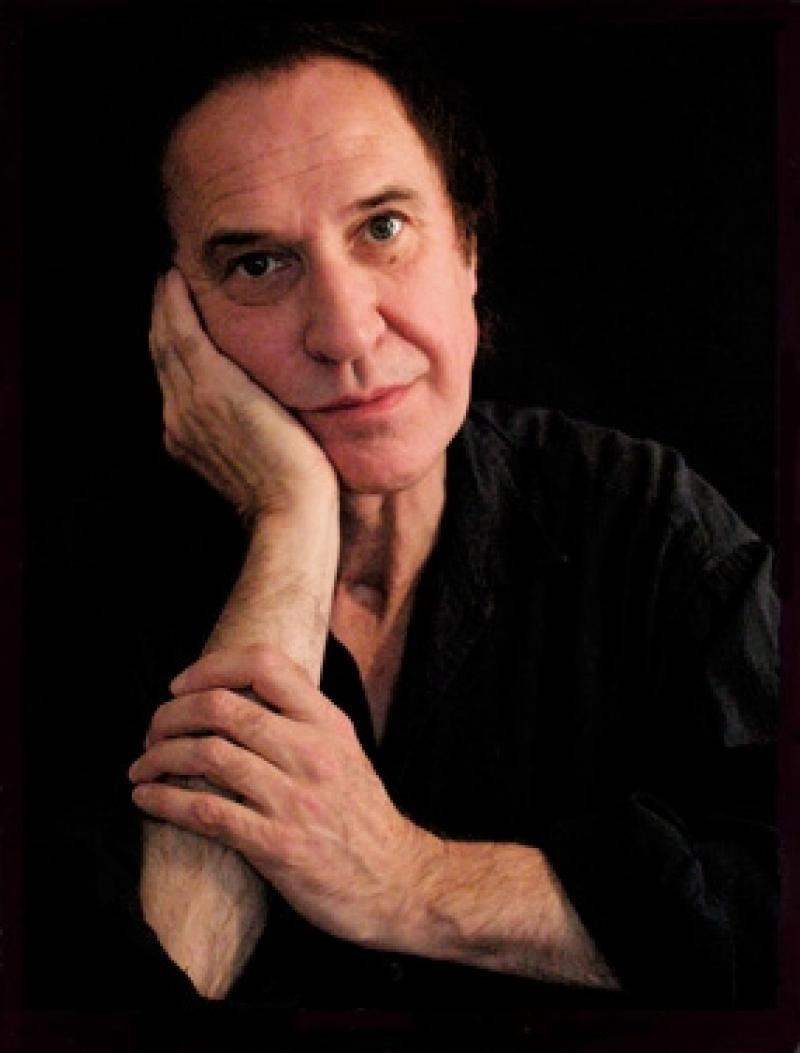

"Compared to the way I feel now", said Ray Davies 50 minutes in, “having a nervous breakdown was a jaunt.” His voice was even, matter of fact. He didn’t look distressed, merely appeared to be stating what he thinks is obvious. Julian Temple’s documentary about The Kinks’s leader and songwriter was packed with such moments – revealing and so open that it was impossible not to be affected by Davies’s low-key passion. This assured portrait was more than the story of a pop star.

The broadcast of Ray Davies, Imaginary Man comes on the back of the release of Davies’s new album See My Friends, a largely disastrous set of re-recordings of songs from his back catalogue made with some ill-fitting and unlikely collaborators. It’s a cliché that The Kinks invented heavy metal with "You Really Got Me”, but a new version with Metallica plumbs the lowest levels of triteness. It's awful too.

As he walked through his London Davies sang and hummed his songs, and it really did seem as though he was a ghost, unseen, unnoticed by passers-by

Still, getting this contemporary recognition has been a long process. The Kinks’s American stadium-rock years were never gong to capture the British imagination. The Jam covered The Kinks during the punk period, but it was the Britpop boom that brought The Kinks hipster credit. The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society sold almost nothing in 1968, but it’s now acknowledged as a musical and observational classic. The path to being stitched into rock’s rich tapestry has always been faltering though – a fine career-spanning box set arrived only in 2008. America’s equally important Byrds got theirs – the first of two – in 1990. Ray Davies, Imaginary Man must be seen as part of this lengthy, intermittent reclamation process.

