé that didn't rise. It was insufficiently skilled, or its ingredients were stale, or it lacked the leavening of a compelling imagination or the flavour of real emotional imperative. But what is going on?

Some choreographers, like William Forsythe or Pina Bausch, are consummate editors of their disciples' ideas; some, like Frederick Ashton, snap up abilities, nuances, accidents, from the dancers in front of them; others, like Ninette de Valois and Martha Graham, ordered the dancers to do what they had already imagined. Can such a thing be learned? Most ballet choreographers of any merit get the bug at school and work their way gradually up a ladder from elementary pieces for their classmates to the big stage. They are not supposed to spring virtually fully formed into the limelight, with a considerable talent attached. That, though, seems to be the uncommon case with the Royal Ballet principal man, Vyacheslav Samodurov.

Two years ago Samodurov was still dancing classical and romantic leads on stage at Covent Garden, but knee injury was dragging him down. With 30 well behind him, and with a life as a peripatetic Russian, he was in the turbulent age when a change of direction might be looming - it is much harder for a thirtysomething dancer to recover from major injury and get back his top spots.

Two years ago Samodurov was still dancing classical and romantic leads on stage at Covent Garden, but knee injury was dragging him down. With 30 well behind him, and with a life as a peripatetic Russian, he was in the turbulent age when a change of direction might be looming - it is much harder for a thirtysomething dancer to recover from major injury and get back his top spots.

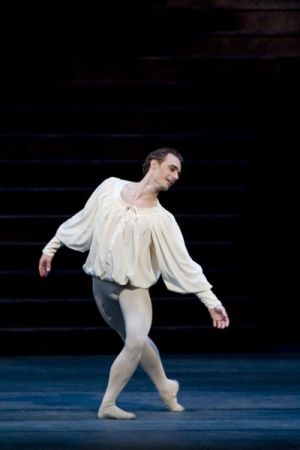

Samodurov burst into my view at Dutch National Ballet in a performance of Balanchine's Rubies, where he struck me as a man of secrets, a jester with an inner fibre of melancholy - that is, a performer capable of sounding two messages at once, and a rare animal in ballet. On joining the Royal Ballet in 2003, he shone in interesting, off-kilter roles, the Nijinsky Faune, Satan in de Valois's Job, MacMillan's Lescaut (the sinister, dual-natured brother of Manon), a witty muscleman in Nijinska's Les Biches, but he also brought great individuality to MacMillan's Romeo, a lad with a split in his instincts between laddishness and concealed romanticism. But we never quite had a finishing performance from him, and kept hoping the knee would recover.

At this stage many a leading male performer has attempted to leap into choreography, from Adam Cooper to Irek Mukhamedov, but those stellar performers now know only too well that knowing your craft superlatively as a dancer gives no assurance whatever that you have the creative X-factor.

However, that Samodurov possesses something special was swiftly evident in his first tentative little workshop pieces a year or two ago, and it was eloquently confirmed last month with his new Royal Ballet studio piece, Trip Trac (above, Melissa Hamilton and Valeri Hristov, photographed by Andrej Uspenski/Royal Ballet), using Shostakovich for choreography of such accomplishment that it won plaudits across the board.

Tomorrow Samodurov’s talent is seen on an even larger stage at the London Coliseum, with the unveiling of his new ballet for the Mikhailovsky Ballet, St Petersburg’s second company.

Slava (as he is now known) Samodurov was understandably wired with excitement and tension when we met inside the Royal Opera House and discussed this high-profile turn to what has already been a high-profile performing career.

Above: portrait of Slava the choreographer by Charlotte MacMillan. Below: Slava the dancer, rehearsing Balanchine's Stravinsky Violin Concerto with Alexandra Ansanelli, photographed by Johan Persson

ISMENE BROWN: So you are now a choreographer?

SLAVA SAMODUROV: I am. I am very happy about this transition!

It’s so quick. Two years ago you said in interviews you weren’t going to be a choreographer.

I know, but it was always in the back of my mind. Yes, two years isn’t a long term for someone to become a choreographer. Luckily I had the time to concentrate on this transition.

Tell me the steps whereby you made that change - usually one would expect there to be some academic training for choreography, most of them start in school. You’ve learned on the job, as it were, so what were the key steps for you?

