Tubular Bells, the first half of which is being currently revived as a live piece in the UK, sold between 15 and 17 million units worldwide. Quite apart from the work’s innocence being co-opted and made spooky in William Friedkin's The Exorcist, there was something about Mike Oldfield’s first stab at quasi-symphonic rock which seduced the music-consuming public.

Borrowing the repeated motifs of Minimalism – most specifically Terry Riley’s Rainbow in Curved Air – and similarly cyclical tropes that made Ravel’s Bolero and Grieg’s Peer Gynt so audience-grabbing, Tubular Bells wallowed in cliché but also broke new ground: this was one of the first examples of a musician recording most of the tracks himself – guitars, keyboards and percussion – but the mostly instrumental piece’s scale, spread over two sides of an LP, was also innovative, in pop or rock at least.

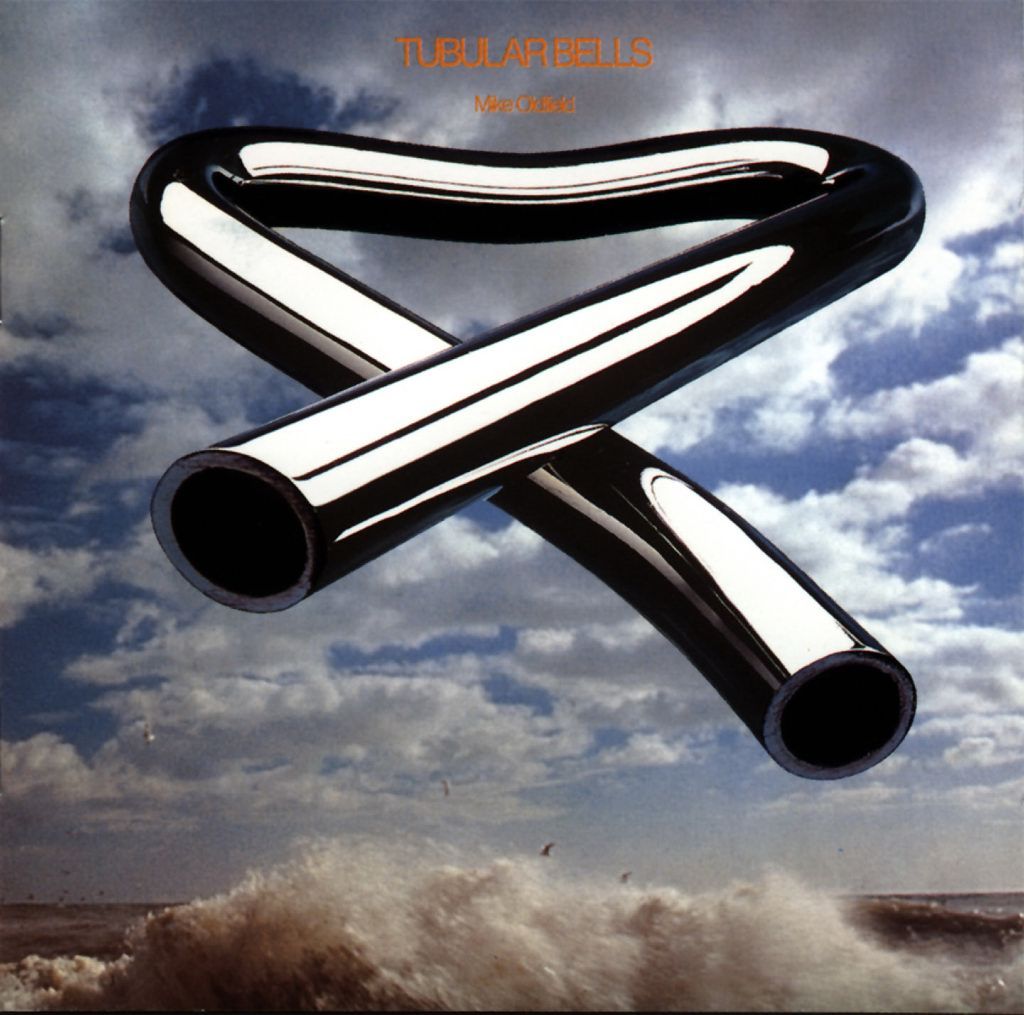

I am not sure whether to feel pride or shame but I played a part in the piece’s success. I had met Richard Branson – who signed Oldfield to his new Virgin label after hearing his demos – in 1967, when we were both involved in student journalism. He contacted me again in 1973 as he was about to launch his first release – Tubular Bells (pictured right). I was by then working on Second House, a fairly wild Saturday-night arts programme on BBC Two. The show was distinguished by a shambolic and knife-edge sense of experiment: performance artist Stuart Brisley lying in a bath of offal would be followed by a performance of David Bedford’s piece “With 100 Kazoos”, a cacophonous audience participation effort and the Mike Westbrook Band paired with Henry Woolf doing brilliant political satire.

