Death terrifies and fascinates in equal measure: we fear both the journey and the void, but can’t help but poke and prod its weary carcass. That’ll be us soon, as sure as taxes. The promise of eternal life offers to take out death’s sting, and one wonders whether art, rather than offering a straightforward memento mori, really might have a similar function.

The Wellcome Collection’s Death exhibition promises to offer a “self-portrait”. But what can Death possibly look like? More interestingly, what might it feel like? In place of an answer, we have an array of skulls and skeletons, many engaged in an eternal danse macabre, while others indulge in unholy communion with the living.

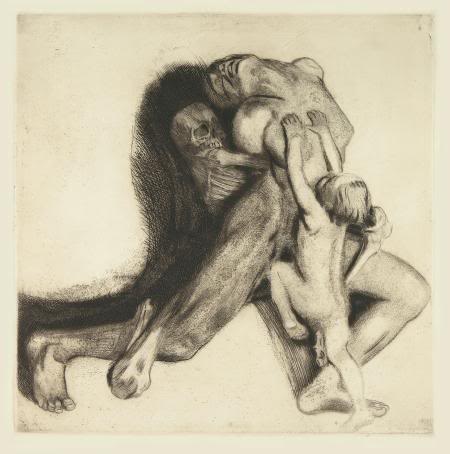

The predator’s skeletal fingers wrap themselves around one generous breast

In Walter Sauer’s 1925 woodblock print, Dance of Death, skeletons leap from their graves in mischievous celebration. In Kawanabe Kyosai’s delicately rendered 19th-century watercolour, Frolicking Skeletons, we find a posse of skeletons passing the time in earthly pleasures, a theme typical of the Japanese Ukiyo-e genre. From the same period, we find German artist Alfred Rethel’s wood engravings: in one, Death, a skeleton in hooded robe, plays a violin consisting of two thighbones, while the dead are slumped at his feet and those still living flee in terror; Cholera sits at the back, dressed like an Egyptian pharaoh.

Like his friend and decadent co-conspirator Baudelaire, Félicien Rops was enraptured by death, sex and skeletons. He’s drawn a skeleton performing cunnilingus on a woman whose face is shrouded by her own wild hair. The predator’s skeletal fingers wrap themselves around one generous breast, a grisly foreshadowing of the woman’s own death, or perhaps simply la petite mort. Rops, a Belgian Symbolist, was apparently exploring the sexual nature of St Theresa’s religious ecstasy.

Apart from a nod here and there to non-western cultures – the Japanese frolickers, masked “death dancers” from the Himalayas, the obligatory photo of a Mexican “Day of the Dead” [3] procession – this exhibition is predominantly European, and specifically Northern European in feel. It begins with a Flemish 17th-century vanitas by Adriaen van Utrecht : a skull garlanded with ivy and surrounded by representations of worldly, transient pleasures. We have Albrecht Dürer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse [4], prints by Otto Dix of soldiers in frozen World War One trenches, one, hollow-eyed, eating his rations beside the worm-eaten remains of his comrades. There is Käthe Kollwitz’s harrowing Death and the Woman, 1910 (pictured right) in which Death pulls a young woman into his skeletal embrace while her child clambers over her. The image is both uneasily sensual and chilling.

Apart from a nod here and there to non-western cultures – the Japanese frolickers, masked “death dancers” from the Himalayas, the obligatory photo of a Mexican “Day of the Dead” [3] procession – this exhibition is predominantly European, and specifically Northern European in feel. It begins with a Flemish 17th-century vanitas by Adriaen van Utrecht : a skull garlanded with ivy and surrounded by representations of worldly, transient pleasures. We have Albrecht Dürer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse [4], prints by Otto Dix of soldiers in frozen World War One trenches, one, hollow-eyed, eating his rations beside the worm-eaten remains of his comrades. There is Käthe Kollwitz’s harrowing Death and the Woman, 1910 (pictured right) in which Death pulls a young woman into his skeletal embrace while her child clambers over her. The image is both uneasily sensual and chilling.

There are also a number of Goyas [5] and Jacques Callots, the first from Disasters of War, the other from The Miseries of War. These fully fleshed victims depicting man’s grotesque inhumanity to man still have the power to move and to shock. And here too one may find oddly sexualised images: a Goya corpse impaled on the branch of a tree as if astride it (pictured left), its sharpened tip erupting between his shoulder blades. Nearby, the soldiers gossip and relax.

There are also a number of Goyas [5] and Jacques Callots, the first from Disasters of War, the other from The Miseries of War. These fully fleshed victims depicting man’s grotesque inhumanity to man still have the power to move and to shock. And here too one may find oddly sexualised images: a Goya corpse impaled on the branch of a tree as if astride it (pictured left), its sharpened tip erupting between his shoulder blades. Nearby, the soldiers gossip and relax.

There are ancient skulls and modern skulls, real, carved, painted, printed and drawn. And as one might expect, there's a side order of black humour. George Grosz’s Face of Death, 1958, shows our old friend to be mercilessly indiscriminate. Skulls have replaced not only the features of the young and the old, the low and the high-born, but have attached themselves to the soles of shoes and are peeking out of bins. Omnipresent and omnipotent Death.

Then there is the gallows humour of the medical student. Six young doctors, in a photograph taken in 1900 (main picture), stand solemnly in a row behind a flayed cadaver on a theatre table; one student nonchalantly holds up the flayed head of the grinning corpse in ghoulish greeting. Written on a blackboard behind the figures is the question, “When Shall We Meet Again?”

The exhibition is necessarily limited in scope, since it all comes from the personal collection of Chicago antique print dealer Richard Harris. So dying, as a deeper, felt experience, which is the kind of exhibition that the Wellcome Collection would usually do so brilliantly, is left unexplored. Instead we have a display which is the result of a life-long obsession, a way, Harris says, of coming to terms with his own mortality. But perhaps the best way to do that is by living.

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/fisunguner

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] http://www.theartsdesk.com/visual-arts/miracles-and-charms-wellcome-collection

[4] http://www.theartsdesk.com/visual-arts/northern-renaissance-d%C3%BCrer-holbein-queens-gallery

[5] http://www.theartsdesk.com/visual-arts/renaissance-goya-prints-and-drawings-spain-british-museum

[6] http://www.wellcomecollection.org/whats-on/exhibitions/death-a-self-portrait.aspx

[7] https://twitter.com/FisunGuner

[8] https://theartsdesk.com/node/55891/view

[9] https://theartsdesk.com/node/33482/view

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/node/51275/view

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/node/79724/view

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/node/16234/view

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/visual-arts

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews