Betroffenheit, Crystal Pite & Jonathon Young, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Betroffenheit, Crystal Pite & Jonathon Young, Sadler's Wells

Betroffenheit, Crystal Pite & Jonathon Young, Sadler's Wells

Astonishing, unclassifiable work of dance theatre about an unrepresentable subject

Where does my voice come from? Whose is my body? It’s apt that these questions run deep through a work that was created jointly by an actor, Jonathon Young, and a choreographer, Crystal Pite.

The opening scene already disorients and unsettles. In a darkened warehouse room, an electric cable snakes across the floor; another rises like a cobra up the wall, in search of its socket. Powered up, the room itself seems to speak to Young, who hunches in a corner as the lights flash in sync with a voiceover of repeated, fragmented phrases: "Oh my God", "There’s no information", "The system is failing".

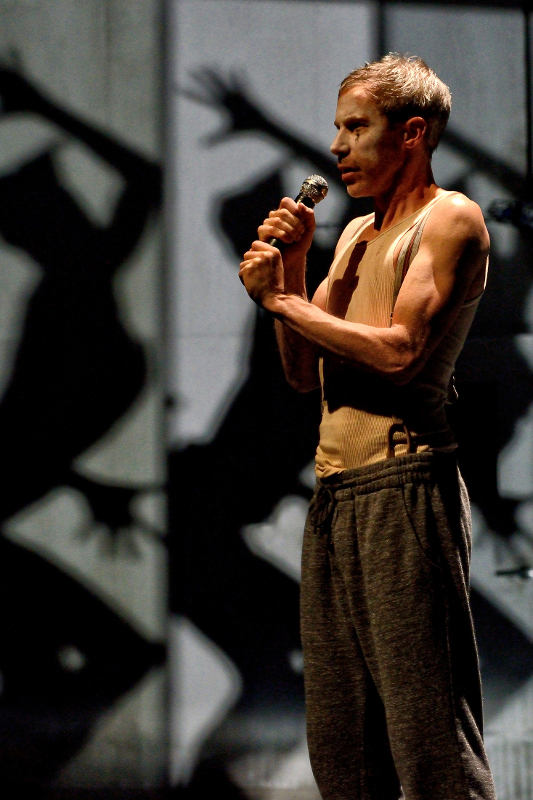

Young switches on a black-box speaker, and it speaks back in his voice. Dancer Jermaine Spivey sidles in like a shadow against the wall, his limbs twitching in sync with the speaker’s voice. When he turns to face Young, we see that he is lipsyncing too. They synchronise their stances. From here on through to the end, Young and Spivey now seem to be the same person, one whose voice appears in various guises too: live, recorded, lipsynched, located, disembodied. No wonder Young (pictured right) is having trouble holding himself together: he is all over the place.

Young switches on a black-box speaker, and it speaks back in his voice. Dancer Jermaine Spivey sidles in like a shadow against the wall, his limbs twitching in sync with the speaker’s voice. When he turns to face Young, we see that he is lipsyncing too. They synchronise their stances. From here on through to the end, Young and Spivey now seem to be the same person, one whose voice appears in various guises too: live, recorded, lipsynched, located, disembodied. No wonder Young (pictured right) is having trouble holding himself together: he is all over the place.

But he can’t escape: the room is not only where he is, it’s who he is. Instead, he escapes into a drugged, hallucinatory fantasy; he “gets out of it”. The room is invaded by nightmarish cabaret entertainers with painted faces (pictured below) – a grinning, hunched tap dancer, pink plumed showgirls, a glitzy salsa couple – and he and his other self Spivey take the stage as a bantering double-act, an imaginary audience guffawing at their every quip. Until the inevitable come-down – Young appears as a puppet version of himself, a diminished man – and then the inevitable crash, as he returns to the bare room, his sparkling fantasy figures slumped stoned around him.

