Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape, Tate Modern

Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape, Tate Modern

The Catalan artist lurched from style to style - and the results weren't always pretty

So how do I feel now, confronted by six decades of Miró in this ambitious Tate Modern survey? It’s the first in the UK for 50 years, as well as the first since the artist’s death in 1983 aged 90. And by bringing together all five of his large-scale triptychs for the first time, the curators have certainly pulled out the stops. So do I feel a little tug in this grown-up, hardened heart? Do I feel drawn once again by the cutesiness of it all, and will I purr with delight at Dog Barking at the Moon (main picture)?

The answer has to be no, and not just because I’m over it, but because, as this exhibition shows, Miró was Miró, the quintessence of the artist we think we know, in relatively few paintings, and for a relatively brief moment in his life. And stylistically, he lurched all over the place, not as an innovator, but rather as an imitator, often years after the movements to which he was drawn had faded politely into art history. And some of the results are really not great. His flirtation with Abstract Expressionism, in his canvas May 1968, 1968-73 (pictured right), is, for instance, a torpid mass of splattered black dripping paint, blotches of primary colour, hand-prints and his usual signature mark-making. There’s no uplifting harmony, but neither is it, as would befit the title, a conflagration of fury and anger. Miró just couldn’t emit that kind of energy, neither in his youth, nor here in his mid-seventies.

The answer has to be no, and not just because I’m over it, but because, as this exhibition shows, Miró was Miró, the quintessence of the artist we think we know, in relatively few paintings, and for a relatively brief moment in his life. And stylistically, he lurched all over the place, not as an innovator, but rather as an imitator, often years after the movements to which he was drawn had faded politely into art history. And some of the results are really not great. His flirtation with Abstract Expressionism, in his canvas May 1968, 1968-73 (pictured right), is, for instance, a torpid mass of splattered black dripping paint, blotches of primary colour, hand-prints and his usual signature mark-making. There’s no uplifting harmony, but neither is it, as would befit the title, a conflagration of fury and anger. Miró just couldn’t emit that kind of energy, neither in his youth, nor here in his mid-seventies.

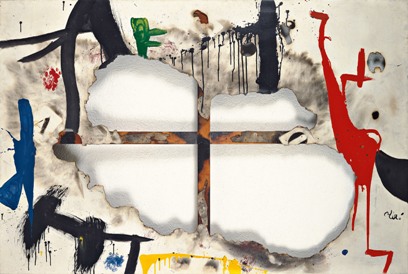

And take his series of burnt canvases, 1973 (pictured left), which are here displayed hanging from frames in the middle of the gallery, like stiffly dried linen. The wooden backing of each canvas is exposed, so that they resemble the bars of a window, and though there is no accompanying pyrotechnical performance, the work seems a rather stiffly elegant nod to Metzger’s auto-destructive artworks of the early Sixties.

And take his series of burnt canvases, 1973 (pictured left), which are here displayed hanging from frames in the middle of the gallery, like stiffly dried linen. The wooden backing of each canvas is exposed, so that they resemble the bars of a window, and though there is no accompanying pyrotechnical performance, the work seems a rather stiffly elegant nod to Metzger’s auto-destructive artworks of the early Sixties.

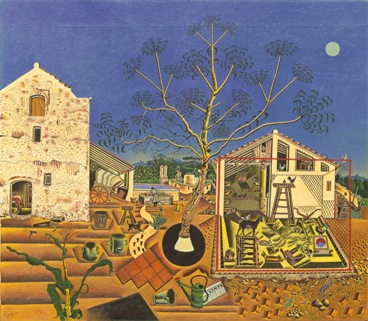

Of course, we should really begin much earlier. Having become acquainted with Surrealism in Paris, Miró, in fact, emerges as fully Miró-esque in the mid-Twenties, though certain of his motifs are already in place in the folksy, meticulously detailed paintings he did of his parent’s farm in Tarragona. These early paintings, such as Vegetable Garden and Donkey, 1918, and The Farm, 1921-2 (pictured right), employ a Cubist space and an intricate, collage-like surface and in them we spot many of the details that will emerge, schematised, just a few years later: the dog barking at a high moon; the tapering ladder; little star-bursts of foliage; plump birds with their decorative fantails; the sinuous curve of brightly coloured footpaths; and foot or hand-prints. This is the enchanted land of children’s book illustration, and with only the barest hint of disquiet in the gnarly twists of a spindly tree.

