theartsdesk at Førdefestivalen: Music and the midnight sun | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at Førdefestivalen: Music and the midnight sun

theartsdesk at Førdefestivalen: Music and the midnight sun

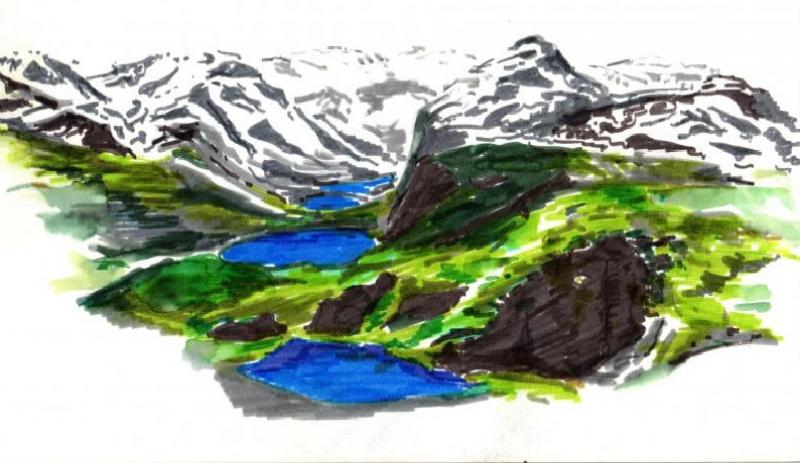

Gathering of world and folk musicians in Norway's fjord country. Plus sketches by the writer

The first thing that strikes you at 3am is the light, that strange disembodied glow of Norway’s midsummer midnight sun casting its rays over a landscape soaked in fantasy proportions – sheer glacial drops of greenstone, sweet-water fjords cutting deep into the land, the forests of spruce and pine desending from steep mountainous peaks to the meadow grasses of the valley below.

My route to Førde and its 28th annual festival of world and folk music started on a speedy cruiser, leaving on the dot at 8am from Bergen for the island of Krakhella. From there, a postal boat wove its hem through the Solund islands, the westernmost part of Norway, and set in a land-and-seascape (see gallery overleaf) upon which myths and sagas sleep and rise fitfully, scattered across a sea that flows dark and swollen towards Shetland. The archipelago’s mix of gargantuan conglomerate and greenstone is the result of millennia-old geophysical forces that were once retold as the workings of Norse gods. Now we know it to be glaciation and tectonic shift doing its work while our early human forebears were mixing ochre pigments in the caves of southern Europe, parting from the herd to leave us their tracks.

It looks like the most beautiful island on Earth

The same reddish ochre is the pigment used to pick out the rock art overlooking the sea and the sweetwaters of Høydalsfjord at Ausevik and its open-air gallery of stone-etched labyrinths, sun wheels and deer figures – often depicted heavily pregnant and with a dense inner geometry of lines, like plots on a map whose scale and purpose remains unknown. Reindeer run wild in the northern realms of this long slim land, but on Swan Island they are farmed on a diet of raw potatoes, and are quite tame.

Gliding towards the long wooden jetty of Svanøy, crystal clear waters below, verdant forests rising above to a snowline of expressive peaks, it looks like the most beautiful island on Earth. The sun is out, the air is warm and the wind is still. The intensity of light here takes the breath away. So can the midges at dusk.

The little town of Førde – a few main streets, and little roads of wooden houses straggling towards the foot of the surrounding mountains – is near the source of Førdefjorden (the Førde Ford), one of the longest in the region, some 34km from source to coast. It may be 29 degrees centigrade down here at sea level, but up there the snowline shows little sign of diminishing, the mountain peaks still thickly streaked, glistening in the daytime sun.

