Much more regularly than the seven years it takes the Flying Dutchman's demon ship to reach dry land, the Zurich Opera steamer moors at the Southbank Centre. None of its more recent concert performances up to now has branded itself on the memory as much as its 2003 visit, when chorus and soloists stunned in Wagner's Tannhäuser.

In the first act, the great Wagnerian of today was hailed and well met by a veteran legend still in good shape (don't basses go on for ever?), 67-year-old Matti Salminen as bluff captain Daland. After an unnecessary interval, foisted by the Festival Hall on a company which at home runs its Dutchman for two and a quarter hours without a break, the platform was then lit up by the Senta of Anja Kampe, one of those performers who seem to project the character's inner life with every committed breath.

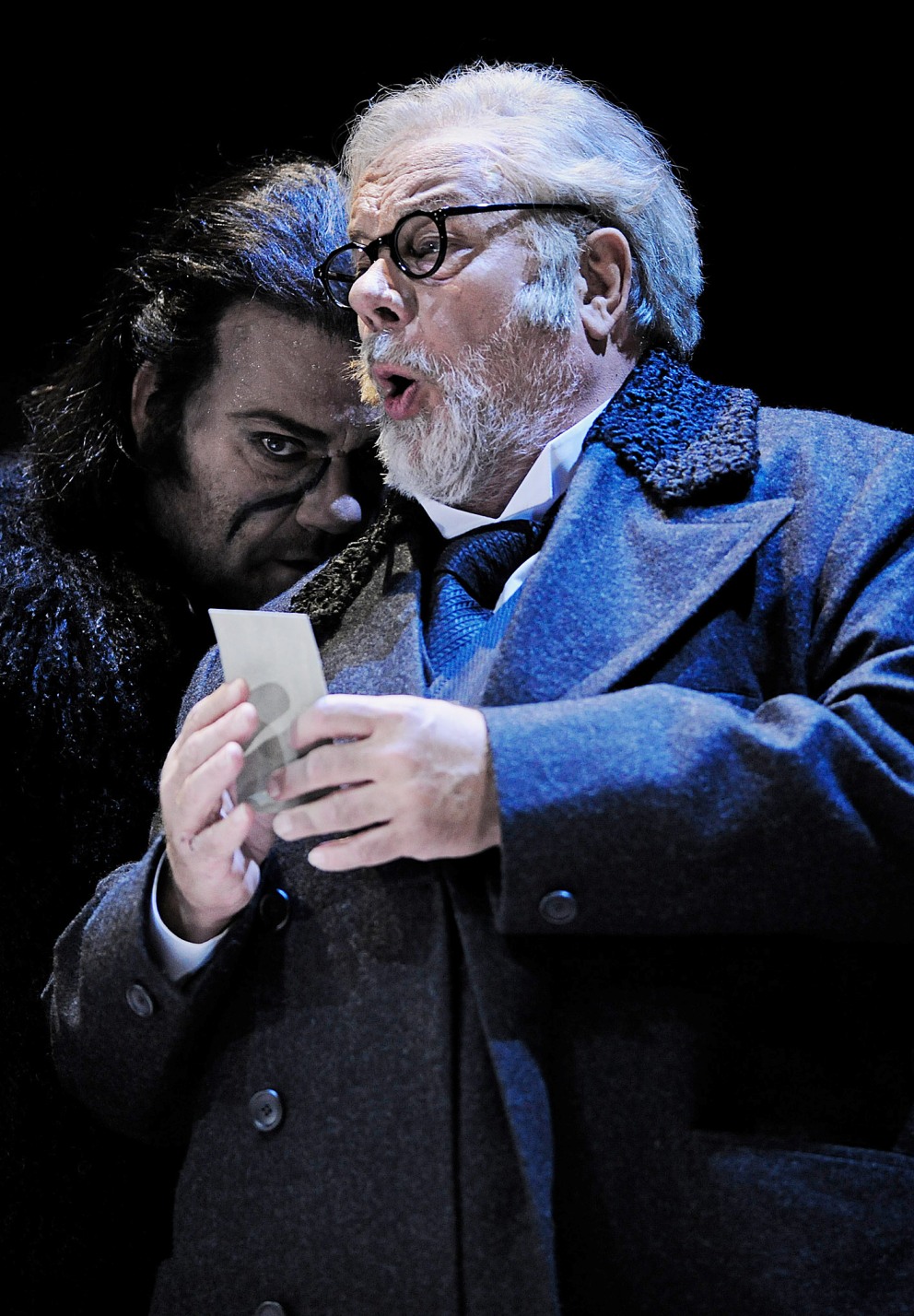

The great overture, Wagner's first signing-in of true genius in 1843, certainly showed off the unusual, cultured tones of the house orchestra, the Philharmonia Zurich, epitomised by the very distinctive timbre of its cor anglais. But conductor Alain Altinoglu seemed more remarkable for elegance than elemental surge, a slight reticence which vanished as soon as the stormy action got under way. The sweetest of light tenors, Schweizer from Ticino Fabio Trümpy, offered the first moment of light relief, ballasted at the other end of the act by Salminen (pictured with Terfel in the Zurich production right), a model of relaxed stage movement and resonant ease who negotiated his Italian opera buffa humour at the start of the duet with surprising agility.