Difficult to pin down, but I had a modest experience when I was younger in Russia, which didn’t really lead anywhere. This was in St Petersburg at the Mariinsky, when I had to choreograph a couple of times for myself for galas. I had to do perhaps three pieces, one to be contemporary and I didn’t have any, so I thought I’d do something for myself.

I’m presuming that choreography needs lessons of some kind. Can it be taught?

I doubt it. I really don’t think so. If you compare it with composing, choreography is not as scientific, not so far. Music has laws and knowledge - I guess choreography has laws but they haven’t been set formally. it’s a more unstable and free creative act.

And presumably more dependent on your own experience, and how you put that into your imagination.

I think it is a fairly subconcious art really. Maybe in future there will be laws and methods found to help people create.

I suppose one big challenge is that usually choreography doesn’t happen until you are in the studio with certain dancers.

That’s the truth. Plus I think the other big challenge actually is how to write it down. I am taking time to get my head around that. I don’t want to commit to full and complicated studies of Laban notation or something, but there is definitely a necessity to write it down. Video is not enough - every night people make mistakes, or they interpret things. Which is fine for performance, but the next generation should not learn it from someone else’s interpretation. What’s beautiful about music or words is that you can actually write it down as a pure text and it simply exists.

You know Marie Rambert said in around 1910 I think that all dancers should have to learn to read and write dance notation, just as musicians learn from scores, so that there should always be a pure text in itself.

There’s a lot of truth in it. Whereas in Russia the repertoire is constantly repeated, so it feels as if it is being preserved by constant repetition, in London something can disappear for a few years, and the company may change - so there is more necessity to write it down.

How many ballets have you made in two years?

Three for the Royal, probably five ballets of different length, and I made my sixth one for the Mikhailovsky.

How do you approach the difference between choreographing for a big stage like the Mikhailovsky’s, which will be performed in the Coliseum, and the smaller Linbury studio stage? Is there consciously a need for more action, more running, mor leaps, more of a floor plan to cover the space?

I think for the Linbury, yes, I was conscious the space is small, but in a way you can have more intensity in the steps as a result. At the same time I try not to put all my rocks in one box - I have to think that the choreography should work in different spaces.

Has becoming a choreographer changed your outlook to life?

Yes, but I am only starting my journey. I feel my life has a second breath, a second start.

Because it’s a nervous time when a dancer reaches mid-thirities and has an injury. What happens next?

Yes, everyone faces this anxiety, but in my case it was actually a natural transition, so quick that I almost felt I didn’t have to make a choice. Probably I had already made my mental departure from performance before I stopped dancing.

I don’t want to spoil my own pleasure in your Royal Ballet piece last month by telling you what I made of it. You probably have completely different ideas to what I saw. Yet to me there seemed to be some very clear almost biographical material: it was very personal about what you have danced, there seemed to me to be Balanchine, Forsythe, Royal, and a bit of Dutch influence. I felt that this was a ballet with a personality, of yours, and I wondered if you had actually done that - or I’m imagining it.

No, you’re right. I called it “dance movements” because it was a conscious choice to make them different. I was actually very surprised by your criticism because I felt you had got me 100 percent right. Though I didn’t think it was that clear on the firs tnight it came out more clearly on the second and third night. So... I was nicely surprised that somebody could nail it completely like that.

Do you always hope that the spectator sees exactly what you intended? Or are you happy to have them see what they wish to see? You are quite a precise person, I think, so I imagine that you would prefer to be read as you intended...

Yes, but at the same time I needed to think about the concept of the ballet - you can’t expect the spectator to know that much about ballet to get this, so I hoped mainly that for those people this should be entertaining at least.  Who have you found most helpful at the RB in developing your language, or have you done it on your own?

Who have you found most helpful at the RB in developing your language, or have you done it on your own?

Not so much in language, but I’ve really appreciated the support of Wayne McGregor. It is the help he gives you to believe in yourself, and have the courage to create things.

What do choreographers talk about? On the face of it there’s little in common between your choreography and Wayne’s.

We don’t talk about choreography, though I really value his opinion a lot, as well as Monica’s [Mason, Royal Ballet artistic director]. But it’s more about what to do in difficult situations... dancers, or changes of roles, or this couple is not quite working and maybe it wasn’t the right choice. Yet you don’t want to disappoint them! So it’s a lot of problems, small and large, which can be quite crucial.

