Tippett Retrospective, Osborne, Heath Quartet, Wigmore Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Tippett Retrospective, Osborne, Heath Quartet, Wigmore Hall

Tippett Retrospective, Osborne, Heath Quartet, Wigmore Hall

Revelatory Tippett from a phenomenal pianist and the most poised of young string quartets

For those of us who’d held fast to the generalisation that Michael Tippett went awry after 1962, it seemed emblematic that pianist Steven Osborne and the Heath Quartet were never to meet in a concert of two halves. After all, didn’t Tippett’s music split and splinter into a thousand, often iridescent atoms after his second opera, King Priam? Its satellite piece, the Second Piano Sonata, seems to sit restlessly, and quite deliberately, on the fault line.

The sequence of hard-hitting piano followed by ethereal strings was bracketed by two heaven-storming chords: the one that explodes at the start of the Second Sonata, finally either squeezing the life out of all contradictions in its supernatural vice or proposing a new beginning, and another which suggests unfinished business for the wide-awake 86-year-old composer at the end of the Fifth String Quartet.

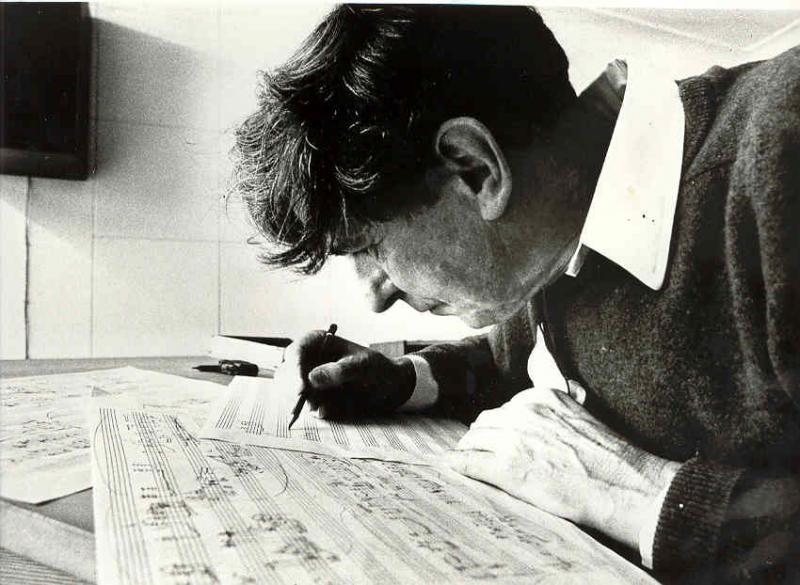

Osborne (pictured right by Eric Richmond), also wide awake in every bar of the Second Sonata, crisply hurled down various mosaic tiles of what music might be in the 1960s, among them war stridings from Priam, a rippling lyricism which the opera never quite achieves even in its most would-be transcendent moments, and bitonal capers half strip-cartoon, half Messiaen. Then in the Third Sonata he settled to the opposite poles of outer-movement dance energy – lopsided and unpredictable but benign, however dissonant – and a calm elaboration of chords which start as stars and become supernovas in an improvisatory-feeling central meditation.

Osborne (pictured right by Eric Richmond), also wide awake in every bar of the Second Sonata, crisply hurled down various mosaic tiles of what music might be in the 1960s, among them war stridings from Priam, a rippling lyricism which the opera never quite achieves even in its most would-be transcendent moments, and bitonal capers half strip-cartoon, half Messiaen. Then in the Third Sonata he settled to the opposite poles of outer-movement dance energy – lopsided and unpredictable but benign, however dissonant – and a calm elaboration of chords which start as stars and become supernovas in an improvisatory-feeling central meditation.

Extreme genius in a composer who, unlike his near-contemporary Britten nevertheless feels whole and sane – for better and for worse, besides which you can't compara incomparables – stood revealed in two phenomenal finales. Osborne likeably explained the palindrome of the Third Sonata’s Allegro Energico, which runs backward once it’s reached its most emphatic poundings and then starts all over again going forward (he told us how his tutor, the Tippett expert Ian Kemp, saw it as a beast rattling its cage). Simply to play it requires formidable technique, but to keep the essential patterns clear in all the welter of notes was Osborne’s unique achievement: and, wonderful as it was to discover the sonatas in his superb Hyperion recording, there’s no substitute for the exhilaration of hearing this piece live.

Follow that? Only the poised and poetic Heaths (pictured left by Sussie Ahlburg) could do so, showing the fluid maturity of a great quartet in stitching together the song-fragments of the Fifth Quartet’s first movement. But it was the great finale which crowned, or haloed, the evening. As Oliver Soden reminded us in his impassioned notes, Tippett’s risky model was the “Song of Thanksgiving” at the heart of Beethoven’s Op. 132 Quartet which this same team had played so exquisitely in part, descending in cages while the reunited prisoner and his wife sat exhausted against a wall, in the tear-jerking coup of Calixto Bieito’s very mixed-bag ENO Fidelio. Tippett rises to its challenge with unpredictable lines cleared of all human suffering, despite the glissando sighs: an Apollonian endgame so very far removed from the hauntings of Britten’s parallel masterpiece, his Third Quartet.

Follow that? Only the poised and poetic Heaths (pictured left by Sussie Ahlburg) could do so, showing the fluid maturity of a great quartet in stitching together the song-fragments of the Fifth Quartet’s first movement. But it was the great finale which crowned, or haloed, the evening. As Oliver Soden reminded us in his impassioned notes, Tippett’s risky model was the “Song of Thanksgiving” at the heart of Beethoven’s Op. 132 Quartet which this same team had played so exquisitely in part, descending in cages while the reunited prisoner and his wife sat exhausted against a wall, in the tear-jerking coup of Calixto Bieito’s very mixed-bag ENO Fidelio. Tippett rises to its challenge with unpredictable lines cleared of all human suffering, despite the glissando sighs: an Apollonian endgame so very far removed from the hauntings of Britten’s parallel masterpiece, his Third Quartet.

As for the overall impact, I wanted to buy all three scores on the spot, while my companion, who came to the concert fresh from her seventh year running a mud hotel in Mali and reckons I’m a snob for not fully embracing The Doors, thought Osborne’s Tippett was “pure rock and roll" – she has a point, and there's also great jazz there - as well as finding, like everyone else in a too-sparse audience, the quartet absolutely spellbinding. Who knows, maybe Graham Vick’s sensational Birmingham Opera Company will make me love one of the later operas, too, when it tackles The Ice Break next spring.

rating

Share this article

more Classical music

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Add comment