theartsdesk at the Presteigne Festival of Music and the Arts | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Presteigne Festival of Music and the Arts

theartsdesk at the Presteigne Festival of Music and the Arts

Pocket Welsh town celebrates a range of new, beautiful, well-made works

The Presteigne Festival, which has just ended after a packed long weekend of events of various shapes and sizes, is a music fest with a profile very much its own. Presteigne is one of those enchanting pocket county towns that proliferate along the Welsh borders (Monmouth, Montgomery and Denbigh are others): towns whose municipal status seems to belong in some child’s picture book, and is in fact a thing of the distant past.

Even Presteigne’s county – Radnorshire – is no more, long since swallowed up by the huge, Celtic-sounding, but geographically meaningless Powys, then regurgitated as one of its regions. Radnor as a name survives notably in the majestic range of hills that rears up a few miles to the west of the former county town, and in a couple of nearby villages one of which (Old Radnor) has practically disappeared altogether, while the other (New Radnor) is not new at all but a gridded medieval village, itself once the county town, now all but deserted. The festival, by contrast, though 28 years old, is far from bygone and anything but deserted.

George Vass, its artistic director, chief conductor and all-round animateur, has never been content with the kind of safe classical fare that might be expected to attract the genteel senior citizens and rustic artists who mostly graze these remote pastures. He includes new music in quantities, and the citizens – junior as well as senior, artist and layman – come to listen to it. There is always a composer-in-residence, this year Hugh Wood; and other composers take part or turn up to hear their music played. John McCabe was giving a piano recital and talking about his music with Michael Berkeley, himself, of course, a composer. David Matthews is a regular, regularly performed.

Perhaps this isn’t quite the cutting edge of new British music. Ferneyhough, Turnage, Gerald Barry it ain't. Vass, one senses, is more interested in locating a mainstream repertoire of beautiful, well-made new works that resist the temptation to rearrange his audience’s hearing or disjoint their noses. And to a remarkable extent he succeeds, even though commissioning can be a risky business and not every goose can be a swan. I heard two of this year’s novelties, one a skilful and delectable remake by Wood of a fragmentary early song cycle of his from the 1950s, the other a post-Lloyd Webber, sub-Rutter confection by Alexander L’Estrange, 40 years Wood’s junior and raised, one might suppose, on another planet. But the same concerts also programmed strong not new modern works – in fact the L’Estrange concert was entirely post-1940. In the other concert only a Mozart concerto (to some extent) and a Schubert symphony flattered its audience’s more benign expectations.

The Wood cycle, called (self-satirically, I suspect) Beginnings, is a setting of three longish poems linked by what he calls a “similar atmosphere, to do with mystery, magic, innocence, childhood". What may actually have re-attracted him to these three poems – the anonymous “Tom O’Bedlam’s Song”, Dylan Thomas’s “Why East Wind Chills” and the “O Unicorn Among the Cedars” passage from Auden’s New Year Letter - is the sense of something beyond, questions unanswered or unanswerable, voyages into the dark forest of the mind. Their first musical concept lends itself to elaboration by a composer whose style and technique moved from the Vaughan Williams-ish neighbourhood of Fifties England through the discovery of Schoenberg, and out the other side into the dense, richly allusive neo-Romanticism we associate with Wood’s music from Scenes from Comus onwards. These songs travel that route (“Methinks it is no journey”, sings Tom O’Bedlam, but he’s mad of course), and the evolution is fascinating to trace, even though one can’t always locate the jumping off points. In fact this is the measure of Wood’s skill. Clare McCaldin sang the piece with intensity and commitment, sensitively accompanied by Vass and the excellent Presteigne Festival Orchestra.

The same concert (the festival’s finale) also included Robin Holloway’s Ode of 1980, one of his subtlest explorations of the psychology of reworking - in this case from the music of another composer, Britten's Serenade. And there was yet another kind of rehash in Thomas Gould’s performance of Mozart’s D major Violin Concerto, K 218. Gould played what Mozart wrote very nicely, if with smallish tone, which may partly explain why, for his cadenzas, he reached for an electric violin and, accompanying himself on a pre-recorded track, for several excruciating minutes reimagined himself as a busker at the Monument tube station interchange. Good for him to set up an alternative career, I suppose. Let’s hope that for his and the commuters’ sakes he doesn’t need it.

