Perspectives: Sergeant on Spike, ITV1 | reviews, news & interviews

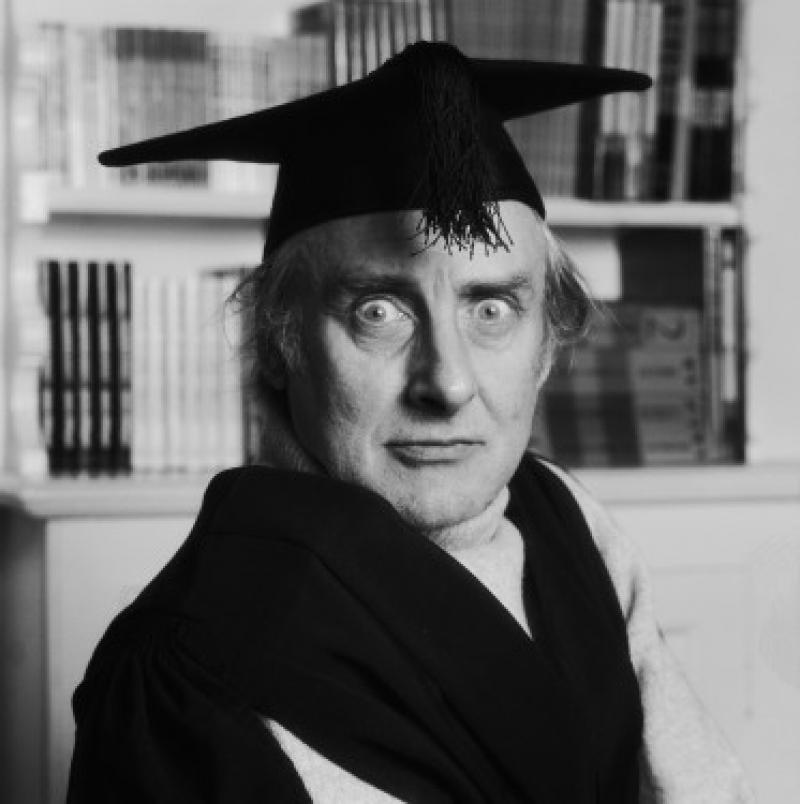

Perspectives: Sergeant on Spike, ITV1

Perspectives: Sergeant on Spike, ITV1

Shallow documentary on the late Goon leaves grave stones unturned

As a prelude to last night’s John Sergeant Perspectives doco, I made a note of the four things I thought I knew about Spike Milligan.

I assumed that Sergeant would tell me more; but it soon transpired that his plan was not so much to offer a straightforward biography as to present a twofold thesis: how Spike Milligan had made him – Sergeant – the comedian he is today (“today” being, presumably, some time around the mid-Sixties) and how he – Milligan – had fundamentally altered the nature of British comedy in the decades following the Second World War. Even Sergeant didn’t appear to think the first part deserved that much discussion.

Perhaps, aptly enough, the programme had originally been commissioned for radio

The second aspect was the real meat, and after tripping quickly through the salient points of Milligan’s childhood (the weird and wonderful Indian upbringing, the military-entertainer parents) we returned to Blighty with Spike and family, just in time for WWII, whereupon Gunner Milligan was promptly mobilised to the superbly Goonish location of Bexhill, in Surrey: “We arrived into Bexhill-on-Sea,” Spike wrote later, in his memoirs, “where I got off. It wasn’t easy: the train didn’t stop there.” In true Dad’s Army fashion, the young Milligan found the enticingly shallow coastline fortified – with scaffolding poles.

But Spike’s war warmed up, slowly but surely, ending only when he was wounded at Monte Cassino. You’d have thought that near-death in battle might be formative in the psyche of a would-be comedian; but no attempt was made to explore it.

Post war, Milligan moved back to London, where he found himself living on the top floor of Grafton’s pub – “the Cavern of comedy” – along with a monkey (the monkey got the bigger room). There he was introduced by a fellow soldier to Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers and Michael Bentine, and Grafton’s became ground zero for an accidental and particularly odd form of national psychological recovery: “four men in a pub” performing cathartic – and seemingly slightly hysterical – comedy.

With its memorably surreal antics, oddball characters and neatly parodical storylines, the Goon Show was perfect for radio. There is little evidence that it was hilarious – let alone more hilarious – when seen live; but that noted comedic authority Esther Rantzen said that it was, with particular reference to its ground-breaking sound effects (which she then proceeded to demonstrate, none-too-brilliantly, with an umbrella).

What was evident was that Milligan, the chief scripter of the show – who quickly graduated from living with the monkey to renting with Eric Sykes and Galton & Simpson – “really was a comic genius". Equally obvious, with Milligan responsible for knocking out 25 Goon Shows a year, this was going to take its toll. Milligan wrote a lot – and he wrote alone.