Ray Davies [3] himself is no stranger to self-examination, which must partly explain why things can take so long in his world. Classic songs like “Waterloo Sunset" draw from his home town and family. As he explained last night, “Come Dancing” was inspired by events at odds with its upbeat feel – the death of his oldest sister on the Lyceum ballroom’s dancefloor on his birthday just after she had bought him his first guitar. His 1994 third-person autobiography X-Ray was an engrossing, yet detached, examination of what made Ray Davies tick.

But Davies hasn't limited himself to music and the printed word. He directed the film Return to Waterloo in 1985 and completed Weird Nightmare, a documentary about Charles Mingus, in 1991. These and the distance with which X-Ray was written suggest that Davies himself is well qualified to make a documentary about himself. But instead, Ray Davies, Imaginary Man was directed by Julian Temple [4], a film-maker with one foot in the culture he grew up with – caught in the documentary Joe Strummer, The Future is Unwritten – and culture from a slightly more distant past – his 1986 film Absolute Beginners.

Temple and Ray Davies have form. Back in 1982 Temple had directed the promo video for “Come Dancing” and its follow up “State of Confusion”. In long form and more recently, Oil City Confidential, his film about Dr Feelgood [5], the R&B outfit that presaged and inspired punk, was equal parts band bio, character study and a psycho-geographic [6] examination of the band’s home turf, Essex’s Canvey Island. His 2010 film Requiem For Detroit? [7]was an elegiac rumination on the depopulated and skeletal remains of the centre of Michigan city. It was no surprise that Ray Davies, Imaginary Man drew on and developed these approaches, the only new ingredient being BBC bigwig Alan Yentob.

Watch Julian Temple's video of The Kinks's "Come Dancing"

The poignant opening set the tone. Davies and Yentob strolled through the decay of Hornsey Town Hall – the setting for the embryonic Kinks's first show. Amongst the bric-a-brac lying around was a sign bearing the logo of Pye, The Kinks's [8] first label. It didn’t look like a prop brought in for the cameras. Davies confessed that 1964, the year of the first Kinks hit, was “the year I was born”.

Yentob was largely unseen and unheard beyond this point. Although chatty, charismatic and warm, Davies’s descriptions of his outlook were at odds with his ease of delivery. At school he realised “it was not a good world I was going into”. He’s happy with his miserablism. “The songs will be here when I’m gone. I don’t ever feel I existed.”

As he walked through his London – Muswell Hill, Highgate, Trafalgar Square, Waterloo Bridge – Davies sang and hummed his songs. And it really did seem as though he was a ghost, unseen, unnoticed by passers-by. Early-morning joggers paid no attention to this singing man in an overcoat and hat. Only the intermittent clips of him recording the See My Friends album with the various collaborators broke the spell.

Bassist Pete Quaife died earlier this year and brother Dave was missing, but The Kinks’s drummer, Mick Avory, did appear. Conscious of the disconnect between The Kinks and the Swinging Sixties, he described the band as characters from Dickens. No matter how primped up they were, they still looked as though they had arrived from 70 or 80 years earlier. It’s the mood that bleeds through “Dead End Street” and its depiction of the reality beyond the Carnaby Street party. Davies said the coffin seen in the promo film “could have been pop culture”.

Watch The Kinks's promo film for "Dead End Street"

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/kieron-tyler

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] https://theartsdesk.com/new-music/ray-davies-hammersmith-apollo

[4] https://theartsdesk.com/film/film-oil-city-confidential

[5] https://theartsdesk.com/film/theartsdesk-qa-guitarist-wilko-johnson

[6] https://theartsdesk.com/film/english-journey-revisited-av-festival-newcastle

[7] https://theartsdesk.com/tv/requiem-detroit-bbc-two

[8] http://www.officialkinksfanclub.co.uk/

[9] http://kierontyler.blogspot.co.uk/

[10] http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b00x21y4/Imagine_Winter_2010_Ray_Davies_Imaginary_Man/

[11] http://www.amazon.co.uk/Ray-Davies/e/B000AP80CK

[12] http://www.amazon.co.uk/Picture-Book-6CD-Kinks/dp/B001GJ5WHU/ref=sr_1_21?s=music&ie=UTF8&qid=1292945307&sr=1-21

[13] http://www.amazon.co.uk/Picture-Book-6CD-Kinks/dp/B001GJ5WHU/ref=sr_1_21

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/node/79369/view

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/node/84087/view

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/node/88216/view

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/node/47495/view

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/node/77291/view

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/new-music

[20] https://theartsdesk.com/tv

[21] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews

[22] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bbc-one

[23] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/pop-music