You have the advantage over younger choreographers like Liam Scarlett - I remember [former Royal Ballet choreographer] Matthew Hart telling me when he was making Dances With Death in 1996 it was quite scary for a 20-year-old to tell a principal like Darcey Bussell what to do. But you have an authority in the company already as a dancer - I imagine you have no fear of that.

Actually I find being a choreographer is much more stressful than being a dancer. I feel very vulnerable sometimes. That’s why I say I’ve started my departure. The more works I make the more the distance I feel between me as a dancer and me as a choreographer set apart from the dancers. I’m the other side of the room now, I’m sitting on the chair, I’m looking at them, I am no longer with them. It’s a transition. And as every dancer is an emotional person it’s a matter of learning psychology, what you have to take into account, what you have to ignore.

Balanchine didn’t bother much with psychology!

By the end, probably yes, when he was recognised as the master. But I bet at the beginning he had a lot of problems and was really careful. But it looks like I have a good response from dancers.

It doesn’t always work for choreographers that they manage to put a personal mark on what they do. But when you deal with dancers, do you feel ready to look into their eyes and draw something out of them there and then to make a mark? Because de Valois came into the studio with her whole thing planned; Ashton and MacMillan did it on the hoof. Are you an instant man, or are you someone with strong plans in advance?

Somewhere in the middle. I find it’s more and more interesting though to create in the studio working with the dancers.

Do you move pieces around the table to make patterns?

No. I draw things. But we don’t really have the luxury of time. If you go to the studio and don’t know what you’re going to do and hope for luck, and then make nothing - well, too bad, you’ve missed a precious session. I can’t afford that. In a way, it’s about being a professional - some days you can create something spontaneously right on the spot, others you have to use a prepared idea.

Do you wake up in the middle of the night with an idea?

Sometimes it’s that. Or it’s thinking, thinking, thinking, and something comes along. Bach, Handel, they could write at the click of a finger. They didn’t wait for the big inspiration, they were professionals.

I think MacMillan said to Christopher Wheeldon when he was 15: “Practise.” You being a photographer as well, you have a way of searching a dancer you’re photographing and trying to create personal images for each one - is there any similarity in choreographing with them?

Not quite, but I think photography has been a big help for me. It made me look more at the world of contemporary art, and though I don’t know exactly how, I think it’s shaped the way I think, that ballet should be part of the contemporary art world.

Does that means it’s more external - you use your eyes to observe things and put them into the material? Or are you more introspective, the way MacMillan was, looking inwards? I mean, I don’t want to put you into a box, but as a performer you always seemed to me to have a powerful inward quality in your performance.

I think it’s a two-way stream - you look out to see, but then you burn it inside yourself, and you come up with something that you hope is creation. You can’t always be the starting point of each creation. I find myself maybe like a volcano - I bubble for a while, then I need to accumulate energy - it could be a movie, a good light in the street, a nice day, a book. Right now I’m on a quest, and I know exactly what I’m looking for . It’s a new commission?

It’s a new commission?

It’s early days, but I’m thinking of preparing an evening of my work to take to Moscow and St Petersburg with Royal Ballet dancers. I know what the programme is.

My god, you must be confident.

I don’t know, maybe I’m foolhardy. But I do have a concept of the evening.

You’re excited by the prospect?

Very much so. I thought I need to do it, it will be important and interesting for me as a choreographer - once you do a ballet here, and another ballet there, it’s easy to repeat yourself, and it worried me when I was choosing music for my Opera House work. I was trying to choose music that would stretch me, would challenge me. And if I were to put three of my ballets together I could not repeat myself.

You as a dancer have not that often worked with choreographers in new creations. You worked with Alexei Ratmansky in St Petersburg in the Kirov though.

Yes, it was in the late 1990s when he made his first evening of his ballets for the Kirov.

You’ve continued contact?

Yes, he is the person who started my choreographic career really, because he called me and asked if I’d like to do something for the Bolshoi choreographic workshop, and I said yes! It was around 2007. I chose Ekaterina Krysanova and Andrei Merkuriev for a 10-minute duet. The work had a very good response there, I showed it to Monica, and she said, “You must choreograph for us.”

Which other choreographers did you work with as a dancer? Obviously in Holland when you were with Dutch National Ballet.