Considering he had no dance training before creating this piece, Young is an astonishingly accomplished mover, holding his own in the skilfully choreographed sections with Pite’s dancers. His performance as an actor, neither sentimental nor manipulative, is wrenchingly moving, almost unbearably painful – and still, his character has more to suffer. His “system” fails: the walls of the room move away, the stage is swept by a billowing sheet of darkness, and Young collapses, the dancers clustering around his body and gesticulating to panicked voice-overs like characters in an ER drama, desperately trying to revive a critical casualty (main image).

Pite’s direction throughout this first act has been commandingly cinematic: dense with incident but with fluent scene cuts, tightly synchronised soundtrack, tracked focus, swift pacing and high tension. For the shorter second act, she shifts to a less dramatic, more dance-based mode that nonetheless – like a series of softer aftershocks – often echoes images from Act One. On a clear stage now, the dancers run ragged like the fugitive figures that we’d glimpsed before in flashes of torchlight. They replay the whole ER section as choreography, only with no voiceover and no supine patient to attend, just the motion of their own bodies. The underlying patterns of Act One are still here – in a duet of constantly collapsing support, in solos which trip up their own performers – but they feel less locked down, less tethered by trauma’s obsessive retelling of its own story.

Does this allow Young to resolve his crisis? That would be a facile, Hollywood ending. Instead Betroffenheit offers a more ambiguous loosening of ties, an opening of space – not a resolution as such, but a change of sorts. The room is still inside him, but Young is no longer inside the room.

Betroffenheit is an astonishing accomplishment. It is intense, raw and often itself traumatic; yet even as we feel its force, we notice how very finely crafted, paced and performed it is. Young’s harrowed soul is of course central to its achievement, but this is fundamentally an ensemble piece. Pite’s five dancers are marvellously versatile, whether moving to the rhythms of sputtered speech, shuddering as if in stop-motion film, or dancing full-out through dense sequences of reckless skids, skewed turns and limb-wrangling tumbles. Full credit, too, to the design team, for their inventive and effective use of light, costume, sound and set. But it’s the piece itself that grips, its imaginative treatment of a subject as intractable, as unrepresentable as trauma itself. Instead of telling the story of a trauma, it stages its patterns, follows its arcs. When you leave the theatre, its aftershocks stay with you.

- Betroffenheit is on at Sadler's Wells until 12 April. It will be screened on BBC Four, date as yet unconfirmed

- Read more dance reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

more Dance

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

Carmen, English National Ballet review - lots of energy, even violence, but nothing new to say

Johan Inger's take on Carmen tries but fails to make a point about male violence

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

WAKE, National Stadium, Dublin review - a rainbow river of dance, song, and so much else

THISISPOPBABY serves up a joyous tapestry of Ireland contemporary and traditional

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

Swan Lake, Royal Ballet review - grand, eloquent, superb

Liam Scarlett's fine refashioning returns for a third season, and looks better than ever

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

First Person: Ten Years On - Flamenco guitarist Paco Peña pays tribute to his friend, the late, great Paco de Lucía

On the 10th anniversary of his death, memories of the prodigious musician who broadened the reach of flamenco into jazz and beyond

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Dance for Ukraine Gala, London Palladium review - a second rich helping of international dancers

Ivan Putrov's latest gala was a satisfying mix of stars and young hopefuls

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Nelken: A Piece by Pina Bausch, Sadler's Wells review - welcome return for an indelible classic

A new generation of gifted performers for us to get to know

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

Dark With Excessive Bright, Royal Ballet review - a close encounter with dancers stripped bare

The Royal's Festival of New Choreography launches with an unforgettable walk in the dark

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

La Strada, Sadler's Wells review - a long and bumpy road

Even the exceptional talents of Alina Cojocaru can't save dance adaptation of Fellini film

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

First Person: pioneering juggler Sean Gandini reflects on how the spirit of Pina Bausch has infiltrated his work

As Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch's 'Nelken' comes to Sadler’s Wells, a tribute from across the art forms

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Manon, Royal Ballet review - a glorious half-century revival of a modern classic

Fifty years on, Kenneth MacMillan's crash-and-burn anti-heroine is riding high

Add comment