Opinion: Let's put a brake on this facile culture of 'celebration' | reviews, news & interviews

Opinion: Let's put a brake on this facile culture of 'celebration'

Opinion: Let's put a brake on this facile culture of 'celebration'

Art Everywhere is the latest heavily PR-ed project to get people enjoying culture, but 'celebration' is no substitute for critical enquiry

What happens when art is everywhere? Does it become wallpaper? Visual white noise?

So on what grounds could one sensibly object to this loudly PR-ed, demotic celebration of British art? That is, the art that's free to view in our national public collections but that few people other than tourists actually go to see? Hell, we should all celebrate it.

Little really, except that when we really engage with a work of art, what we don't do is facilely "celebrate" it. Indeed, that's a notion that sits uneasily with proper critical engagement, which is about getting under the skin of a thing by using our critical apparatus and a whole set of aesthetic values - which is frankly harder to do than going "oh, that's nice", just by glancing up at a giant reproduction on the way to somewhere else.

Little really, except that when we really engage with a work of art, what we don't do is facilely "celebrate" it. Indeed, that's a notion that sits uneasily with proper critical engagement, which is about getting under the skin of a thing by using our critical apparatus and a whole set of aesthetic values - which is frankly harder to do than going "oh, that's nice", just by glancing up at a giant reproduction on the way to somewhere else.

Here's the thing: critics, not known for championing popular opinion but rather scorning it, would normally find an artist such as JW Waterhouse, with his pallid water nymphs and vapid mermaids, "execrable", as Jonathan Jones, the art critic for The Guardian does (not used to exercising restraint in his reviews, Jones completely savaged the "execrable" Waterhouse when the Royal Academy held a survey of the Victorian artist a few years ago).

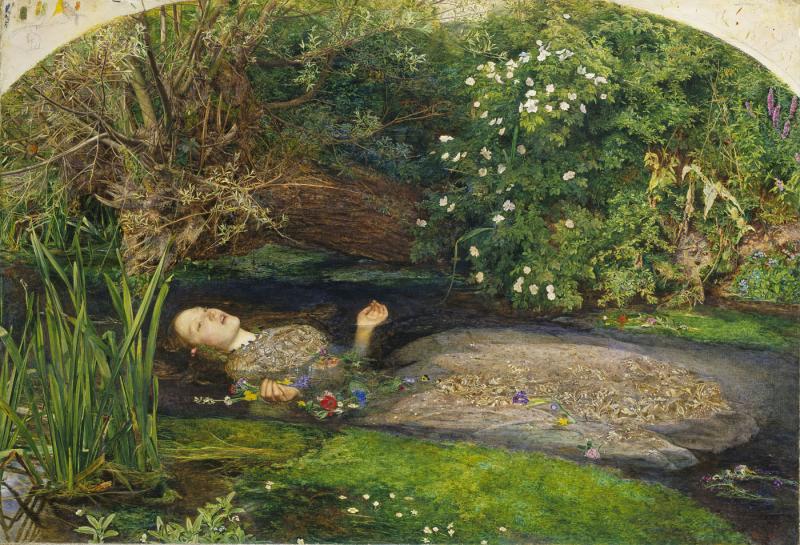

But the same voices appear to have greeted the blandly celebratory, glibly well-meaning and smoothie-promoting Art Everywhere with enthusiasm, including Jones, though he himself has written how mind-rottingly bad British painting was for about 100 years. He identifies Francis Bacon as the figure who got us out of the British art rut by moving away from stuffy English moralising and going heavy on French existentialism, while French art naturally went from strength to strength. But while Jones and others were writing about what a marvellous idea it was to put up facsimilies of the nation's favourite work on billboards, could it have been a surprise to anyone that Waterhouse's The Lady of Shalott might poll at number one, with Millais's Ophelia (main picture) coming a close second? They're just two of the artists most critics hate. (Luckily, Bacon creeps in at number three with his screaming pope.)