The great overture, Wagner's first signing-in of true genius in 1843, certainly showed off the unusual, cultured tones of the house orchestra, the Philharmonia Zurich, epitomised by the very distinctive timbre of its cor anglais. But conductor Alain Altinoglu seemed more remarkable for elegance than elemental surge, a slight reticence which vanished as soon as the stormy action got under way. The sweetest of light tenors, Schweizer from Ticino Fabio Trümpy, offered the first moment of light relief, ballasted at the other end of the act by Salminen (pictured with Terfel in the Zurich production right), a model of relaxed stage movement and resonant ease who negotiated his Italian opera buffa humour at the start of the duet with surprising agility.

For deep soul, though, we had to wait for the entry of Terfel [4], a magnificent still presence as always, his monologue drawing us in right at the start with its hollow desolation and rising to cosmic despair with hair-raising stops pulled out at "nirgends ein Grab! Niemals der Tod!" ("nowhere a grave! Never death!"). For a snapshot of Terfel's art, the beginning of the second act duet couldn't be bettered: the evenness of the voice throughout the range in pianissimo demonstrated by the emotion of the opening phrase, a sliver of warmth into the silence, rising to a generous beauty of phrasing as the possibility of redemption comes to seem a reality.

For all that, this was not so much a moment to admire flawless technique as to melt at a love duet in which the room truly began to spin. Much of the credit for setting that up had to go to the instantly sympathetic Kampe (pictured left with Terfel in the Zurich production), a wonderful Isolde at Glyndebourne [5] and, as Senta, a visionary able to make her dream real in a rock-solid ballad. Her answering phrases in the duet only heightened the magic set up by Terfel, and though those first top Bs at the climax gave her trouble, the rest were brilliantly tackled and dramatically meaningful. Kampe's intonation throughout was as strong and true as her characterisation.

For all that, this was not so much a moment to admire flawless technique as to melt at a love duet in which the room truly began to spin. Much of the credit for setting that up had to go to the instantly sympathetic Kampe (pictured left with Terfel in the Zurich production), a wonderful Isolde at Glyndebourne [5] and, as Senta, a visionary able to make her dream real in a rock-solid ballad. Her answering phrases in the duet only heightened the magic set up by Terfel, and though those first top Bs at the climax gave her trouble, the rest were brilliantly tackled and dramatically meaningful. Kampe's intonation throughout was as strong and true as her characterisation.

Martin Homrich, a serviceable if rather wide-vibratoed replacement for the advertised Marco Jentzsch as her hapless suitor Erik, provided the necessary foil to her fixation. The final denouement - here using Wagner's hard-hitting original version where Senta's sacrifice results in no post-Tristan floating up to the heavens, presumably an unredeemed ending in the Zurich production - flamed in every department. Kampe electrified her final vows as Terfel generously pushed his voice to a roughness it needed here and the orchestra caught fire.

As always, we marvelled at the Zurich Opera Chorus's burnished agility. Altinoglu accompanied the nimble spin-sters in Act Two with amusing dialogues between bassoons and horns, while the strange meeting of human and supernatural sailors in Act Three was as effective as it can be without the aid of atmospheric production values (though they might have experimented with the Festival Hall spaces more and put the demon crew outside the doors on a higher stalls level instead of onstage). The evening, though, belonged to Terfel, Kampe and Salminen - world-class performances which may be equalled but won't be surpassed in Wagner bicentenary year.

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/david-nice

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] http://www.theartsdesk.com/topics/bryn-terfel

[4] http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/bryn-terfel-royal-festival-hall

[5] http://davidnice.blogspot.co.uk/2009/08/mathildes-zurich-hothouse.html

[6] https://theartsdesk.com/node/17155/view

[7] https://theartsdesk.com/node/34905/view

[8] https://theartsdesk.com/node/79179/view

[9] https://theartsdesk.com/node/514/view

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/node/2751/view

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/opera

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bryn-terfel

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/wagner

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/switzerland

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/southbank-centre

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/19th-century

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/mythology