A Monstrous Reflection: on staging Caligula | reviews, news & interviews

A Monstrous Reflection: on staging Caligula

A Monstrous Reflection: on staging Caligula

The director of English National Opera's new production gets inside an infamous head

"How light power would be and easy to dismantle no doubt, if all it did was to observe, spy, detect, prohibit, and punish; but it incites, provokes, produces. It is not simply eye and ear: it makes people act and speak." Michel Foucault, Power

Caligula is a portrait of a tremendous soul in terrible crisis. In Albert Camus’s Caligula, Detlev Glanert has found a gargantuan character – a man whose dreams become his society’s nightmares. After the death of Drusilla, his sister and lover, Caligula’s world loses meaning. Life becomes absolutely unsatisfactory. In Camus’s words, "he becomes obsessed with the impossible and poisoned with scorn and horror, he tries through murder and the systematic perversion of all values, to practice a liberty which he will eventually discover is not the right one." Caligula is a fanatical, demanding man overtaken by a radical loneliness that causes him to lose all belief in reality. In response, he demands the impossible of the people around him. He tests the limits of all social contracts as if to prove their ultimate lack of meaning. He attacks the things which give society coherence and life meaning – government, law, culture, friendship, faith, loyalty, marriage and love. He is a figure of violent, catastrophic revolt.

He is a strain of political virus that cannot be killed

Since Caligula is ruler, his pain and confusion becomes manifest as horror in the lives of his citizens. As in the kings of Shakespeare, the convulsions of the leader are felt by the body politic. Resurrected by Camus in the darkest years of the twentieth century, Caligula serves as a kind of monstrous stand-in for the figure of the modern dictator. At the opera’s close, after Caligula has been clubbed to death by a mob, he screams, "I’M STILL ALIVE." It’s a warning and a reminder that bloated Caligula-figures are all too familiar in the despots and tyrants of modern history. He is a strain of political virus that cannot be killed – a frightening representation of what happens when power becomes absolute and when one man’s fears and fantasies dominate an entire society.

One task of theatre is to take the audience closer to things which would be intolerable in everyday life and to offer a "safe" experience of trauma. Listening to Caligula, we intimately know a nightmare of a man. Glanert’s haunting and visceral music lets us experience the chemistry of Caligula’s brain, to feel his heart beating, to know the trills and jangles of his nerves, his seizures, and flushes, the rise and fall of his breath, the voices in his head. We get close to someone who would otherwise terrify us and destroy us. As Glanert writes, "We understand him because we all have the capacity to become such a monster." We feel his violent loneliness, his despair, his terrifying intelligence. We know his appetite, his fury, what drives him. He is a torn figure – madman, clown, psychotic, politician, supreme leader. He behaves like a beast, but his decisions are entirely rational, like a scientist conducting an experiment or a poet sounding the limits of thought.

One task of theatre is to take the audience closer to things which would be intolerable in everyday life and to offer a "safe" experience of trauma. Listening to Caligula, we intimately know a nightmare of a man. Glanert’s haunting and visceral music lets us experience the chemistry of Caligula’s brain, to feel his heart beating, to know the trills and jangles of his nerves, his seizures, and flushes, the rise and fall of his breath, the voices in his head. We get close to someone who would otherwise terrify us and destroy us. As Glanert writes, "We understand him because we all have the capacity to become such a monster." We feel his violent loneliness, his despair, his terrifying intelligence. We know his appetite, his fury, what drives him. He is a torn figure – madman, clown, psychotic, politician, supreme leader. He behaves like a beast, but his decisions are entirely rational, like a scientist conducting an experiment or a poet sounding the limits of thought.

Caligula is also a theatrical creature: we watch him playing his part and manipulating the spectacle around him. Suetonius writes that Caligula was "an eager spectator of torture" and a passionate devotee of the theatrical arts:

"He was so enraptured by his delight in song and dance that, at public performances, he could not help chanting along with the tragic actor as he delivered his lines, or freely mimicking his gestures, by way of praise or correction. Indeed, on the very day of his death, it seems, he commanded an all-night performance in order to take advantage of the licence it allowed, and make his first stage appearance. He even danced at night on occasions, and once summoned three senators of consular rank to the palace at midnight, seating them on a platform when they arrived half-dead with fear, then suddenly bursting forth, clad in a cloak and an ankle-length tunic, in a clatter of clogs, to the din of flutes, danced and sang, and vanished again."