Hans van Manen, Rudi van Dantzig, Wayne Eagling, David Dawson. It didn’t happen often, but I really enjoyed it.

So as a dancer, what did you feel choreographers wanted from you? Now that you are a choreographer working with dancers, are there things now you wish you’d known then when you were the dancer in the relationship?

Millions of things.

What makes dancers interesting to choreographers?

Difficult to say - sometimes it’s personality, sometimes certain abilities. There are certainly some dancers I find very stimulating to work with. it’s probably the way they move. Then there are excellent dancers who I just don’t know what to do with. Maybe they do my steps in a way that I don’t expect and it doesn’t work for me.

Is it relevant that they are your friends?

No, it’s not important. I suppose I do prefer work with my friends, it’s more comfortable psychologically in the studio. But as I say, more and more I look on dancers as material, and my friendship moves aside.

One of these days either your friend is going to let you down - or you are going to say to a friend as a choreographer, sorry but...

It hasn’t happened quite like that yet. I’m still learning, sometimes I do make casting mistakes, but it’s part of experience.

Have you been able to correct the mistake and get someone else without causing a big row - or at the moment do you just live with the mistake?

Until now, I would keep quiet and make the best of it. But now I’m more likely to change the person for the sake of the choreography. I imagine it happens all the time. There was an occasion when MacMillan wanted Manon with Darcey and Irek, but the heights were wrong, and he replaced her with Viviana. I suppose there are times when we respect the work of people we don’t like, and can’t work with people we really do like.

I imagine it happens all the time. There was an occasion when MacMillan wanted Manon with Darcey and Irek, but the heights were wrong, and he replaced her with Viviana. I suppose there are times when we respect the work of people we don’t like, and can’t work with people we really do like.

I have to say, I haven’t yet been in that situation yet. I have had 100 percent good experiences with friends and they haven’t let me down. I can say Mara Galeazzi is a very good friend and I love working with her - she has a very Italian temper and some days she’s very loud and goes, “Oh babe, but, but, but”, but I know there is always going to be quality produced, and I like her charisma. It’s just enjoyable.

And you’ve taken pictures of her too.

I think she’s an Artist, with a capital A.

As outsiders, we see the extraordinary relationship between choreographers and dancers can sometimes seem quite exploitative - in Jann Parry’s biography of MacMillan, Different Drummer, there’s a section about MacMillan not casting Lynn Seymour in something, yet she’d been such a close and supportive friend to him, and they had a long bust-up. And the rows between Balanchine and Farrell. You imagine that for a choreographer psychologically you have to move your mind into a completely new plane working with dancers.

I’m thinking about that a lot. It’s not that you don’t like that dancer, it’s just that for that particular project you need something different in the quality, like different music or different designs. It can’t be a formula. And sometimes it does hurt people. It’s the difference between being a professional colleagues and being friends.

Are you sociable or a loner?

Fifty-fifty. When I work intensely I don’t think I like much company. This company is a bit like travelling on the tube - a lot of people all around you but they’re all busy and you don’t have to interact. Everyone is on a quest of their own.

Let’s talk about your start in ballet. When were you born?

May 1974 in Tallinn.

Do you remember it much?

Not much. I didn’t really live much in Tallinn. We had moved near Moscow by then, and I was probably 8 or 9 when we moved to St Petersburg. My father was in the army, my mother’s a housewife, and I’m the only child.

Do you have a musical background?

No, but my uncle was a ballet dancer.

You started dancing when?

When I joined the Vaganova School I was about 10.

Because at that period Russian ballet was very physical and “Soviet”, dominated by Grigorovich, wasn’t it? That’s what we saw here on the tours anyway. So was the physicality of ballet the big draw for boys?

I don’t know. It was my mother who made me go into ballet. I was not that interested - I was doing figure-skating, but with out much success. I was training in a professional sports school and that had ballet class as part of the training, and there was a moment when you had to join the sports school and basically aim towards professional skating. My coaches said I probably wasn’t going to make it.

Were you a hard worker?

Yes, I think so. Working hard is nice. But when I joined the ballet, I did feel it was another kind of sport - as you say correctly, it was very physical. And it was also a lot of fun, going to the theatre, to see the Kirov Ballet, the Kirov Opera. I remember Altynai Asylmuratova, Faroukh Ruzimatov, Igor Zelensky - there were some excellent dancers.

