Rumour machines have been thrumming to the tune of “Rattle as next LSO Principal Conductor”. Sir Simon would, it’s true, be as good for generating publicity as the current incumbent, the ever more alarming Valery Gergiev.

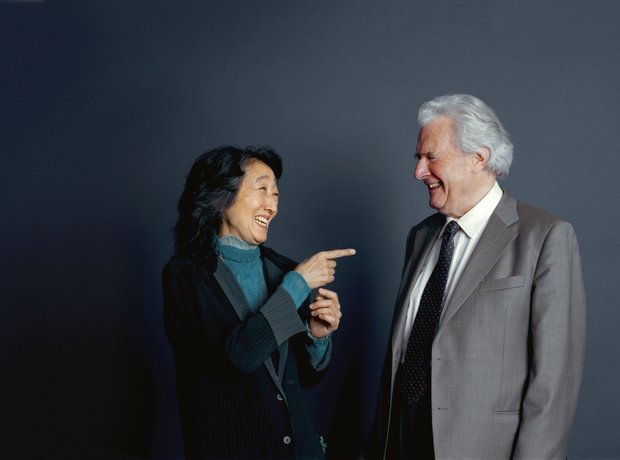

If that more interesting appointment were to be made, we can be sure that the LSO’s beloved Sir Colin Davis, with his unstinting championship for youth, would be looking down approvingly from Up There. This concert was long ago scheduled to be his, and it’s not the first where Ticciati has stepped confidently into the breach. Mitsuko Uchida [3] was there to wave her magic wand right at the start, dedicating Mozart’s Rondo in A minor to Sir Colin (pictured with Uchida below by Gautier Deblonde), who adored it, and hoping as she wrote in the programme to make amends for what had been a bad performance in his studio by playing it “one more time, somewhat better prepared!”

That’s an understatement of the miracle that happened. A single audience-stilling note of E led us tenderly into a clear-sighted but unpredictable journey of gentle melancholy, consolation and even anger: here was the complex humanity of later Mozart in the hands of one who instantly understands the essence. Uchida’s turns and sideslips were perfect, her projection into the large hall as fine as if she were playing for each one of us.

That’s an understatement of the miracle that happened. A single audience-stilling note of E led us tenderly into a clear-sighted but unpredictable journey of gentle melancholy, consolation and even anger: here was the complex humanity of later Mozart in the hands of one who instantly understands the essence. Uchida’s turns and sideslips were perfect, her projection into the large hall as fine as if she were playing for each one of us.

That understanding of human nature, joy and sorrow seamlessly interwoven, continued with the wonderful partnership of Ticciati and the LSO in the G major Piano Concerto K453. It’s always apparent that the galanterie with which Mozart as often begins soon turns inward, but Ticciati had an extra shock in store first by turning it fiercely outward: not for him, or Uchida, the weak image of Mozart as sweet rococo child. The bittersweet second theme, with its keenings making a happy outcome uncertain, was ineffable from both orchestra and then soloist, strings shading their support chords with just as much care as they had the theme itself.

If anything, the slow movement trumped that. Ticciati has always dared to extend silences in music – his Glyndebourne Jenůfa was a searing first lesson in how effective that can be – and they were instrumental in creating suspense as to what the answers to the Andante’s many questions might be. What modulations, what surprises. And then we were encouraged to laugh out loud at the robust wit of the finale’s variations, from the piano’s first delighted entry to the horn charge of the coda, though again there were shadows in the nearly-naked minor variation.

Ticciati delighted in the fire and the wood magic of twilight-zone string rustlingsNaughtily, the LSO hadn’t really advertised an interloper, the world premiere of The Calligrapher’s Manuscript by Matthew Kaner, a participant in the Helen Hamlyn-supported LSO Panufnik Young Composers Scheme. Kaner knows how to put across high and low sonorities, and his woodwind curlicues did convey something of his subject's florid lettering. But the twittering of his first half and the doodles of the second still failed to step up to the mark as foreground interest; as with so many new pieces, it’s the process rather than any strong hooks for the audience which seems to interest the composer. Still, he likes the idea of melody, so let's see what happens next.

There are no problems with thematic hooks in Dvořák [4]’s all too rarely performed Fifth Symphony: they flow in bucolic abundance from the first delighted, gurgling clarinet melody, even if the composer doesn’t always know what to do with them, symphonically speaking. Ticciati delighted in the fire, the free sweep of the first movement’s lyrical respite and the flow of the cellos’ bittersweet Dumka melody in the Andante con moto, the wood magic of twilight-zone string rustlings. And the buoyant Slavonic Dance of the scherzo suggested that this team might tackle the complete sets. It always comes as a bit of a disappointment to me that Dvořák has to lay on an unwarranted sense of struggle in the finale, energetic though it was here, and that he has to end in loud triumph. You just wish he could have laid it all to rest with more forest murmurs, and never more so given the poetry of this very Bohemian performance.

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/david-nice

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] http://www.theartsdesk.com/topics/mitsuko-uchida

[4] http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/classical-cds-weekly-dvo%C5%99%C3%A1k-r%C3%B3zsa-xenakis

[5] http://davidnice.blogspot.co.uk/2009/10/jenufa-mill-wheel-as-fate.html

[6] http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss_1/275-9362751-0041436

[7] https://theartsdesk.com/node/80277/view

[8] https://theartsdesk.com/node/78978/view

[9] https://theartsdesk.com/node/58026/view

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/node/1455/view

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/node/67640/view

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/dvořák

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/mitsuko-uchida

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/mozart

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/lso

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/barbican

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/piano