Andrew Marr: 'I don’t want to look like I'm in pain' | reviews, news & interviews

Andrew Marr: 'I don’t want to look like I'm in pain'

Andrew Marr: 'I don’t want to look like I'm in pain'

Filmmaker Liz Allen explains how she persuaded a wary political journalist to let down his guard

Television audiences love seeing familiar faces in different contexts – whether it’s actors exploring their ancestry in Who Do You Think You Are? or politicians awkwardly busting their moves on Strictly. But there’s always a risk that the camera will reveal more than you’d like.

Liz Allen (pictured below) is an award-winning observational film-maker, who likes to take her time getting under her subject’s skin and building up trust. She never lets the camera out of her hands and makes herself as unobtrusive as possible, so that she’s ready to capture those moments when real life is revealed. Allen's aim is always to let her subjects reveal their genuine selves, rather than putting them in constructed situations for the sake of a pre-ordained narrative. Her previous documentaries include The 15-Stone Baby, a portrait of adults whose fetish is dressing up in nappies, and Short Work, about dwarf actors trying to make it in the entertainment industry, as well as observational series about cancer, department stores and hospitals. When Allen was asked to make a documentary with Andrew Marr by the BBC’s science department, one of her biggest challenges was finding time in his diary between his Sunday politics show on BBC and Start the Week on Radio 4, as well as the books and scripted series he has in the pipeline.

She spent weeks getting to know Marr; their first meeting was in a coffee shop near his north London art studio where he goes to get away from work. He turned up in a paint-spattered T-shirt and Allen was struck by how much the stroke had continued to affect him physically. He needs a brace to support one ankle and has minimal control of his left hand. "The stroke really has disabled him. You don’t see that when he’s on his TV show. For the first month it was just researching the science of stroke and getting to know him and the spaces he inhabits when he’s not on television."

She spent weeks getting to know Marr; their first meeting was in a coffee shop near his north London art studio where he goes to get away from work. He turned up in a paint-spattered T-shirt and Allen was struck by how much the stroke had continued to affect him physically. He needs a brace to support one ankle and has minimal control of his left hand. "The stroke really has disabled him. You don’t see that when he’s on his TV show. For the first month it was just researching the science of stroke and getting to know him and the spaces he inhabits when he’s not on television."

"Although Andrew was more open than I had expected, he made it very clear that there were areas that were no-go zones; he did not want us to delve into his personal life and he was adamant that he didn’t want the viewer to feel sorry for him because of his disability. He would say, 'I don’t want any grimaces on my face, or anything like that.‘"

A few moments into the film we see Marr at home working with a physiotherapist. He’s struggling to manipulate toys meant for toddlers with his affected hand and says: "I really don’t want very much of this on camera." Allen carries on filming and Marr barks, "I said 'No!’" The director explains that it was her first day shooting with him, and at that point he didn’t quite understand her style: "I was just going for a cutaway, but he didn’t realise that and snapped at me. I had to apologise and explain to him that I needed a close-up shot for editing."

For Marr, accustomed to working in a studio with fixed cameras and a script - and to being the interviewer not the subject - it was a big shift. Allen remembers, "Sometimes he’d look at me in a very quizzical way, like I was a blithering idiot, when he didn’t get what I was trying to do." Later in the film the self-described dour Scotsman explains his reluctance to be portrayed as "suffering" in any way: "There's no human crime worse than self-pity; it's the most nauseating human quality of all."

Another challenge was explaining exactly what damage the stroke had done to Marr’s brain in 2013 without breaking the observational style of the film and resorting to clunky diagrams: ‘Luckily we found a wonderful professor, Cathy Price at the Institute of Neurology. We filmed her with Andrew while she explained the medical images they had made of his brain’s anatomy and we only had to enhance the research images a little, so the graphic material become an organic part of the sequence."

The production's time frame included the run-up to Brexit and its aftermath and Allen filmed behind-the-scenes of Marr’s Sunday morning politics show. "Most of the time the politicians in the hospitality room didn’t mind us being there, they were concentrating on getting their points straight so that when they were live on the show, Andrew wouldn’t squish them too much. Hillary Benn did a bit of a double-take when he saw me, a woman wandering around the studio with a camera on my shoulder. Sometimes it felt like I was in an episode of W1A – doors would be shut on me, and people would say sternly 'Now there’s an edit point for you' or talk about not revealing the magic of television, but they did gave us a lot of access."