He retired from the Goon Show in 1960 (I'm not compressing much here, by the way) and notwithstanding his actor-writer credits on the 11-minute Running, Jumping & Standing Still (which bagged an Oscar nomination and got Richard Lester the job of directing the Beatles’ first feature) it took a decade for Milligan to give in to the inevitability of television – only to find he was too late. Monty Python had got in on the game, and there was, Michael Palin says ruefully, a certain… “atmosphere” between them. It seems Milligan even went so far as to accuse the Pythons of plagiarism.

“Spike had no need to be charming,” noted a former colleague, playwright John Antrobus. “He was raw… like an undisciplined child.” In fact, Spike and his comedy shared many childlike qualities. Through stubbornly professional in his approach to joke-making, Milligan was dismissive of his adult audience – “a love/hate relationship: he needed them, and he hated that he needed them” - and, as with Roald Dahl, he preferred the company of children and animals. Like Dahl, though, there was a dark side to his childish sense of fun, from which children themselves were not necessarily protected. Milligan one day told the Graftons’ son that he wouldn’t be talking to him any more, as he was now too tall. He wasn't joking.

Spike had a love/hate relationship with everyone, in fact, including Norma Farnes, his former secretary and now literary executor. Through all of his personal turmoils, Farnes was his rock. She loved him dearly, but “if I’d been ‘in love’ with him he’d have torn me to pieces within the first three months… Can you imagine living with Spike Milligan? It must have been a nightmare.”

Indeed. We were offered one remark from Noel Fielding about how the incessant search for comedy drove Milligan over his own edge; Farnes told us how he often locked himself in his room when “the Black Dog had him”; and Milligan’s brother, Desmond, said, “None of us was quite as mad as he was,” – albeit apparently in a different context. And that, so far as Milligan's debilitating depression and lifelong personal chaos was concerned, was that.

In fact, the whole programme was rather superficial: as if Sergeant had been forced to work without key material, or just on a very tight budget, with very little time. Where was the fire? The ostensible point of the programme, the 10th anniversary of Milligan’s death (26 February), had certainly been well and truly missed. Perhaps, aptly enough, the programme had originally been commissioned for radio.

The easy route of going backwards to Spike through the comedy family tree didn’t work either, not least because between them Palin, Fielding and Eddie Izzard hardly represent the majority of what’s been seen in British comedy over the last 40 to 50 years – and something really wasn’t gained by watching Izzard try to show us the anatomy of surrealist gags. (Maybe the problem is simply with surrealism itself. At one point Sergeant showed us a photograph of Man Ray’s iron: “it forced you to stop and think,” he said, weightily. Did it? Of what?)

The easy route of going backwards to Spike through the comedy family tree didn’t work either, not least because between them Palin, Fielding and Eddie Izzard hardly represent the majority of what’s been seen in British comedy over the last 40 to 50 years – and something really wasn’t gained by watching Izzard try to show us the anatomy of surrealist gags. (Maybe the problem is simply with surrealism itself. At one point Sergeant showed us a photograph of Man Ray’s iron: “it forced you to stop and think,” he said, weightily. Did it? Of what?)

Sergeant himself, it must be said, was not particularly exhilarating. If he was overwhelmed with enthusiasm for his subject, it didn’t show (the voiceover didn’t even sound like his, though no-one else was credited for it). And several of his interview assistants didn’t look like they'd drunk the Kool-Aid, either: “So we have a little bit of history being made right here,” says Sergeant to Dave the Grafton's publican, showing him a photo of the loft in his pub. “Along with the beer-crates,” adds Dave.

They had a good idea for an ending, at least: an experiment to discover if the Goon Show is still funny to the children of today. Alas, though, for Sergeant’s less-than-unbiased thesis – and contrary to guileless protestations – with the exception of the silly voices and whoopee cushion sound-effects, the well-mannered, primary-age kiddies in question remained visibly unmoved, and not a little perplexed. One sympathises.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more TV

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Prisoner, BBC Four review - jailhouse rocked by drugs, violence and racism

Sofie Gråbøl joins a powerful cast in bruising Danish drama

Prisoner, BBC Four review - jailhouse rocked by drugs, violence and racism

Sofie Gråbøl joins a powerful cast in bruising Danish drama

Drive to Survive, Season 6, Netflix review - F1 documentary overtaken by events

Real-life dramas in the paddock were too late to make the cut

Drive to Survive, Season 6, Netflix review - F1 documentary overtaken by events

Real-life dramas in the paddock were too late to make the cut

Comments

I wonder where Mr Sergeant

In reply to Simon H, I would