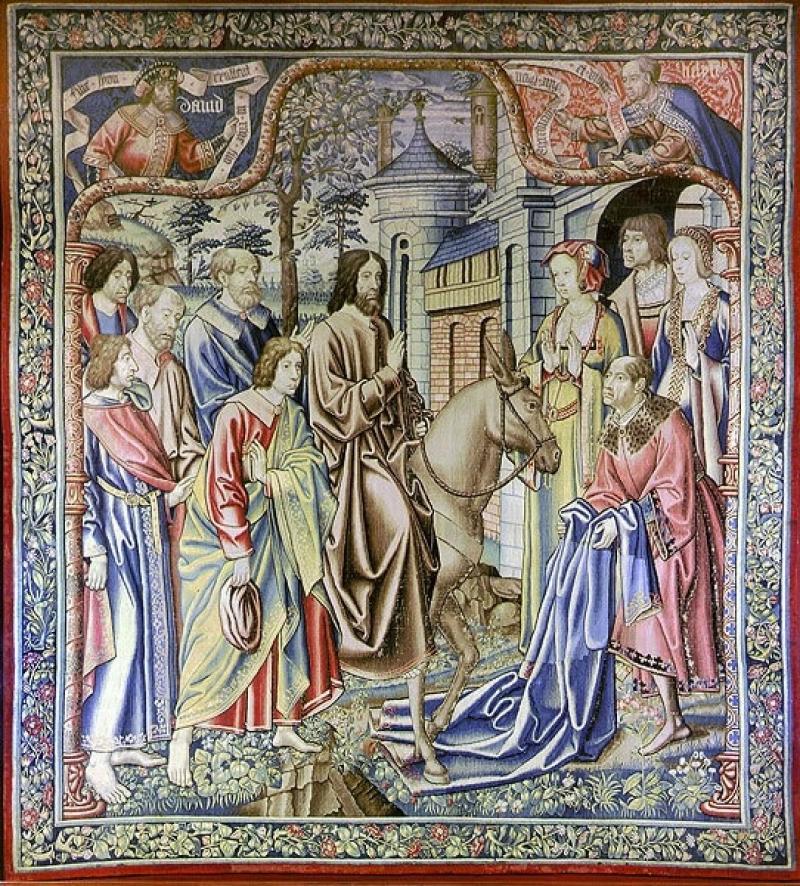

The L’Estrange concert, on Saturday, was a mixed bag in quite a different kind of way. The less said about L’Estrange’s own song cycle, And the Stones Sing, perhaps the better. Its merit was that it drew attention to one of the star items in Presteigne’s fine Parish Church, where these concerts happen: a beautiful 16th-century tapestry of Christ’s “Entry into Jerusalem”, 500 years old this year. Adey Grummet had written a series of poems celebrating the birthday, modestly lofty in style, exploring the ironies of Palm Sunday – the glory and the shame, so to speak; L’Estrange chose to set them to music that might, without too much incongruity, slot into the next edition of the Happy-Clappy Songbook. Neither McCaldin nor the Joyful Company of Singers could do anything with this. Better, though patchy, was Tarik O’Regan’s Triptych, a choral cycle that deliberately mixes an urban vibrancy with the reflective intensity of earlier choral works by this gifted composer. And we heard a series of short, gentle pieces by Arvo Pärt (of whom more next week from the Vale of Glamorgan), the Capricorn Concerto of Samuel Barber – in rather abrasive contrast – and a lovely string piece, Landscape, by Andrzej Panufnik, exquisitely played. Vass conducted everything, with aplomb and at least feigned enthusiasm. The risks, as he hinted in his platform speech at the very end, are well worth taking. I hope he’ll go on taking them.

- Discover more about the Presteigne Festival

Share this article

more Classical music

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Add comment