Of course, we should really begin much earlier. Having become acquainted with Surrealism in Paris, Miró, in fact, emerges as fully Miró-esque in the mid-Twenties, though certain of his motifs are already in place in the folksy, meticulously detailed paintings he did of his parent’s farm in Tarragona. These early paintings, such as Vegetable Garden and Donkey, 1918, and The Farm, 1921-2 (pictured right), employ a Cubist space and an intricate, collage-like surface and in them we spot many of the details that will emerge, schematised, just a few years later: the dog barking at a high moon; the tapering ladder; little star-bursts of foliage; plump birds with their decorative fantails; the sinuous curve of brightly coloured footpaths; and foot or hand-prints. This is the enchanted land of children’s book illustration, and with only the barest hint of disquiet in the gnarly twists of a spindly tree.

From here it’s a short leap to Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), 1923-4 (pictured left), whose tightly arranged signs and symbols and geometries will soon be discarded for something looser, less regimented, as if setting them free from the rigours of reason - though for obvious reasons, finding a visual language for the unconscious has rarely been a wholly successful endeavour for most artists.

From here it’s a short leap to Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), 1923-4 (pictured left), whose tightly arranged signs and symbols and geometries will soon be discarded for something looser, less regimented, as if setting them free from the rigours of reason - though for obvious reasons, finding a visual language for the unconscious has rarely been a wholly successful endeavour for most artists.

And I have not yet talked about politics. This is a survey intent on recasting the Catalan artist as a political artist. He was, indeed, one who had lived in interesting times, spending much of it in self-imposed exile in France during the Spanish Civil War. He then, in what he himself called an “internal exile” returned to Spain to live under Franco’s regime, just as the German Army were marching through the Low Countries and preparing to invade France.

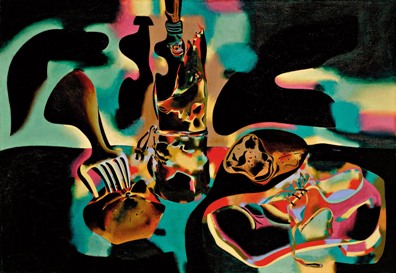

But the curatorial conceit seems woefully laboured, as much as it had been when Tate Liverpool insisted on interpreting individual paintings by Picasso in last year’s Picasso survey Peace and Freedom, through the warped and reductive lens of world affairs. This survey tends towards the less absurdly specific, but even so. The ugly, parti-coloured Still Life with Old Shoe, 1937 (pictured right), is, to my mind, a little less about Miró's psychological response to the political landscape - although I’m certainly not negating its impact on Miró’s life as a whole - and slightly more about the insidious influence of Dalí, as we can surely see for ourselves.

But the curatorial conceit seems woefully laboured, as much as it had been when Tate Liverpool insisted on interpreting individual paintings by Picasso in last year’s Picasso survey Peace and Freedom, through the warped and reductive lens of world affairs. This survey tends towards the less absurdly specific, but even so. The ugly, parti-coloured Still Life with Old Shoe, 1937 (pictured right), is, to my mind, a little less about Miró's psychological response to the political landscape - although I’m certainly not negating its impact on Miró’s life as a whole - and slightly more about the insidious influence of Dalí, as we can surely see for ourselves.

It is therefore a relief to reach the room in which Miró becomes his Miró-esque best. Even for a non-fan like me the selection here from his Constellations series (pictured left: The Escape Ladder, 1940), the first instalment of which he finished in 1940, is beguilingly exquisite. These small paintings on paper are densely packed, with sea-urchin creatures, wormy creatures and microbial life. Unlike Picasso, who could be playful without being twee, the problem with Miró was that he often steered far into cloying terrain. In Constellations, the small working surface perhaps helped contain his worst excesses.

It is therefore a relief to reach the room in which Miró becomes his Miró-esque best. Even for a non-fan like me the selection here from his Constellations series (pictured left: The Escape Ladder, 1940), the first instalment of which he finished in 1940, is beguilingly exquisite. These small paintings on paper are densely packed, with sea-urchin creatures, wormy creatures and microbial life. Unlike Picasso, who could be playful without being twee, the problem with Miró was that he often steered far into cloying terrain. In Constellations, the small working surface perhaps helped contain his worst excesses.

- Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape at Tate Modern until 11 September

Find Joan Miró on Amazon

Find Joan Miró on Amazon

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Comments

...