Førde Festival began small but has developed a world-class artist roster and strong local support and involvement – from the concerts themselves, dotted around town and in the surrounding countryside, to the closing parade and festival breakfast in the park by the river on Saturday morning, when the whole town feasts on local produce. Over its 28 years, Førde has nurtured world-class talent from across the globe with its New Talent showcases, this year from Iran, Armenia and Norway – Seckou Keita scored his first gig outside Senegal this way. The Young Musician of the Year showcase in the town’s beautiful, if lightly dilapidated Cultural School features the best young Norwegian players, including young Hardanger fiddler Bjørn Kåre Odde, who played for us at a private house gathering at Svanøy mansion on Swan Island.

Whether on stage or in the bar after hours, the sound of Nordic fiddle, nyckelharpa and the magically resonant sympathetic strings of the Hardanger fiddle predominate; this is the Norwegian sound that travels inwards and stays with you the longest. This year, visiting headliners included Catrin Finch and Seckou Keita, Natacha Atlas, Toto La Momposina, and Janusz Prusinowski with the famed pianist Janusz Olejniczak, who performed the music in Polanski’s film, The Pianist.

Whether on stage or in the bar after hours, the sound of Nordic fiddle, nyckelharpa and the magically resonant sympathetic strings of the Hardanger fiddle predominate; this is the Norwegian sound that travels inwards and stays with you the longest. This year, visiting headliners included Catrin Finch and Seckou Keita, Natacha Atlas, Toto La Momposina, and Janusz Prusinowski with the famed pianist Janusz Olejniczak, who performed the music in Polanski’s film, The Pianist.

Finch and Keita remain warm, sublime and intimate in their conversation between harp and kora, while Natacha Atlas brought an acoustic, Arabic jazz vibe to the main stage. Toto La Momposina, who makes a rare UK visit to Womad at the end of this month, is still at 75 an exultantly powerful singer and stage presence, that mighty voice rising up and out to tear the fabric of the air for her expansive set in the town’s park, by a river swollen with snowmelt. Janusz Prusinowski fused avant-folk country mazurkas and polkas from deep into the interior of rural Poland – still a world or three apart from the cities – while pianist Olejniczak showed how Chopin brought this rural culture, surface-simple but richly ornamented, to the outside world.

It was an example of the 2015 festival’s overriding theme, of connections – between songs, between dances, between strings, between voices. Vocal Connexions (pictured above), directed by Grete Pedersen and featuring Polish, Breton, Bulgarian and Finnish singers, including Bulgaria’s Gergana Dimitrova, Annie Ebrel from Brittany and Sami singer Ulla Pirttijärvi, was an intricately devised drama of voices, recomposing the basic elements of human expression into single-syllable utterances and sudden expulsions merging with thrilling, almost supernaturally potent part-singing and polyphony. All this before a small congregation in Førde church. It made you realise that, yes, in the beginning was the word – and the word was sung. What we heard was the sound of women’s voices cascading in quarter tones down through the millennia while the rest of us sat silently on our pews, apes agape…

Likewise the audaciously impressive stagecraft and animated projections of The Seasons (pictured left). This evocation of Norway’s epic weather by dance and music group Villniss proved to be a visual and musical spectacular for which the stage business involved a circle of fans and featherlight bolts of cloth, rising and falling from rafters to stage floor in a brilliant example of airborne choreography, evoking the changing spirits of the Norwegian seasons.

Likewise the audaciously impressive stagecraft and animated projections of The Seasons (pictured left). This evocation of Norway’s epic weather by dance and music group Villniss proved to be a visual and musical spectacular for which the stage business involved a circle of fans and featherlight bolts of cloth, rising and falling from rafters to stage floor in a brilliant example of airborne choreography, evoking the changing spirits of the Norwegian seasons.

Being midsummer, the out-of-town, up-in-the-hills concerts left the deepest impressions. This was most spectacularly true for Nomadic Voices, on the 750m peak of Hafstadfjellet, overlooking Førde, where the small crowd that had made it to the top watched and snapped photos as two paragliders stepped off into the high air just as the sound of Mongolian throat singers threaded with the dark matter of a polyphonic Sardinian chorale began to fill the mountain air.

