Two giants of dance died last year: Pina Bausch and Merce Cunningham. Right now audiences aren’t being deprived of seeing why their names are written permanently in lights in dance history (Bausch’s company performs in Edinburgh and London later this year, Cunningham’s is in London in October), but after 2011 they may be. Cunningham’s company will close, while Bausch’s will be in its last of an uncertain three-year grace period.

A world that carries on with rotten Swan Lakes and interminable Lloyd Webber reruns will never again see Biped, Summerspace or Nelken. And the problems that explain why that becomes so could mean that within 25 years we will never again see Mark Morris's [3] L'Allegro [3] or Ashton's Scènes de ballet or Forsythe's Eidos:Telos. Major contemporary works of art gone, their makers half-forgotten. "Perhaps we should go and see dances like we go to see a person we love, and whose time is short. Now, soon or never,” said Byrnes, her soft voice shaking with protest.

Byrnes visits Bausch’s grave and sits there listening silently to the birds. She finds beautiful words: she calls the German a choreographer of “earth”, and Cunningham a choreographer of “air”, his work like “lines that light makes in water”. In a heightened state of mourning, she pursues the afterlife of their dances. It’s a sobering chase.

Unlike ballet, which has various mechanisms as well as a unified academic tradition to preserve it, modern dance is built on individualism, oddities and inventions that have no universal method of noting them for transmission without their creator being there. Merce Cunningham’s packed notebooks are full of aide-mémoires, drawings, charts, numbers, stuff inscrutable to anyone but him. “LIF phrase no 30. AG phrase no 21.” Only LIF, AG and a few others know what those mean.

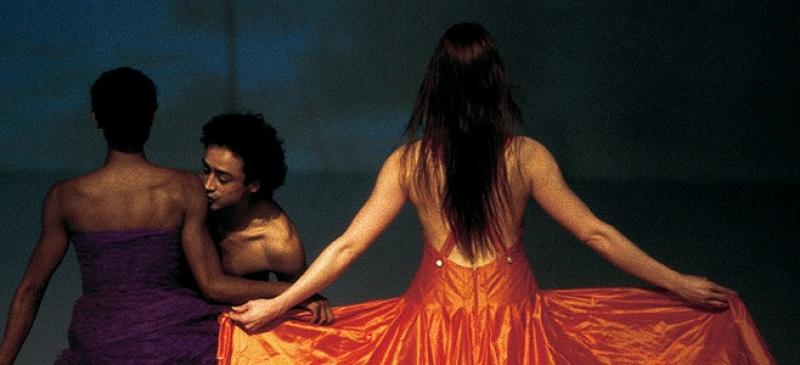

Pina Bausch [4]’s works were just as tricky in their own way, drawing mercilessly on the psychology of her dancers, so that her “revivals” were virtually recreations mined on new dancers. It makes it impossible for future generations to generate the same intensity of need and emotion - in a way, no one else has the right to demand it.

The main obstacle, it emerges, is the choreographers’ own, almost pathological worship of the ephemeral. Cunningham said approvingly, “Dance gives you nothing back. No MS to store away, no paintings to show on walls, no poems to be printed and sold - nothing other than that fleeting moment when you feel alive.” He had made 200 works on his death at 90 last summer, of which only a quarter have any chance at all of being staged in the future since only they have enough materials, notes and videos to pack into “capsules” to offer any company wanting to try. (Even then they'll need one of his dancers to interpret them.)

Bausch left no will, so all her dances are now owned by her 24-year-old son. The matriarch of modern dance Martha Graham left her dances to her controversial companion, a much younger society photographer, who caused the dancers no end of grief in legal suits. America's ballet genius George Balanchine parcelled out his works in bits and pieces to various people, as did Britain's Frederick Ashton. By superhuman effort of cooperation, the Balanchine heirs managed to form a preservation foundation. The Ashton heirs have not. From Byrnes’ research, the Balanchine method was the exception to a general rule, which is that choreographers are irritatingly unhelpful when it comes to posterity.

For Byrnes (and, I'll confess, me too), this is a personal tragedy. Her voice trembles as she considers the possibility of Mark Morris’s dances no longer existing (the US choreographer has made no plans to preserve his dances). She asks Cunningham’s posthumous guardian Robert Swinston how he can allow Cunningham’s pieces to “evaporate”. “Right now I just worry about holding onto the studio,” Swinston says tensely, explaining the limbo the company’s in now. They light candles in their leader’s office every day. They work on his dances to forget he’s gone. But the US never made it easy for Cunningham to survive, and now Swinston has a triple burden - not just to find the money for the studio and the 15 dancers, but to teach Cunningham’s technique, and to coach his repertoire to other companies who may want to do it.

Maybe somebody would fund a small group to organise a revival of a dance, he says hopefully. “You know how those rock bands get together and do revival things?”

