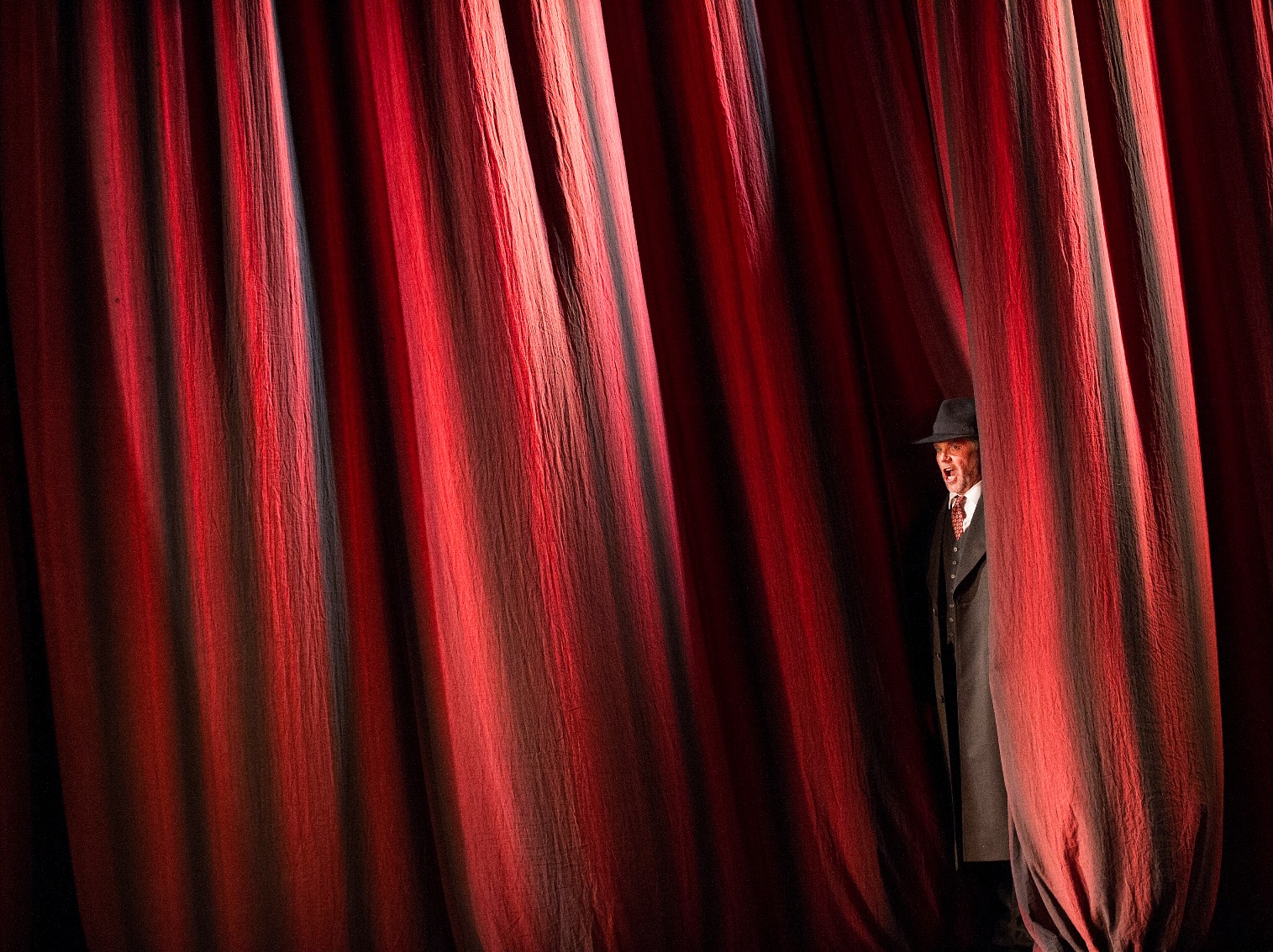

How’s a good time girl to bare her beautiful soul when a director seems bent on cutting her down to puppet size? It doesn't bother me that Peter Konwitschny shears Verdi’s already concise score by about 20 minutes to shoehorn it into a one-act drama; what goes is either inessential or among the usual casualties of standard Traviatas. The spare and economical idea of layered curtains to symbolise the characters' constriction or emancipation is good in principle, too.

There’s not much vocal shapeliness about conductor Michael Hofstetter’s chilly account of the Prelude (apart from a few surprising blaze-ups, the rest is efficient rather than ideally fluent). And we soon realise there’s distancing in Konwitschny’s initial concept: Violetta the seemingly brittle society victim gets pushed together with bookish Alfredo, a duffle-coated nerd catapulted among the DJs and silks. She can change; he can’t, according to Konwitschny. Country love and a dying Violetta leave him as stiff and awkward as ever. There’s no real ardour, no real anger or regrets for poor Ben Johnson [3] (pictured with Winters in the final scene below) to latch on to. Still, this young British tenor is a real asset for ENO – probably more for Mozart and Britten than Verdi or Puccini, for even this lightish role is a bit of a stretch at the top for him.