The production's time frame included the run-up to Brexit and its aftermath and Allen filmed behind-the-scenes of Marr’s Sunday morning politics show. "Most of the time the politicians in the hospitality room didn’t mind us being there, they were concentrating on getting their points straight so that when they were live on the show, Andrew wouldn’t squish them too much. Hillary Benn did a bit of a double-take when he saw me, a woman wandering around the studio with a camera on my shoulder. Sometimes it felt like I was in an episode of W1A – doors would be shut on me, and people would say sternly 'Now there’s an edit point for you' or talk about not revealing the magic of television, but they did gave us a lot of access."

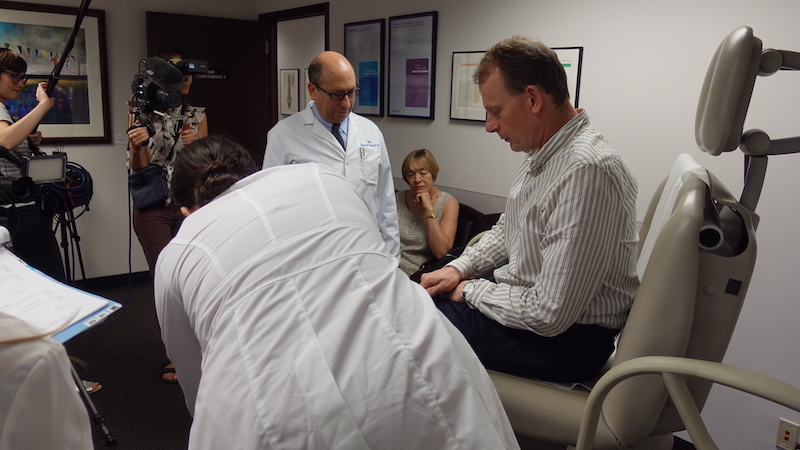

Allen shows the treatments that Marr explored to regain movement and control of his body – intensive physiotherapy and occupational therapy exercises, but also less traditional interventions involving trans-cranial magnetic stimulation and an unorthodox therapy (pictured above) involving injections of an anti-inflammatory drug that’s only available privately in the USA from one doctor. Allen recalls: "Andrew wanted to make sure that he came across on screen as knowledgeable and appropriately sceptical about new treatments which have yet to achieve official acceptance. He didn’t want to look like he was desperate to try anything that would make him better. He worried about his journalistic credibility if he was seen pursuing a quack treatment. He did a lot of research before he embarked on the treatment and before he'd allow us to go with him to Florida to film it. He argues that he's in a rare position as a stroke sufferer because he can afford to try the treatment. He felt that being a guinea pig for those who can't afford it was potentially useful."

Allen hopes the documentary allows people to get to know Marr a bit better; after months of filming together, it's obvious on screen that he became more comfortable with her filming style: "You only see this very serious side to him on his own show, but he does have an amazing sense of humour, and when he’s having a good day, he’s hilarious and very entertaining – I loved his story about Alastair Campbell having a phobia about ketchup. But what I hope most of all is that after you’ve watched it, you understand stroke and the brain better. It’s amazing how once upon a time, if you had a stroke you’d be wheeled into a corner and just left there. Now we know more about what therapy and hard work can do to improve outcome. The brain is more plastic for longer in life than we realised in the past. And we can change the way it works, we’re not stuck with what we’ve got, we can rewire ourselves. I think that’s a very positive message.’

- Andrew Marr: My Brain and Me is on BBC Two on 14 February at 9pm

more TV

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Prisoner, BBC Four review - jailhouse rocked by drugs, violence and racism

Sofie Gråbøl joins a powerful cast in bruising Danish drama

Prisoner, BBC Four review - jailhouse rocked by drugs, violence and racism

Sofie Gråbøl joins a powerful cast in bruising Danish drama

Drive to Survive, Season 6, Netflix review - F1 documentary overtaken by events

Real-life dramas in the paddock were too late to make the cut

Drive to Survive, Season 6, Netflix review - F1 documentary overtaken by events

Real-life dramas in the paddock were too late to make the cut

Add comment