Over the next hour or so, the two sets of voices merged and divided and rose over the peaks just as the paragliders’ man-made wings rose and fell with the thermals, and those nomadic voices circulating over the verdant river valley far below.

Further down the valley, and on the last morning of the festival, we settled at the foot of majestic Big Horse mountain south-east of Førde, in the grounds of Rytne Farm in Bygstad. The long wooden building has a meadow roof, lined with the bark of silver birch, and parts of the farm house date from the 15th century. Fortunate visitors enjoy the use of an open-air sauna dug into the lip of the hill overlooking a ludicrously bucolic vista of rolling farmland, twisting rivers, forested valleys and dramatic peaks.

Here, Sami singer Ulla Pirttijärvi and her trio Ulda performed new and traditional joiks from the far north of the planet. Hers is one of the last surviving nomadic cultures of Europe, with very strong folkloric and music traditions threading even through the impermeable fabrics of the modern world, and she wears that legacy with pride, power and purpose. Her costume is decorated with totems of sympathetic Sami powers akin to those sympathetic strings that make the Hardanger resonate – a butterfly over the heart, a silver pendant of a bird, a palaeolithic sun wheel of the kind we saw etched into the rock at Ausevik, and on her back the figure of a shaman with a drum, for sound and divination. Ulla, too, holds a drum.

Here, Sami singer Ulla Pirttijärvi and her trio Ulda performed new and traditional joiks from the far north of the planet. Hers is one of the last surviving nomadic cultures of Europe, with very strong folkloric and music traditions threading even through the impermeable fabrics of the modern world, and she wears that legacy with pride, power and purpose. Her costume is decorated with totems of sympathetic Sami powers akin to those sympathetic strings that make the Hardanger resonate – a butterfly over the heart, a silver pendant of a bird, a palaeolithic sun wheel of the kind we saw etched into the rock at Ausevik, and on her back the figure of a shaman with a drum, for sound and divination. Ulla, too, holds a drum.

She performed in front of a small wooden pavilion by a pond, beside her a waterfall splashing over the fern-clad rocks. She is a small woman, and suddenly she and all of us seemed tiny and insignificant against the array of natural forces gathered around us. Her voice and style is a fabric strong and soft enough to get beneath the skin and stay there, and hearing her sing a beautiful joik for her newborn daughter, written more than 20 years ago now, I found myself moved to tears, as if a faultline had opened up and released what usually stays hidden inside.

Why is that? How does music like this do something like that? Well, perhaps there’s this: the marine point of close contact from a distance. And that’s what we love about songs, and singers like these. They’re what lies beyond the naming of parts. You can’t bottle that kind of spirit. You can nurture it though, as Førde does so well, which is why we are here, and why Ulla is here to sing for us, that thread between us resonating like those sympathetic strings of the Hardanger.

You’re not going to get an app for that kind of experience; you’ve got to get up and get here for yourself.

- Tim Cumming's new collection, Rebel Angels in the Mind Shop, is published by Pitt Street Poetry, Sydney, Australia

- More information about Førdefestivalen

Overleaf: browse a gallery of sketches of Førde by Tim Cumming

Click on the thumbnails to enlarge

more New music

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Ellie Goulding, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall review - a mellow evening of strings and song

Replacing dance beats with orchestral sounds gives the music a whole new feel

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: A Certain Ratio - It All Comes Down to This

Veteran Mancunians undergo a further re-assessment and reinvention

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

Album: Maggie Rogers - Don't Forget Me

Rogers continues her knack for capturing natural moments, embracing a more live sound

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

theartsdesk at Tallinn Music Week - art-pop, accordions and a perfect techno hideaway

A revived sense of civilisation thanks to dazzlingly diverse programming

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Album: Lizz Wright - Shadow

Brilliant album from superlative vocalist

Add comment