That was a very high standard to watch. did that go into your head and change the way you thought of ballet - tell you that it wasn’t a sport?

I probably was very critical then, actually, maybe a little self-centred when i was young, so I didn’t really have an idol. But I did know what I wanted to achieve.

I think you sometimes just need an imaginative pull. Sometimes it is an idea. Baryshnikov said his home life was so unhappy that theatre felt holy, it was a place of comfort and inspiration, it felt like going to church.

I think I loved theatre generally, not just ballet.

Did you feel when you joined the Kirov that ballet was as satisfying a form of theatre as you’d hoped?

I felt very privileged indeed to work there. I was 10 years with the Mariinsky Theatre, and actually the novelty wears out, and in the end you look for other things - and there was a big gap between Mariinsky and Dutch repertory.

Did you consider Moscow and the Bolshoi?

No, it was even less interesting. In my first year in Amsterdam, 2000, I danced more ballets than I think I had in my whole career till then. In Holland I rediscovered my love for ballet. It was all about the choreography - I think it was a great company, and Wayne Eagling has a great sense of repertoire.

There was a TV documentary made about you in Holland?

Made by Russians, Four Days in Slava’s Life. They were more after my personality, really. There were things I was doing between Mariinsky and Dutch National Ballet, and they were trying to capture me in transition - I think they wanted to make an “art” movie, not a movie about a dancer. There were no words, no dialogue, not much about dance, just me in the different city centres and theatres.

So in Holland you did a lot of modern ballet, and somewhere along the line you still felt you needed to move on? Was it restlessness? What appealed about London and the Royal Ballet?

I found one big minus in Holland - it is not a ballet country. Despite having good dancers and two great companies, it is not a ballet country, which is quite a minus in the theatre.

What is so important about ballet rather than contemporary dance for you? Why does it upset you that a country that loves contemporary dance doesn’t value ballet?

Ballet is about quality, probably. Tradition, vocabulary, and appreciation and understanding of what is good and valuable and what is not. It is important for a company to have people around - whether society or fans - who can understand the difference between good and bad pirouettes, or good and bad productions of Swan Lake.  But what about people like Michael Clark who totally reuses classical ballet vocabulary - or Merce Cunningham whose vocabulary has nothing of ballet in its writing but is as disciplined and detailed as ballet? I imagine you as a choreographer have this entire range to work in, and it extends far beyond classical.

But what about people like Michael Clark who totally reuses classical ballet vocabulary - or Merce Cunningham whose vocabulary has nothing of ballet in its writing but is as disciplined and detailed as ballet? I imagine you as a choreographer have this entire range to work in, and it extends far beyond classical.

That’s why I said “quality”. Not all famous companies have good productions - sometimes they’re surprisingly bad but still the “quality” of dancing is there. Classical ballet doesn’t take liberties. I think here the Royal Ballet is an outstanding company and you can understand why it is so famous. The “qualities” here are far different and more varied than the Mariinsky’s, which is so much more homogeneous and comes from one school. But it’s also about the quality of the audience that has grown up on that quality that is being offered.

I remember when I was in Dutch National Ballet, I saw a general rehearsal by the Royal Ballet of Song of the Earth and The Dream here, and I thought it was absolutely wonderful, everything danced with such precision, beauty and elegance. And I couldn’t understand why the Bolshoi who were here at the same time were getting such great reviews here. Then I went to see them perform, and they didn’t dance with such precision but I saw such joy in their performance. You need to combine those things. No company has an absolute monopoly of all the qualities. When I go back to Russia after so many years in the Royal, I am surprised sometimes by how they do things. But then I understand that for Russians to see British dancers in their productions would be equally strange. It’s all about the context of taste. There are different definitions, that’s all. How can you say German musicians are better than French musicians?

I think it was Arlene Croce - you know they don’t like MacMillan’s work in America - who said about one of his pieces, even if it was a bad ballet it was a bad ballet by a good mind. I think the good mind is the key. I can see there are ballets I don’t like, but I know they’re good of their kind - it’s just not the kind of mind I relate to.

I think that is very well put, actually. I think if you’re talking about companies - and there aren’t so many of them in the world - none of them takes first place, it’s all down to subjective taste and the nature of that particular performance of the work.

