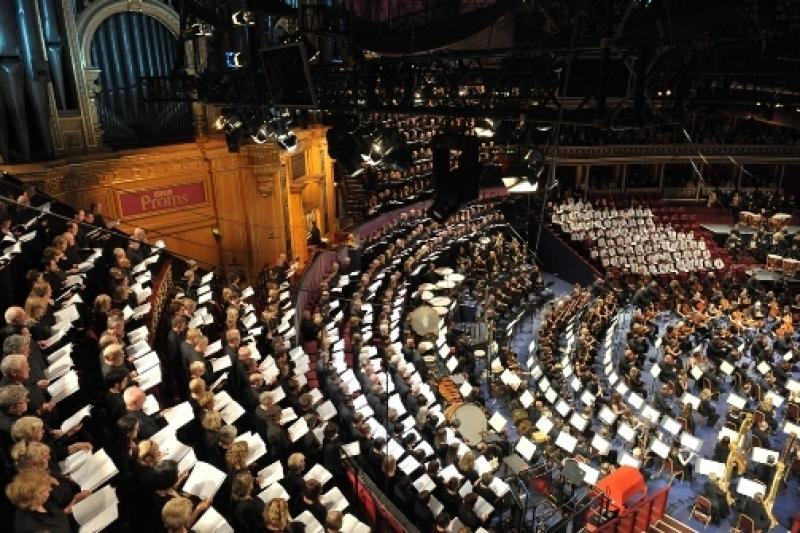

From Middle-earth, middle England and Nibelheim they came, adventurers anxious to acclaim an Unjustly Neglected British Masterpiece. Praise, or curse, their persistence in steering the BBC and the Albert Hall back to Havergal Brian's biggest work after 31 years; hail by all means conductor Martyn Brabbins's flexible command of nine choirs and two orchestras.

Leviathan-like length and size shouldn't get in the way of quality, provided you have brilliant ideas to fill the spaces, as Mahler always did. Brian, at least in the 1920s when he composed this epic, seems to have commanded only hollow gestures and an eclecticism that never goes quite far enough. The Gothic Symphony often feels like the work of a hyperactive child let loose on those famous Hollywood drawers of mood music for films marked "holy", "fearful", "peaceful", "stormy" and pasting the results together any old how. I've nothing against the kind of anti-symphonic thinking which traffics in far-flung contrasts: last year Rued Langgaard's Music of the Spheres [3] did just that. But the quality of Langgaard's invention through all the peaks and troughs held my imagination spellbound; here I fidgeted and sniggered like a naughty schoolboy at the back of my box - and I didn't go into the hall intending to behave like that.

It may well be that once you get to know the music, it feels - as Brabbins described it in interview [4] - like Brian is creatively wrong-footing the listener, heading off in weird and wonderful directions. Given the first-time immediacy of the experience - which is all most of us are going to get - it just seemed for the most part like a terrible, inchoate mess. While the outer movements of each of the two parts at least kept us listening for the occasional moments of celestial refinement between the thrashes, the centrepieces felt nightmarishly turgid - which is part of the point, surely, post-World War One, but again we all need footholds. It didn't help that the vast choral forces kept sagging in pitch - at one point angelically redeemed by distant soprano Susan Gritton - or that, once past an opening which sounded like a crumpled version of Elgar in angry mood, you kept noticing how Brian over-employs xylophones in excelsis and tubas at the bottom of the pile.

The ever-underrated Brabbins (pictured right) kept his usual focus and drive through even the most preposterous flails and twiddles, but it was hard not to wish him better (say with a work like Janáček's Glagolitic Mass, heard on the First Night of the Proms [5], a masterpiece premiered in the same year as the Gothic's completion, 1927; any one of its ideas in this context would have had me sitting bolt upright). Likewise the quartet of soloists, whom you'd have been happy to encounter in Beethoven's Ninth. Italianate tenor Peter Auty [6] and stalwart bass Alastair Miles did what they could to stand guard at either end of the endless sixth-movement ramble; for the second time in two days a mezzo - in this case the admirable Christine Rice [7], who deserves to shine - drew the short straw in terms of what the composer had given her to sing.

The ever-underrated Brabbins (pictured right) kept his usual focus and drive through even the most preposterous flails and twiddles, but it was hard not to wish him better (say with a work like Janáček's Glagolitic Mass, heard on the First Night of the Proms [5], a masterpiece premiered in the same year as the Gothic's completion, 1927; any one of its ideas in this context would have had me sitting bolt upright). Likewise the quartet of soloists, whom you'd have been happy to encounter in Beethoven's Ninth. Italianate tenor Peter Auty [6] and stalwart bass Alastair Miles did what they could to stand guard at either end of the endless sixth-movement ramble; for the second time in two days a mezzo - in this case the admirable Christine Rice [7], who deserves to shine - drew the short straw in terms of what the composer had given her to sing.

Spatial effects made for visual as well as aural spectacle, with children's choirs, timps and extra brass taking up the side rows of stalls where the punters usually sit; but for me there was more magic in the two brief horn calls from the gallery in the previous night's concert performance of Rossini's William Tell [8]than in anything on offer here. The choirs could have done with a stronger backbone of male voices - some senior tenors stood out unflatteringly - but did keep us company with comforting full-throttle triads and unexpectedly electrified in a sudden blaze getting over the final hurdle, where, with a pointedly banal little march leading the way, Brian showed originality in idea as well as scope. But it was a bit late by then. "Whoever strives with all his might/ Him can we redeem" run the lines from Goethe's Faust which Brian engaged as an epigram to the initial conflict. With art over decades, unfortunately, that's not enough. Is it time to put out a recording of this vivid performance to satisfy the enthusiasts, and lay "the Gothic" to rest forever now?

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/david-nice

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/danish-national-symphony-orchestra-dausgaard-royal-albert-hall

[4] http://www.classical-music.com/feature/meet-artists/martyn-brabbins

[5] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/bbc-proms-first-night-proms-grosvenor-bbcso-b%C4%95lohl%C3%A1vek

[6] https://theartsdesk.com/opera/simon-boccanegra-english-national-opera

[7] https://theartsdesk.com/opera/damnation-faust-english-national-opera

[8] https://theartsdesk.com/opera/bbc-proms-william-tell-orchestra-academy-santa-cecilia-pappano

[9] http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b012lkly

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/bbc-proms-2011-theartsdesk-recommends-0

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/bbc-proms-2011-full

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/england

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/royal-albert-hall

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/20th-century

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bbc

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/choral-music

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/proms