Dominique Mercy is his equivalent in Bausch’s company. Even though Bausch’s methods were vastly more psychologically exhaustive for the dancers [5], their sense of loss is not more heartfelt than that at Cunningham’s troupe, just more emotionally expressed. Byrnes quietly keeps bringing them back to essentials: what happens now, who owns the dances, is there a mechanism for the dances to go on, how exactly do dancers carry on dancing dances when the choreographer isn’t there?

Bausch’s dancers insist they have a “duty” to continue (and they have the money too, from their city, for three years at least). Cunningham’s say that’s it; this two-year farewell tour is the end. Trevor Carlson, the MCDC executive director, says that the US system doesn’t allow for companies that don’t create new work: anyway it's unthinkable that Merce Cunningham Dance Company should become “a touring museum” of dance.

The chastening example is that of Martha Graham’s museum company. After her death in 1991 long court cases followed about the artistic ownership of her dances as opposed to their technical ownership. Byrnes remarks perceptively that from her viewing of a recent Graham company performance there is a difference in style between revival and preservation. A show of 1930s works was presented as a lecture-demonstration with voiceover, as if the Graham dancers had no confidence in the audience. “I guess we’re trying to survive without money and with an audience that has no idea what we’re putting out there. It’s really sad. People say, I had no idea - who is Martha Graham?” explains Jacqueline Bulnes, one of the Graham performers.

As Bulnes implies in the tone of her voice, it’s outrageous that even titans in dance are forgotten so speedily. But it is certainly the result (I’d say) of this current dilatory attitude among the dance community to finding tools to preserve work of obvious value to a generation’s contemporary art.

For Balanchine’s work in the US it was complex, drawing together many people, but it was done. Today companies around the world perform his works, as they are recorded, licensed by his guardians. As Barbara Horgan, the Foundation’s instigator and chairman, says, even if you see a bad performance of Serenade here and there, Serenade itself survives.

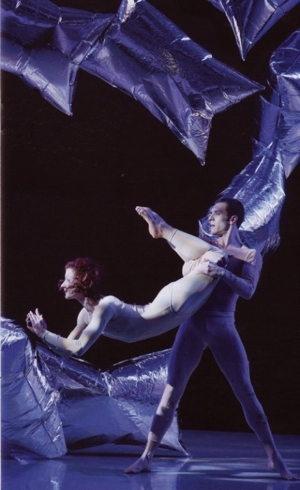

Byrnes observes that the difference in modern dance seems to be that the works, even in revivals, were continually being reinvented by their choreographers. When Rambert performed Rainforest this spring [6] (picture right, Chris Nash for Rambert), a 1968 work never until then performed by an outside company, its stagers were drawing on versions Cunningham himself had changed over the 40 years - which one would be “right” to preserve? And what are the audience’s rights in the matter? Or those of the society to have records of its art? And anyway are those who passionately claim that dance’s details can never be reproduced only really indulging their own memories? Her questions come thick and fast, and acutely aimed to draw blood.

Byrnes observes that the difference in modern dance seems to be that the works, even in revivals, were continually being reinvented by their choreographers. When Rambert performed Rainforest this spring [6] (picture right, Chris Nash for Rambert), a 1968 work never until then performed by an outside company, its stagers were drawing on versions Cunningham himself had changed over the 40 years - which one would be “right” to preserve? And what are the audience’s rights in the matter? Or those of the society to have records of its art? And anyway are those who passionately claim that dance’s details can never be reproduced only really indulging their own memories? Her questions come thick and fast, and acutely aimed to draw blood.

She leaves one big question unasked: the political one, in a world of vanishing faith in subsidised arts. If all that dance is willing to be is a sandcastle built at low tide, which the high tide will swiftly sweep away, then it certainly puts itself at a disadvantage next to all the other artforms scrapping for survival in the jungle. Who in the results-obsessed, bean-counting world of today is willing to support an artform that uniquely abstains from saving itself?

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/ismene-brown

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] https://theartsdesk.com/dance/mark-morriss-lallegro-il-penseroso-ed-il-moderato-london-coliseum

[4] https://theartsdesk.com/dance/theartsdesk-qa-meeting-pina-bausch

[5] https://theartsdesk.com/dance/kontakthof-tanztheater-wuppertal-pina-bausch-barbican-theatre

[6] https://theartsdesk.com/dance/art-touch-rainforest-linha-curva-rambert-sadlers-wells

[7] http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00t6vcm

[8] http://www.eif.co.uk/agua

[9] http://www.sadlerswells.com/show/Tanztheater-Wuppertal-Pina-Bausch

[10] https://theartsdesk.com/node/11023

[11] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/barbican

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/node/1260/view

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/node/43/view

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/node/13721/view

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/node/16288/view

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/node/13713/view

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/dance

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bbc

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/history

[20] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/reviews