I am not sure whether to feel pride or shame but I played a part in the piece’s success. I had met Richard Branson – who signed Oldfield to his new Virgin label after hearing his demos – in 1967, when we were both involved in student journalism. He contacted me again in 1973 as he was about to launch his first release – Tubular Bells (pictured right). I was by then working on Second House, a fairly wild Saturday-night arts programme on BBC Two. The show was distinguished by a shambolic and knife-edge sense of experiment: performance artist Stuart Brisley lying in a bath of offal would be followed by a performance of David Bedford’s piece “With 100 Kazoos”, a cacophonous audience participation effort and the Mike Westbrook Band paired with Henry Woolf doing brilliant political satire.

I heard the Mike Oldfield piece and imagined a live version in the studio. Second House’s execs agreed, and Mike Oldfield brought along Mick Taylor of The Stones [3], Steve Hillage, Fred Frith, Mike Ratledge, David Bedford, Pierre Moerlein and other musicians associated with the label and the early 1970s avant-garde. Director Tony Staveacre, noted for his imaginative multi-camera studio work, visualised the piece beautifully, responding sensitively to the beguiling fluidity of the repeated motifs and the piece’s hallmark moments of drama.

The live version was presented soon afterwards at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall, to which Charles Hazlewood and his All Stars will return with the iconic piece on 6 December. Hazlewood regularly works with Will Gregory of Goldfrapp and Adrian Utley of Portishead, the duo who wrote a stunning new soundtrack for Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc [4]. A few months ago, they put together two concerts celebrating the music of Terry Riley. It was Adrian Utley, looking for another similar collaborative project, who came across the BBC Two version of Tubular Bells and suggested it to Hazlewood. “When I had finished rolling around the floor laughing,” the conductor says, “I thought, why not? It does rumble on as one of the distinct parts of the UK’s musical DNA.”

Hazlewood is too young to have witnessed Tubular Bells when it first came out: “I thought of it as something that geeks listened to, the people who were nuts about Rush [5]and early Genesis [6], all the things I sneered at, or guys who would chin on about which turntable they were using or what woofers were in their speakers.” Although people like to think of it as a Minimalist piece, he adds, “It isn’t really, it just wears some of the clothes of Minimalism. It’s incredibly cheesy, with some fairly execrable sections in it, bits which, to be fair to Oldfield, he’d created when he was a schoolboy. But once I’d seen the live version, which was quite different from Oldfield’s multi-tracking, I was convinced.”

Mike Oldfield performs Tubular Bells

The piece needs to be seen in context, as a product of early-1970s British soft psychedelic whimsy, with a childlike and loony innocence also found in early Pink Floyd, The Incredible String Band and Kevin Ayers’s The Whole World – a band which included Mike Oldfield in its early days, as well as David Bedford. Oldfield was rooted in folk: he had started out in an acoustic duo with his sister Sally and there are plenty of appealing but inevitably generic references to a nostalgic English pastoral style, which colours some 20th-century classics as well as the less protest-driven end of the folk revival. Tubular Bells spoke to the people who, in the early 1970s, longed for the innocence of childhood and dreamed of "going back to the country", a recurring theme in our island’s cultural history, and one which undoubtedly has universal appeal.

Hazlewood is a populariser who embraces the audience in a way that turned the evening into something much more lively than an ordinary concert

For last Friday's Bristol performance, which will be repeated next month in London and Gateshead, Charles Hazlewood put together a brilliantly conceived programme, both didactic and entertaining. Tubular Bells was top of the bill, preceded by three pieces that put it into the context of Minimalism. Hazlewood is both teacher and preacher – he would make the perfect salesman – and he manages to make complex musical matters sound simple, dosing his articulate exposition with humour and a great deal of boyish charm. He is a populariser who really knows his stuff and he embraced the audience in a way that turned the evening into something much more lively than an ordinary concert.

“Rainbow in Curved Air”, the evening’s opening piece, was played by an ensemble that included Adrian Utley (pictured below left), Will Gregory, Graham Fitkin, Ruth Wall and others. Hazlewood describes it as “the aural equivalent of climbing inside a giant lava lamp”, and as the organ loops swirled away, coming and going, Riley’s salvo against the conventions of goal-orientated narrative music took its hypnotic hold. The Steve Reich [7]that followed, “Four Organs”, went one step further in the musical mantra stakes, repeating and stretching a chord many times over 15 minutes.