This isn't about being pointlessly snobbish (I have never had a bad word to say about either Waterhouse or Millais, two 19th-century painters whose work rises above that of most of their contemporaries - plus, it goes without saying that there are some really fantastic works of art on this particular list). But there's a wider issue here that Art Everywhere seems indicative of, and it's this: isn't this glib culture of "celebration" - celebrating art, celebrating books, celebrating figures and events in history (and all through the interminable popular list) mildly depressing? Just a little? It seems rather intellectually dishonest, for a start, as if art people were suddenly pretending that this was in any way a substitute for a real, intimate engagement. As if the exposure to posters will turn people into "art-lovers". Enquiry and critical interest have nothing to do with "celebrating". An intelligent visual culture will help you articulate why you think something is not very good, as well as why you think something is powerful, because we're not just mindlessly consuming it. (Francis Bacon's Head VI; Arts Council Collection; below).

And what does it do to the works themselves? One can't, after all, actively engage with a work of art that's a facsimile'd image enlarged and encountered as a towering billboard. Such an encounter provokes a very different experience, since a painting is more than its image. It's a physical entity with real brush marks. And it's fairly common wisdom that bad to indifferent paintings usually look better in reproduction - the colours often appear more "jewel-like", the messy, seemingly slapdash brushstrokes eliminated (here Howard Hodgkin comes to mind - no. 37 on the list).

And what does it do to the works themselves? One can't, after all, actively engage with a work of art that's a facsimile'd image enlarged and encountered as a towering billboard. Such an encounter provokes a very different experience, since a painting is more than its image. It's a physical entity with real brush marks. And it's fairly common wisdom that bad to indifferent paintings usually look better in reproduction - the colours often appear more "jewel-like", the messy, seemingly slapdash brushstrokes eliminated (here Howard Hodgkin comes to mind - no. 37 on the list).

But in fact, this rule goes for a lot of very good and enduringly interesting paintings too, since a painting isn't a slick piece of graphic design, but a wrought investigation into form, as well as an exploration of ideas, or at least an interestingly packaged proposition. Instantly pleasing is just one of the many things a work of art might be.

If people are tempted to respond to all this with a "So what? Relax. At least it gets people thinking about art, and at least it will encourage a few into a gallery," one wonders how they might respond if it were hundreds of miniature plastic Rodins going on display instead, to "celebrate" the life of the French sculptor. In any case, people have always had terrible reproductions of popular paintings in their homes, without ever thinking of stepping inside a gallery. My parents had Thomas Lawrence's rosebud-lipped Master Charles Lambton in their living room for decades, but neither of them went near a gallery, and they couldn't have named the artist either. (Cornelia Parker's Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, below; Tate)

And no, that wasn't the thing that got me into art. What got me into art was actually going to an exhibition and encountering something that at the time seemed difficult and challenging and raw (a Lucian Freud exhibition at the Hayward in the mid-Eighties, before I even knew who Lucian Freud - nos. 6 and 12 - was), though the initial impetus to seek it out was obviously something that was innate. I came to it fresh, and I doubt if any poster would have had quite that gut-impact. Posters and reproductions do tend to have a somewhat taming, sterilising effect.

And no, that wasn't the thing that got me into art. What got me into art was actually going to an exhibition and encountering something that at the time seemed difficult and challenging and raw (a Lucian Freud exhibition at the Hayward in the mid-Eighties, before I even knew who Lucian Freud - nos. 6 and 12 - was), though the initial impetus to seek it out was obviously something that was innate. I came to it fresh, and I doubt if any poster would have had quite that gut-impact. Posters and reproductions do tend to have a somewhat taming, sterilising effect.

It also makes me feel that the public arts industry - and this venture is supported by the Art Fund - no longer really knows what to do with itself in its efforts to make art accessible. But look, some people are going to find this a wonderful idea, and they're going to really enjoy their encounters with art on billboards. Let me not dissuade them, for I'm really not arguing that Art Everywhere is some kind of beyond-the-pale terrible idea. But nor do I think it's a wonderful, inspiring thing. As a single project, I don't even feel that strongly about it, but I do think, like much else we're relentlessly PR-ed into believing is "inspiring" for its feel-good effects, it's gimmicky, self-promotional and pointless, and I don't think it'll get people into galleries for first-hand encounters.

And, anyway, even if it did, might they not be disappointed that the work is really nothing like (as good as?) the reproductions?

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Comments

Works that 'few people other

I don't really know where to