Yuletide Scenes 5: Hunters in the Snow | reviews, news & interviews

Yuletide Scenes 5: Hunters in the Snow

Yuletide Scenes 5: Hunters in the Snow

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's wintry panorama is the last in our series of beguiling seasonal scenes

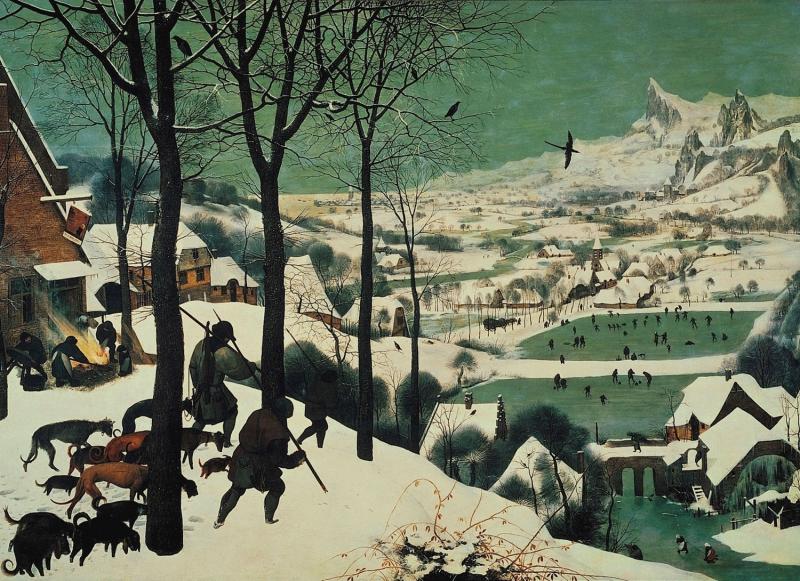

The great Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder was instrumental in developing landscape painting as a genre in its own right. Hunters in the Snow, 1565, is one of five surviving paintings (Bruegel painted six) in his cycle depicting The Labours of the Months. Populated by villagers, peasant workers, farmers, hunters and children, each painting is of a panoramic landscape at a different time of year.

This chilly winter scene is a Christmas card favourite. But Bruegel is an artist whose work has also inspired art house directors, contemporary writers and modernist poets. Hunters in the Snow features in two Tarkovsky films, Solaris and The Mirror. More recently, it featured in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia. That an image so closely associated with festive jollity should also be used in a way that underlines a sense of haunting unease isn't actually that surprising: Bruegel’s painting is powerful exactly because it provokes a sense of uneasy ambivalence.

A small group tend an open fire, which is beginning to look decidedly out of control. Everything feels a little provisional and precarious

It’s certainly an idealised scene, this snow-muffled land that dips steeply into a flat-bottomed valley where children in silhouette can be seen skating and playing ice hockey on a frozen lake. The spectacular peaks in the distance also make you wonder just how many mountainous ranges can be found in the Low Countries. Painted at a time of religious upheaval in the Netherlands, Bruegel was probably depicting country life how he imagined it once was, or how it should or could be.

Bruegel popularised the snowy landscape, influencing artists such as the deaf-mute painter Hendrick Avercamp, who specialised in jolly, silvery-hued scenes of ice-skaters, young, old, rich and poor. It was the epoch of the Little Ice Age, which chilled the Northern Hemisphere from the 16th to the 19th centuries (the Thames was last frozen solid in 1814, the year of the river’s last frost fair). In Hunters in the Snow one can almost feel the biting cold penetrate one’s bones, and even though most of the picture is taken up by landscape Bruegel has managed to give an extraordinary sense of light and space.

So what story does this painting tell? To our left, with their stooped backs presenting a strong outline against the snow and the light, we encounter the three hunters, trudging wearily through a carpet of white. Following close behind are their hunting dogs, each looking really rather sorry for itself. Two of the huntsmen are returning empty-handed, whilst a third, the most prominent, has only a dead fox hanging limply from his spear. It has been a disappointing day.

Further left, there is an inn, its wonky sign threatening to fall with just one gust of wind. Outside, a small group tend an open fire, which is beginning to look decidedly out of control. Everything feels a little provisional and precarious. A black bird is swooping low, while four are perched on branches. Do they convey a sense of foreboding? Cutting across the foreground in a sharp diagonal, and descending the snowy precipice, are the frost-dappled trees, their thin, black trunks rising high into the heavens, their branches creating a delicate pattern against the mint-grey sky. Beyond, the whole town is laid out dizzyingly before us, and indeed, there is something almost vertigo-inducing in this scene. It is both exhilarating and slightly unsettling.

This is a painting that offers us the light and shade of human existence. Bruegel’s hardy peasants toil through long, bitter winters, often gaining little or no reward. We see, however, that there is also delight to be had from being part of the cycle of nature. The tired hunters look down at a joyful, playful scene, but play no part in it themselves. Joy is ephemeral – or perhaps like the children on the ice, it belongs just over there, out of reach. We can chase it, but there are no guarantees. We might even catch snatches of it, but, like snow, it is likely to evaporate.

Share this article

more Visual arts

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Add comment