Konwitschny thinks we’re more likely to believe in Violetta’s sacrifice for Alfredo’s convention-bound father if the daughter she’s supposed to step aside for is shoved on to the stage as a harrowed, pigtailed schoolgirl: the courtesan might do her best for another downtrodden female. This, though, makes father Germont so much the irredeemable bully that the shifting dynamics of the great duet at the heart of the opera go for nothing (and what’s with the gun Violetta pulls towards the end?) Anthony Michaels-Moore [4] (pictured below), after an unsettled start on the first night which found him hectoring the smoother legato lines, is the genuine Verdi-baritone article, and sings his romance of attempted consolation to the devastated Alfredo with real style. But his character remains as one-dimensional as his son’s.

Konwitschny thinks we’re more likely to believe in Violetta’s sacrifice for Alfredo’s convention-bound father if the daughter she’s supposed to step aside for is shoved on to the stage as a harrowed, pigtailed schoolgirl: the courtesan might do her best for another downtrodden female. This, though, makes father Germont so much the irredeemable bully that the shifting dynamics of the great duet at the heart of the opera go for nothing (and what’s with the gun Violetta pulls towards the end?) Anthony Michaels-Moore [4] (pictured below), after an unsettled start on the first night which found him hectoring the smoother legato lines, is the genuine Verdi-baritone article, and sings his romance of attempted consolation to the devastated Alfredo with real style. But his character remains as one-dimensional as his son’s.

For Corinne Winters, there are the same obstacles to creating a real human being. In an uneasy balance between stylisation and naturalism, every move seems phoney: drag the curtains here, jump off the chair and collapse there. Which is a terrible shame because, although hers may not be the most individual of voices, she fills it with intensity and can do everything Verdi asks: the coloratura hectic flushes of the determination to carry on with the high life at the end of the first scene, the lirico spinto ability to pull out the vocal stops for the big, desperate phrase of “Love me, Alfredo” and the curving lines of anguish in the second party scene, the tenderness of the too-late last love duet.

For Corinne Winters, there are the same obstacles to creating a real human being. In an uneasy balance between stylisation and naturalism, every move seems phoney: drag the curtains here, jump off the chair and collapse there. Which is a terrible shame because, although hers may not be the most individual of voices, she fills it with intensity and can do everything Verdi asks: the coloratura hectic flushes of the determination to carry on with the high life at the end of the first scene, the lirico spinto ability to pull out the vocal stops for the big, desperate phrase of “Love me, Alfredo” and the curving lines of anguish in the second party scene, the tenderness of the too-late last love duet.

That final scene ushers in another problem for Winters, though. The red curtains of Johannes Leiacker’s effective designs work well; it’s certainly a bold moment in Konwitschny’s “Scene Three” when, in a fast moving party scene thankfully free of rhe usual gypsies and toreadors, Alfredo’s violence in the big confrontation sees all the red drapes pulled down, the chorus crashing to the ground only to crawl off and leave the heroine to her endgame. That leaves a black curtain at the very back of the stage against which Violetta has to deliver the aria we know as “Addio del passato”.

It’s a measure of Winters’s emotional projection that we can still hear her with her back to the audience and as far away from them as the all too vast Coliseum stage allows. And why can’t Alfredo and Violetta just hold each other for their simple dreams of an illusory future instead of stepping back again to try in vain to pull some invisible curtains back (you get the symbolism very quickly). The intimacy which is so strong a feature of Verdi's semi-domestic opera seems less valid than ever in this vast venue.

It’s a measure of Winters’s emotional projection that we can still hear her with her back to the audience and as far away from them as the all too vast Coliseum stage allows. And why can’t Alfredo and Violetta just hold each other for their simple dreams of an illusory future instead of stepping back again to try in vain to pull some invisible curtains back (you get the symbolism very quickly). The intimacy which is so strong a feature of Verdi's semi-domestic opera seems less valid than ever in this vast venue.

The last image, at least, is strong: the Germonts and hapless Doctor Grenvil singing from the auditorium, Violetta reaching out from the stage before stepping out of the circle of light and into the blackness beyond. But after a too-solid Mimì (Maija Kovalevska) in a Covent Garden Bohème [5] which is as conventional as the Traviata there – time for a change – here was a second consumptive heroine who couldn’t make us shed a tear. And this time we had a soprano who was perfectly capable of doing so in the right circumstances. If you want to see a German regietheater re-think which works, watch the DVD of Willy Decker’s Salzburg production with Anna Netrebko and Rolando Villazón [6]. Although none of the smaller roles made much impact at ENO, the company should be proud of fielding a pair of lovers not too far behind that starry couple; it’s just a shame that Winters and Johnson have a director who works against them.

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/david-nice

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] http://www.theartsdesk.com/opera/don-giovanni-english-national-opera-0

[4] http://www.theartsdesk.com/opera/tosca-english-national-opera-0

[5] http://www.theartsdesk.com/opera/la-boh%C3%A8me-royal-opera-house-0

[6] http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/10-questions-opera-singer-rolando-villaz%C3%B3n

[7] http://www.davidnice.blogspot.co.uk/

[8] http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss_1/278-5840453-0330405

[9] http://www.eno.org/see-whats-on/productions/production-page.php

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/node/1800/view

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/node/1051/view

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/node/57136/view

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/node/27849/view

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/node/1566/view

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/opera

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/eno

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/verdi

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/italy

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/19th-century

[20] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/prostitution

[21] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews

[22] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/london-coliseum