Caligula in rehearsal

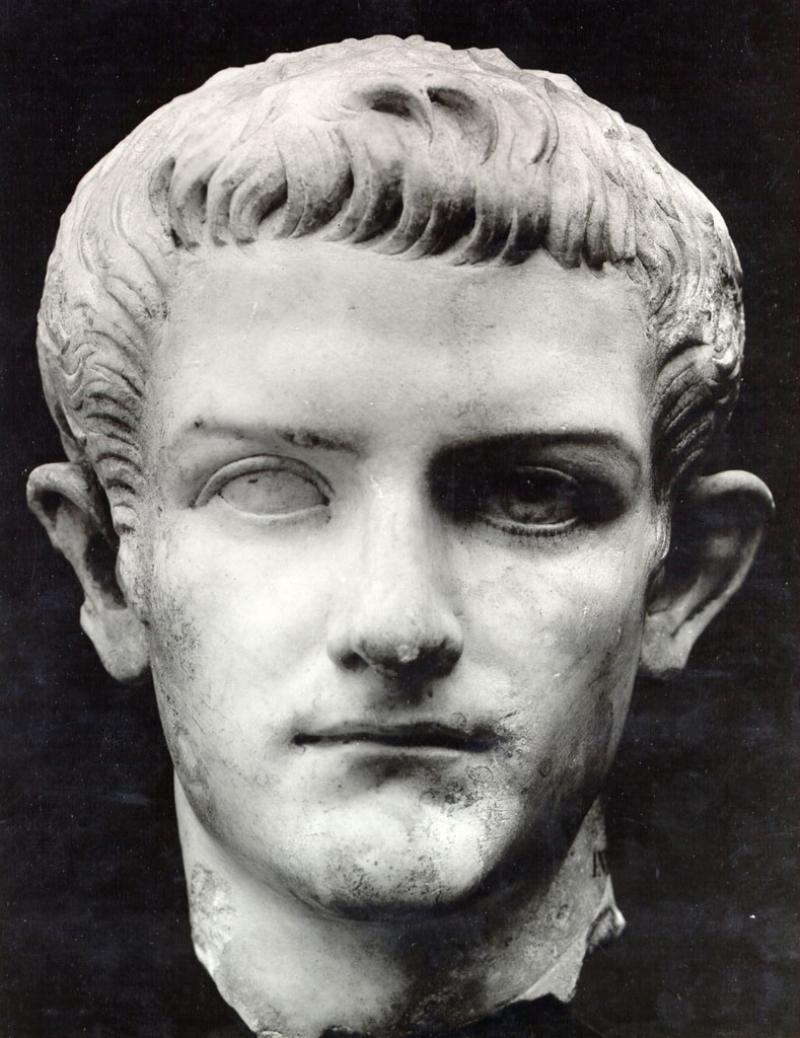

Suetonius also reports that Caligula "deliberately made himself appear more uncouth by practising a whole range of fearsome and terrifying expressions in front of the mirror". The descent of his state into political madness is accompanied by increasingly grotesque theatrical displays. Caligula dresses as Venus. He forces his populace to worship him and to dance obscene dances. His society slips into a kind of fevered pantomime – a nightmarish frenzy, the spasms of the death drive.

Every act and utterance of Caligula’s becomes public in the stadium. It becomes his echo chamber

Framed by the fantastic Roman kitsch of Frank Matcham’s London Coliseum auditorium, our Caligula rules over and inhabits an imagined, corrupt modern state. A slice of a modern sport’s stadium dominates the Coliseum stage. It might be simultaneously a place in Caligula’s psyche and the polis he returns to at the beginning of the opera, covered in mud and filth after three days in the wilderness. A lonely man – in this case the most powerful man in the society – sitting alone in a stadium is especially haunting. It’s from this image that the games and charades, the violence and the eroticism, the excess and the sorrow of the staging grows. Stadiums are central to the idea of nationhood – as the various building projects for the Olympics show – but they can also be co-opted by the forces of state terror. The Estadio Nacional de Chile became a prison camp after Pinochet’s 1973 coup d’état. Whether ancient or modern, there is a compact between state power and these sites of mass public gathering. They contain and express a shadow side of power. The stadium activates the question of audience, the crowd’s relation to power. Every act and utterance of Caligula’s becomes public in the stadium. It becomes his echo chamber.

Watching Caligula, we see a society in the thrall of one dangerous man. We watch him strut and preen on the stage as he turns his dreams into his society’s nightmares. His populace become spectators, corpses and bit players in the obscene spectacle of his tyranny. At the centre of this sick state, he sits in an empty stadium – "alone with his corpses" – staring into a mirror. The circle of glass in front of his face looks like a hole, the void of "nothing" which he pits himself against, or the silver moon which haunts his insomnia. He turns society into a vast, monstrous reflection of his own emptiness, his psychosis. Searching for a way out of this narcissistic deadlock, Camus wrote in his 1945 notebook, "The absurd is tragic man before a looking glass (Caligula). He is thus not alone. There is the need for satisfaction or self-indulgence. Now, we must abolish the glass." The task remains.

- English National Opera's production of Caligula is at the Coliseum in repertory on 28 and 31 May, 7, 9 and 14 June

Explore topics

Share this article

more Opera

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Add comment