Do you find you are now more in love with ballet as the result of the evolution of your career into choreography? Or do you think you might move away toward contemporary work, like Baryshnikov, Guillem, Maliphant?

If I stayed dancing I think my joy would definitely wear out, but now I am a choreographer it’s exciting to have a language that I think I’m hoping to develop, and it's a new world to juggle with.

Do you see yourself as London-based or still quite nomadic?

I do travel a lot, but I think now I really do appreciate London a lot as a crossroads for the world, in all sorts of ways. I can see I have so much access to art here.

Yet here you are about to show a premiere with the Mikhailovsky from your city, and you want to do a Russian evening. So it matters to you to impress your countrymen? There is a pull in your heart back to Russia to show them what you’ve done?

No, I think I’m being more calculating!

We English always have this idea that Russians always feel deep nostalgia for Russia.

Not really. I can go there any time and I do and of course there are many inspiring things. But in a way I almost feel Russia is behind in the choreographic sense at the moment. Of course Alexei [Ratmansky] is a really great choreographer, but I don’t think I can name anyone else at the moment.

Tell me about your Scarlatti piece for the Mikhailovsky, In a Minor Key, which is about to be performed in London.

It’s a selection of Scarlatti sonatas, played live by Alexander Pirozhenko.

How do you control how he plays it? Does he do it his way or do you ask him for certain tempi?

No, he is a specialist. I give him certain freedoms, but in a restricted sense. So I want him to bring himself into the performance, but obviously when I’d started the project I had already heard some recordings and had ideas on this account. I had heard some Ivo Pogorelich.

Very slow, I guess?

Yes, very different, but it had incredible feeling to it. Originally these were sonatas for harpsichord, which definitely has a different feeling from piano. So I asked Alexander for certain pieces to bring in that rather electric sound of the harpsichord - it’s something I’m playing with in the choreography, quite rough, almost an irritating sound some people find it! There’s a little trick in the way the sonatas are arranged and repeat material.

Below: Ivo Pogorelich plays Scarlatti's sonata K450:

Do you have to go into it thinking, this is a company ballet so I have to have pas de deux, pas de six, ensemble... I remember David Bintley saying if you do a company pieces sometimes you feel obliged to employ as many as possible.

Well, I talked with Misha Messerer (the Mikhailovsky’s artistic director] about this, and we decided to use a small cast of only six dancers. I think these are really outstanding dancers. It was a new experience for me to go into the studio and see dancers I did not know and who had no real encounters with modern choreography, then work with them. In that way I’m being not just a choreographer but a teacher, explaining how to approach this new choreography.

So it’s a learning curve.

Yes, which is why it also has a classical feel to it. It was a great chance for me to do a piece for a main stage in Russia. Is that a big thing for you - this is your home city, St Petersburg, with its iconic ballet tradition? Must be scarier than working in the studio at the Royal Opera House (pictured left as Romeo at the Royal Ballet by Johan Persson).

Is that a big thing for you - this is your home city, St Petersburg, with its iconic ballet tradition? Must be scarier than working in the studio at the Royal Opera House (pictured left as Romeo at the Royal Ballet by Johan Persson).

The Linbury isn't a studio, it's a stage. Anyway, it’s equally scary in both places. It’s always about the way you challenge yourself, and you’re always trying to grow. For me working with the Mikhailovsky Theatre is a challenge to make an independent work that can stand on its own. Here, in London maybe the ideas I used were more sophisticated, it’s a studio piece and it is giving me more ideas to work on.

What about Moscow now, under new management? Do you have any relationship with Bolshoi now that Ratmansky is not there? There was a flowering of creativity when he was there, it seemed.

I decided not to wait for anyone to ask me. Just to do the work. Like Wayne did.

Who will back your Russian evening?

It’s too early to talk about but it will be backed by the Ministry of Culture. Also I am looking for private patrons, so if you know anybody please put them in touch.

- The Mikhailovsky Ballet performs Samodurov's In a Minor Key on a triple bill tomorrow (Sunday) at the London Coliseum, and in Swan Lake (22-25 July), Cipollino, a children's ballet (today & 24), and Chabukiani's Laurencia (20 & 21 July)

- Charlotte MacMillan's website

- Johan Persson's website

Samodurov also found harpsichordist Scott Ross, below playing Scarlatti's sonata K209, inspiring to his choreographic imagination:

Share this article

more Dance

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Add comment