The Farfisa organs were kept in order by a strict and continuous beat played out on the maracas – heroically, considering the length of the piece – by percussionist Joby Burgess. He never once faltered and demonstrated exceptional physical stamina while manifesting the near-ecstasy that this trance-like pulse was creating. At a Carnegie Hall performance in the late 1960s, the audience couldn’t bear it and fights broke out. A woman walked up to the front of the hall and banged her head on the edge of the stage screaming for the piece to stop. In Bristol the Minimalist-friendly crowd, in characteristically laid-back West Country mode, lapped it up, listening with rapt attention and clearly enjoying the piece’s daring focus on the here and now.

The Farfisa organs were kept in order by a strict and continuous beat played out on the maracas – heroically, considering the length of the piece – by percussionist Joby Burgess. He never once faltered and demonstrated exceptional physical stamina while manifesting the near-ecstasy that this trance-like pulse was creating. At a Carnegie Hall performance in the late 1960s, the audience couldn’t bear it and fights broke out. A woman walked up to the front of the hall and banged her head on the edge of the stage screaming for the piece to stop. In Bristol the Minimalist-friendly crowd, in characteristically laid-back West Country mode, lapped it up, listening with rapt attention and clearly enjoying the piece’s daring focus on the here and now.

Ruth Wall followed with another Reich piece, “Piano Phase”, originally for two keyboards but reworked for her own instrument, the harp. In a piece that weaves together two voices that start out with the same simple phrase in unison and are gradually pulled apart by a progressive offset, in a Minimalist take on the canon, she literally played with her recorded alter ego. The magical effect was somewhat spoilt by gremlins in the PA, and the filigree sound of intertwined harp sounds, as if a cascade of water were being deconstructed, was unfortunately marred by distortion.

The fun (and anxiety) the musicians were clearly experiencing was contagious

Originally presented at 1am in the rain at Glastonbury earlier this year, the Charles Hazlewood All Stars’ version of Tubular Bells – transcribed with some difficulty from the BBC Two recording – closed the evening. In his introduction, Hazlewood apologised for the piece’s shortcomings while acknowledging the nation’s debt to this iconic piece of 1970s prog rock. Some of the performance was halting - there were some obvious mistakes - but the piece was enhanced by the cliffhanging uncertainty of a live performance: the constituent elements of Oldfield’s piece are ridiculously simple while the structure is more intricate and unpredictable. The fun (and anxiety) the musicians were clearly experiencing was contagious, and the audience went happily along with playing that may not have been note-perfect but displayed a heartfelt engagement with the material which avoided the irony that would have robbed this less-than-perfect piece of the undeniable charm that has made it a classic.

The finale, that originally starred Viv Stanshall announcing with appropriate mock-pomp the instruments in the band, featured, rather appropriately, Tony Staveacre, the original director of the TV version that had inspired Adrian Utley and convinced Hazlewood in the first place. As the piece climbed, with echoes of Grieg’s Peer Gynt, to a finale that hovered between irony and cheese, he gave the part just the right upper-class stentorian tone. As the evening closed, not only had the audience revisited the soundtrack of a bygone era – and one of its signature horror flicks - but heard just how it fitted into the much more rigorous universe of Minimalism. Hats off to Hazlewood and his friends for producing an evening’s superb entertainment that was both thought-provoking and fun.

Links

[1] https://theartsdesk.com/users/markkidel

[2] https://www.addtoany.com/share_save

[3] http://www.theartsdesk.com/film/dvd-release-ladies-gentlemen-rolling-stones

[4] http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/jeanne-darc-au-b%C3%BBcher-london-symphony-orchestra-alsop-barbican

[5] http://www.theartsdesk.com/new-music/rush-o2-arena

[6] http://www.theartsdesk.com/new-music/peter-gabriel-hammersmith-apollo

[7] http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/reverberations-influence-steve-reich-barbican

[8] http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss

[9] http://itunes.apple.com/gb/album/tubular-bells-deluxe-version/id319494158

[10] http://ticketing.southbankcentre.co.uk/find/music/gigs-contemporary/tickets/the-charles-hazlewood-all-stars-play-tubular-bells-61484

[11] http://tickets.thesagegateshead.org/tickets/reserve.aspx

[12] https://theartsdesk.com/node/2875/view

[13] https://theartsdesk.com/node/4179/view

[14] https://theartsdesk.com/node/2529/view

[15] https://theartsdesk.com/node/4305/view

[16] https://theartsdesk.com/node/78916/view

[17] https://theartsdesk.com/new-music

[18] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/features

[19] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bristol

[20] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/1970s

[21] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/bbc-two

[22] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/guitar

[23] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/minimalism

[24] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/percussion

[25] https://theartsdesk.com/topics/progressive-rock